Photo by Michael Alexander

Photo by Michael AlexanderJackson

Archbishop Visits ‘Family Of God’ At Jackson Prison

Published January 11, 2007

The male inmates endure a rigorous classification process at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Jackson upon entry into the state prison system.

Staffers of the maximum security facility determine where to transfer prisoners for their permanent prison residence. Then, assigned a number for identification, they must surrender everything. Those without work assignments may get as little as seven hours a week outside of their cell.

The iron weight of their sentences, confined to cells, begins to hang heavy on their minds, and their souls often swell in despair, absorbing the reality of their infinite, television-free time to contemplate their crime. While most had no formal religious upbringing, many eventually find themselves searching for truth, reading the Bible, attending one of about five weekly Bible studies, and attending Mass and other Christian services.

In this environment prison ministers are uplifting the banal lives of prisoners behind the bright yellow prison bars found through out the Jackson prison, which confines some 2,000 prisoners, ranging from drug abusers to murderers, and includes all of the state’s 103 death row inmates.

Deacon Tom Silvestri has been ministering there almost weekly since 1989, and Father Austin Fogarty accompanies him.

“I enjoy doing it and get a sense of doing something good for someone somewhere along the line,” said the Holy Cross Church deacon, although he may never see the result as many come and go.

On the overcast morning of Jan. 4, Deacon Silvestri and Father Fogarty, pastor of St. George Church in Newnan, accompanied Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory and archdiocesan jail and prison ministry coordinator Jim Powers on a visit to the Jackson facility south of Atlanta just off I-75. A few soaring birds occasionally squawked over the facility, surrounded by a high barbed-wire fence, dry grass, magnolia and bare trees, a few shrubs and yellow potted pansies. A woman peered through a window from atop a white tower with a red door, calling down for unfamiliar visitors to identity themselves. A prisoner sat below watching the parking lots. The archbishop and the others entered into the security room, surrendering their driver’s licenses, walking through a metal detector and hoisting the red suitcase of items for Mass into a machine for scanning. The visitors passed through a hallway lined with inspirational posters such as one stating, “leadership,” which pictured a basketball player slam-dunking, and another on “excellence.”

The hallway beyond a set of two prison bars reeked of paint fumes as some inmates in baggy white uniforms painted while others swept. In addition to the permanent population on death row, a small number stay there long term and have work assignments to keep the facility running. Others stay longer and receive special treatment for mental health needs.

The “men in black” headed into the chaplain’s office to change into their vestments, greeted by one inmate who sat at a reception desk filling out a record sheet on attendance at religious services in December. Racks in the office contain religious publications including a prison journal with the article “Integrity’s Training Ground,” and “Explore the Bible: Adult Learners Guide.”

A few inmates peeked in, inquiring about the morning Bible study that the chaplain told them was not for another hour. The archbishop, standing in the office hallway awaiting Mass, affirmed that visiting prisons is one of Christ’s clearest mandates.

“The prison ministry of the church is part of the Gospel mandate. It says, ‘I was in prison.’… It’s not something new or optional.”

He expressed gratitude for Powers, Father Fogarty, Deacon Silvestri and all involved in prison ministry who “do an important service and provide a true Gospel ministry.”

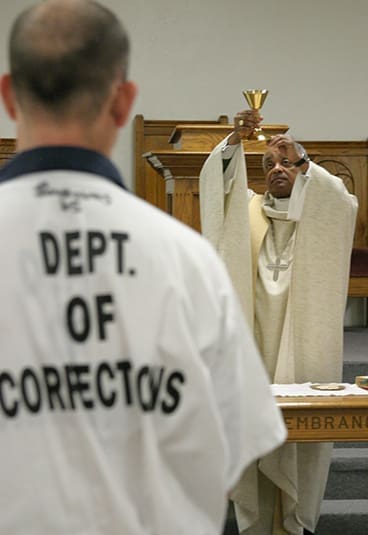

Inmate William Seagraves, foreground, attends the Jan. 4 Mass in the chapel at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison, Jackson, where Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory was the main celebrant. Photo by Michael Alexander

He hopes to assure the inmates that Jesus still can abide with them despite the gravity of their sins.

“I want to remind these men of the presence of Christ here and in them, though they might be inclined to forget they belong to Christ because of events in the past,” he said. “There may be a tendency to forget that they have not passed from the heart of the church. It’s important for the church to remind these men and women they are brothers and sisters despite their past.”

As the Mass began, inmate lectors read Scripture that resonated through the quiet chapel as about a dozen men sat in the first few pews and participated in the Mass, as air softly rumbled from the vents overhead. Nearby a sign in the brightly lit, windowless room read, “You are now entering the mission field.” Attendees repeated the responsorial psalm, “How lovely is your dwelling place, O Lord.” The men held hands for the Lord’s Prayer and shook each other’s hands during the sign of peace.

