Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael Alexander‘What if every student had a job?’ Atlanta takes up the Cristo Rey challenge

By ANDREW NELSON and NICHOLE GOLDEN, Staff Writers | Published September 18, 2014

Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School opened its doors in August with some 160 students in the inaugural freshman class of this Atlanta school. It’s the first Catholic high school to open in the center of the city since the 1970s when St. Joseph High School closed. Marist School moved from its downtown campus beside Sacred Heart Basilica in the 1960s to the suburbs.

The West Peachtree Street school offers a college prep curriculum for students from financially strapped families. What is unique is how it does this: one day a week, on a rotating schedule, students are at work in 41 Atlanta businesses earning money to subsidize their education.

The Georgia Bulletin will be running a three-part series introducing the concept of the school and focusing on two of its students, followed by an in-depth look at their work-study program, and ending with a school year wrap-up as students and staff review the first year.

ATLANTA—Posters of favorite video games cover the bulletin boards. Academic medals earned in middle school for mastering high school physical science and algebra hang nearby, along with a dagger bought at a medieval fair. Sean McNeal’s desk, surrounded by these conversation pieces, is where he works to make sense of paragraphs of Latin homework describing Helen of Troy.

Sean hopes the unfamiliar language, in addition to his twice-a-day math and English classes, put him on the track for college and then a career in law enforcement.

“I’d have to struggle less,” said the teen about his new hopes for the future. “I come from a family who never finished high school or college. They’ve had a rough time.”

Struggle is what many of the 160 students at the new Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School have always known. The college prep school serves financially strapped families. Most of them bring home half of what is the average income for metro Atlanta households, about $28,800.

Sean McNeal, center, listens to his English teacher, Emily Bird, as the class reads and analyzes a short story by author Karen Russell. Photo By Michael Alexander

The challenges facing students aren’t just in the classroom. Simply getting to the Midtown school is a sacrifice.

Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez and her father, Manuel, leave their Lawrenceville home at 5:50 a.m. each weekday. She then meets up with a classmate before heading to the West Peachtree Street high school.

After school, the girls ride MARTA to Doraville, where the classmate’s mom picks them up. Bethy admits the commute is “pretty complicated,” but attending school in the heart of Atlanta is teaching her independence.

It’s a year of new things all around for her. The freshman is attending a school new to the community, making friends from throughout metro Atlanta, and has her first job through the school’s corporate work-study program.

“I love it so far. It’s very different from other schools,” said Bethy about the freshman experience.

With a motto of “The School That Works,” Cristo Rey schools aim to propel these students to college to shatter ceilings in their lives. The national network of 28 schools has a track record of success. It has a college acceptance rate of 100 percent, and 90 percent of its graduates go on to enroll.

These schools give ambitious students a chance at a college prep curriculum they couldn’t afford otherwise.

“Education is a fundamental right. God is intelligent, God is creative, God is loving, God is forgiving,” said principal Jesuit Father Jim Van Dyke. “To deny any human person to be all those things is a sin. A lot of our kids have been denied those opportunities.”

“Proof that it is God’s work”

Jesuit Father John Foley founded the original Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in southwest Chicago in 1996. He is now the chief mission officer of the Cristo Rey Network of schools, which now includes 28 high schools in 18 states.

A Chicago native, Father Foley spent years teaching in Peru. Upon returning home, Father Foley and two other Jesuits were charged with opening a high school for underserved neighborhoods and populations, especially Hispanic students.

A challenge was how to pay for this program, without burdening parents with more bills and putting the school out of reach.

“What if every student had a job?” asked a consultant after weeks of intense study.

“We had no idea that it was such a powerful educational experience,” said Father Foley about what he called a grace-filled moment.

Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez, right, and Anyea Hampton look over a word problem together during their fourth-period math class. Photo By Michael Alexander

At Cristo Rey schools, four days a week students learn like typical high-schoolers. One day a week, they work as paid interns doing clerical tasks in Atlanta firms, some of them well known, like Coca-Cola and Delta Airlines. The money earned at work subsidizes the school tuition.

The fact that the Cristo Rey concept has spread nationwide with 9,000 high school students enrolled in 2014 is “proof that it is God’s work,” said Father Foley.

Atlanta Catholic leaders in 2011 began exploring starting a Cristo Rey school. In 2013, Deacon Bill Garrett started as the school president. Deacon Garrett, who serves at All Saints Church, in Dunwoody, admits he didn’t see the vision right away.

“Frankly, I wasn’t convinced the concept would work,” he said.

He didn’t understand why businesses would pay teens to work in their office. But as he looked into it and learned from his daughter, an administrator at a Cristo Rey school in New York City, his skepticism changed.