The archbishop wished them a Merry Christmas season and “Feliz Navidad” and said they were “gracing my time” with the visit during the Christmas season, which is a time for families to come together. He assured them that they are not forgotten but integral members of the body of Christ and the church of North Georgia.

“It’s very important for me, for deacons, priests, Religious and lay people to recall that you, men, are part of our family of God, the believing community, and so we come to share the mystery of Jesus being born here anew.”

While there is plenty of struggle in prison, he cited from the Scripture reading how even the Holy Family struggled as Mary and Joseph fretted when they lost Jesus who stayed behind at the temple in Jerusalem. The archbishop continued by saying that Jesus is present for those who are sick, imprisoned and others on the margins of society where “the family of the church may more perfectly recognize the Lord.”

Some spent a few minutes kneeling before the altar after receiving Communion. Afterward, the archbishop greeted and shook the hand of each of the men, one of whom kissed his hand.

Then he and the others proceeded into a 20-by-7-foot barbershop to celebrate Mass for five death row inmates, where journalists were denied access.

General population inmate Steve Cirri volunteered for an interview following the liturgy. While he has applied unsuccessfully to get a job in the kitchen, the inmate in his mid-50s now spends most of his time in his cell where he sits on the bunk bed that he shares with his cellmate. He is completing his third entire reading of the Bible since his incarceration. He has 14 months to serve of his three-year sentence for obscene Internet contact with a minor.

Cirri pulled out his Bible, stuffed with pamphlets, to show a certificate stating his ordination in the Universal Life Church, although he explained he is a Catholic and was raised in an orphanage run by nuns and priests. He regrets his crime but states he didn’t know it was illegal, explaining that he wrote e-mails with sexual content to a minor over the Internet but never met or spoke with her. He is now registered as a sex offender for life. He worries, too, that he’ll be homeless when he is released, as many transition houses don’t allow sex offenders.

“I think I got a bum deal as being signed up as a sex offender. I can do the three years because I did write the e-mails. But as a sex offender, I’ve been praying to God to take that burden from me,” he said. “Once you see sex offender, they think child molester.”

He basically “lost everything” down to any privacy in his small cell with a toilet and barely any room to walk around. He yearns for his 3-year-old son, whose mother ended their four-year relationship and severed contact with him following his imprisonment. Cirri, who has a tattoo with his son’s nickname, Domo, and six teardrops on the inside of one arm, finds comfort especially in reading the Book of Job, a man who suddenly lost everything but his faith.

“We sit here and feel sorry for ourselves. I say, read Job. This man lost everything, the devil gave him sores, and he never lost his faith. … This gives me comfort, to say hey, what I’m going through ain’t nothing compared to what he went through.”

He recalled lying on his bottom bunk one day and experiencing healing.

“I said, ‘Wait a minute. Jesus didn’t forsake me. I’ve forsaken him.’ When I said that I felt something raised right out of my body,” he recalled. “I pray to God every day. … People can’t see how much I regret what happened, what I did. I made a mistake and I’m suffering for it, and my poor baby is suffering, too.”

He looks forward each week to the Mass and when appropriate shares his faith with other inmates and encourages them to study Scripture. He arranges readers for Mass. “(The liturgy) lifts you up and makes you feel Jesus loves you and is still here with you, and no matter what, he will always be there for you and help you even if it feels like he’s not. It gives me spiritual food. To me it means a lot especially when I take the bread of Christ. I can feel Jesus inside of me more than when I’m just praying. I feel cleansed.”

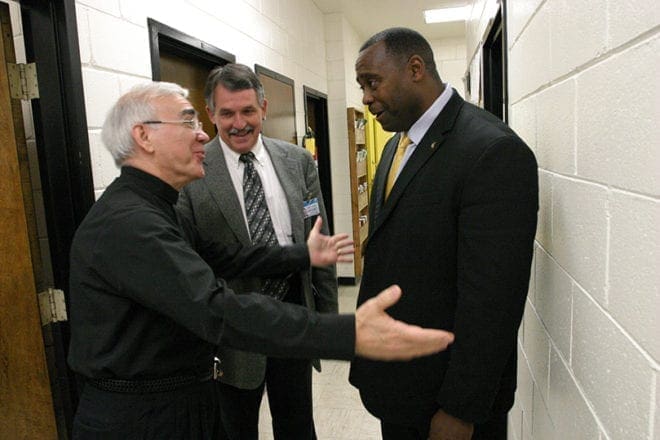

Deacon Tom Silvestri, left, welcomes new warden Hilton Hall, right, during their initial meeting following Mass. Looking on is Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison director of chaplains Rev. Stanley Harrell. Photo by Michael Alexander

After leaving the orphanage where he was an altar boy, he said he drifted from his faith, but “I never forgot Jesus—well, I guess I did, because I’m here.”

Inmate Samuel Ray had a previous cellmate who was Catholic. He is very interested in converting to the religion that he finds more connected directly to the early church and to Scripture.