“I called around and found it works,” said Deacon Garrett, the former president of the Mercy Care Foundation, a medical outreach program to the homeless and others without insurance. He learned businesses benefit from the students and invest in their education.

The school raised the Atlanta profile of the Jesuits, officially known as the Society of Jesus. The religious order, well known for its ministry in education, in the past focused its work here on giving retreats at Ignatius House, a place for contemplation along the banks of the Chattahoochee River. This new ministry instead puts their work in the center of the city. Three Jesuit provinces of New England, New York and Maryland are collaborating on the Atlanta school. Two Jesuit priests serve there.

“We are called by the church to be on the frontiers,” said Father Van Dyke.

The son of a public school teacher, he was on track to be the president of a Jesuit school in New York City, but came here to lead the school. At a recent lunch, he undid the top button of his black shirt and removed the telltale white collar. He ordered a lunch of a hamburger, fries and un-sweet tea. A man nearby interrupted him to congratulate the principal on the new school. A father of a Georgetown University graduate and a Mexican-American, the man said he’d heard of the good work of Cristo Rey schools to help Latino students.

Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez, third from the left, joins some of her classmates during morning Mass at the school. Jesuit Father James Van Dyke, far right, principal of Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School, is the liturgy’s main celebrant. Photo By Michael Alexander

The goal of a Jesuit education is to teach students to “converse rather than shout, to listen rather than orate,” said Father Van Dyke.

A college degree is the best way to lift a person from poverty, to get people into a good paying job where they can earn money to raise a family, set aside some for retirement, and live a decent life, he said. Education is a way to break through political logjams on how to combat poverty, he said.

“We do aim to educate the whole person, body, heart and soul. It is also not just about today. We are worried about the students five years out, 10 years out, 20 years out” and eventually “to be at home with God,” he said.

Father Van Dyke has a divinity degree, in addition to a master’s degree in a “great books” program. He said the school’s commitment is to make sure “100 percent of our graduates will be 100 percent college ready.”

Achieving the goal will require students to study Latin.

“You study Latin not to order off the menu. Latin is for literacy,” he said.

Also, the thought is it will grab the eye of admissions counselors as the students in the class of 2018 apply to college.

Deacon Garrett and Father Van Dyke spent much of 2013 at poorer parishes to pitch the idea of a college prep program to families and students. At the same time, at more well-to-do parishes they lobbied Catholic corporate leaders to sponsor a student. The income from the work-study covers about 42 percent of the school’s budget, or nearly $1.2 million. Forty-one companies stepped up to hire these students.

Cristo Rey staff members were moved by the strong interest shown in the program. Parents trusted something untried in Atlanta.

“We had nothing but an office building. Parents were signing up. There was a tremendous amount of faith,” which encouraged staff to deliver on the promise, said Deacon Garrett.

School leaders were surprised as the inaugural class enrolled. Other Cristo Rey programs had about 70 percent of admitted students accepting a place at the school. Here it was closer to 90 percent.

The Midtown neighborhood office building, which housed the administrative offices of the Archdiocese of Atlanta for many years, has been converted to a 39,000-square-foot school with 16 classrooms. There is a staff of 24, with 10 teachers.

Students come from 77 feeder schools, nearly half from public schools. They live as far away as Stockbridge, Rockdale County, Duluth and Douglasville. Most rely on public transit to make it to school for the 7:30 a.m. start. About half of the student body is African-American, with the rest Hispanic. Tuition is on a sliding scale, from $250 to $2,500 a year.

Students look to the future

Sean attended a Clayton County middle school when he lived in College Park, raised by his great aunt. Sean’s mother is in jail and he doesn’t have much of a relationship with his father.

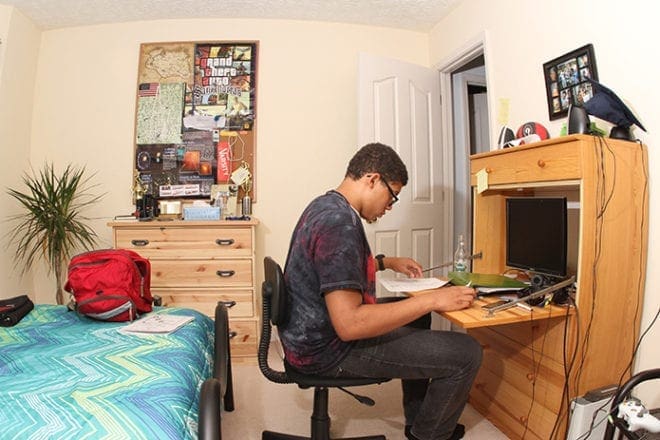

After arriving at the house from school, Sean McNeal grabs a quick bite to eat and he’s off to his room with a bottle of orange cream soda, where he works on his Latin homework. His room is filled with various video game posters, personal memorabilia and family photos. Photo By Michael Alexander

A promising student, he brought home A’s and B’s in the middle school gifted and talented program and earned two high school credits, said Sean, who is about to turn 15.

He learned about Cristo Rey from Ron Chandonia, who, with his wife, Charlene, adopted Sean’s half sister a number of years ago. The promise of the school grabbed the attention of his great aunt. Sean liked the mix of work experience and education, even if that meant doing two hours of homework nightly, while former classmates have half as much.

“I know Jesuits are known for their expertise in education,” he said.

When he thinks about the future, he accepts if school is tough now, it’ll pay off in the long run.

“Everything points to I should do this. It’s a great opportunity,” he said.

Sean stands nearly head and shoulders above his classmates, taller than 6 feet. He wears black glasses, with his hair cut short. Along with his classwork, he carries a paperback edition of the classic satire “Catch-22.” His physician challenged him to read it instead of playing video games, which he plays often. If he hadn’t attended Cristo Rey, he was slated to attend North Clayton High School, where 8 percent of the students are enrolled in the gifted and talented program.

He lives in Peachtree City now with the Chandonia family. His great aunt died in the spring after he was admitted to the school.

Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School students Sean McNeal, sitting, and Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez pose for a photo beside the school banner. McNeal has a humorous wit to go with the intellectual side of his personality. Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez clearly knows the difference and when to take him seriously. Photo By Michael Alexander

He is making his way in the school. He got an 80 on a recent English quiz. He received a 20-minute punishment to “jug,” a traditional term many Jesuit high schools use instead of detention. The term may have come from the Latin noun jugum which means “a yoke, a fetter,” meaning students are put to work. (Father Van Dyke jokingly suggested long ago students may have coined the acronym for “judgment under God.”)

Ron Chandonia heard the pitch for the school at his parish, Our Lady of Lourdes Church, and thought both the academics and character building could serve Sean well.

“I knew he was very bright and not at all satisfied with the typical urban school experience,” Chandonia wrote in an email. A retired professor at Atlanta Metropolitan College and instructor in the archdiocesan diaconate program, Chandonia tutors Sean in Latin.

A phone conversation signals what he hopes from the school. Sean recently phoned his father, whom he hasn’t seen for a long time. He called to spur his father to help improve his brother’s situation with his guardian, or at the least, to let the young man know that somebody cares what happens to him.

Chandonia said he sees Sean’s desire to leave behind the difficult circumstances he was raised in.

“I believe he agrees that the best way to do it is to avoid becoming the kind of person who hurt him so much. I believe he has resolved to do that, and I hope (and expect) Cristo Rey will help him carry out that resolution,” Chandonia wrote.

Bethy Ramirez-Sanchez, standing, teaches a third-grade catechism class with her older sister, Elizabeth, and one other instructor. The class is held on Wednesdays at her parish, St. Patrick Church in Norcross. Photo By Michael Alexander

Each school day for Bethy includes Mass.

“It’s like advice. It’s like God is our friend,” said the altar server at St. Patrick Church, in Norcross. “It just clears my mind so I can be ready to learn.”

On Sept. 2, Bethy and parents, Eunice and Manuel, and her three sisters welcomed a new addition to the family, a sister, Heidy. Bethy’s mother is a homemaker, and her father works in construction, specializing in gutter installations.

Bethy is the second oldest in the family. Her older sister, Elizabeth, attends Berkmar High School in Lilburn and has done well.

“I would’ve been so scared,” said Bethy about the size of Berkmar. The Gwinnett County high school has a current enrollment of more than 3,450 students.

Bethy is grateful as a student with limited economic means to have the opportunity to attend Cristo Rey Atlanta. Each freshman received a Chromebook with textbook apps for home use. Mathematics is her favorite subject. “Math really makes you think.”

The school’s extracurricular offerings interest Bethy as well. She hopes to participate in the debate club.

“I really want to play volleyball this year,” said Bethy, who thinks about a career in law.

“You can tell the teachers really want to help us,” said Bethy. “People here are really friendly and nice.”

Before school had even officially started, Bethy tackled homework for the Business Training Institute with enthusiasm. With just a few days’ notice, and a couple of late nights, she turned out an impressive project on skills needed for corporate work settings. A mobile and three-dimensional construction paper cube included neatly written details on using technology, making good first impressions, and “introducing yourself in under 30 seconds.”

Bethy said even the school uniform reinforces the school’s mission. It consists of a white oxford or polo shirt, blue and gold tie, gray skirt and dress socks and shoes, with blazers worn for work.

“Blue is for hard work. And gold is for excellence,” she said.

It is important to say “blue and gold” in order, because hard work comes before arriving at excellence. And not having to make wardrobe choices is a plus for this 14-year-old. “It gives us extra time to sleep,” she said.