“I like the way they handle the service. They, Catholics, cut to the point, exactly what happened back in the day,” he said. The archbishop “is wonderful.”

“I’ve heard about him before. He’s really good, talking about how all the people who love the Lord, whether you are a prisoner, we’re all God’s people.”

Now 36, the blue-eyed Ray started using drugs at age 12 and never got caught until he was 31. “It’s nobody’s fault but mine. That’s the punishment you get for doing wrong.”

Newly imprisoned, Ray was convicted in Cobb County for cocaine posession. He, too, is spending most of these days reading and has also turned to Scripture. He savors the Proverbs, which he feels are meant just for him. But his favorite verse is from 1 Corinthians, chapter 13, on love.

He has six children and hopes to be a good father to them upon his release.

“I’ve got to really get out there and do what the Lord says in the Bible and be a father to those children,” he solemnly affirmed. “What I want to do is turn my life around—Lord willing.”

Methodist minister and director of chaplains, the Rev. Stanley Harrell, said that he emphasizes education with about five weekly Bible studies, as 99 percent of the men have had no formal religious upbringing, although they might identify with a religion because “grandma was.” Various faith groups minister there, including Muslims, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Protestants. He spends a couple of hours every morning meeting privately with individual inmates where he provides a safe space for them to express their feelings about their sentence, whether anger, fear, despair or regret, and to find hope in Christ.

“My office is the only place inmates can cry and get angry and not get in trouble. (I work by) helping them to see God is as real here as he is anywhere else,” he said. “You’re locked down, and it’s reality. They start the grieving process. … I don’t know how folks get through regular life without God so how are you going to do time without God? That’s the only place they will get a sense of hope, not hope (in that) everything will go your way, but knowing God is still present and can do things with your life if you let him. Death can come and then resurrection.”

In prison they can no longer deny the reality of their sentence, he said, adding that those on death row spend an average of 15 to 16 years until their execution.

“They just want to be remembered, to be known and not forgotten. This place will swallow you up. When they come here their name is taken, all their personal belongings. You’re a number now.”

Inmates Samuel Ray, foreground, and Michael Laytart stand during the prayerful petitions. Photo by Michael Alexander

Warden Hilton Hall said that the majority of prisoners stay at Jackson fewer than five weeks as security and any special needs and skills are evaluated. They are assigned a “platoon leader,” who leads them in prison life, where their privileges such as phone calls and visitation are restricted until they get to a permanent facility.

“There is an adjustment for most of them of being told when to get up and when to go to bed, the whole structure part of being in prison is primarily done here. We show them how. We bring them in and form a platoon like in the military,” said the tall, large-framed warden wearing a dark suit. “We are trying to instill in them ‘you’ve got to listen to that platoon leader to get through this process and out of this facility.’ That pretty much motivates them to get through the diagnostic process.”

Director Arnold Depetro of the Corrections Division of the Department of Corrections spoke with Archbishop Gregory during his visit about the need to have the Catholic community more involved in helping to support prisoners transitioning back into society upon their release. He said the department is becoming more collaborative as it’s a community effort to support ex-offenders in the transition with critical needs such as jobs, housing, mental health care. Re-entry support “is doing the individual and the community a great service.”

He added that among their varied programs to change behavior and value systems they’ve introduced a new intervention initiative for middle schools, as too many parents begin treating their adolescent children like adults and leave them alone, which is when they get into trouble. When prisoners are discharged, “if there is after-care and follow-up, their chances increase dramatically (of adjusting well), and without that what happens is they get released from the institution and they don’t have anything to look forward to.”

Deacon Silvestri said the majority of people in Jackson have committed crimes related to drug abuse, and said most prisoners, except those on death row, will have some opportunity for rehabilitation. He says of his ministry that “many times I didn’t want to go there, but I’ve always felt very glad on the way home that I went there.”

“They are at least getting to have an opportunity to get out of their cells and go where somebody is not going to be screaming in their ears. If I can provide some relief, it makes it worthwhile.”

Jail and prison ministry coordinator Powers found the visit with the archbishop to be a “wonderful personal experience.” He and other members of Pax Christi had begun writing those on death row about 10 years ago, and he has corresponded with two of the men who attended the Mass on death row and knew a third. One attendee has been on death row for 32 years, and “we had a great chat.” He also has ministered to another death row inmate of 20 years, where he said his philosophy is “to be a friend.” He recalled how when they first came in contact the inmate told him “if you are coming here to do all that Christian baloney, don’t bother.”

“Really it’s to be there, and he phones and we exchange correspondence,” he said.

Powers reported that every year about 18,000 Georgia prisoners are released and within three years about 12,000 will be back in prison, and that about 65 percent of people leaving prison nationally will be back in three years. There are about 53,000 adult prisoners in Georgia.

“That’s been a constant (recidivism) figure for 20 years, both nationally and in Georgia.”

To help reduce that rate, he is now working to implement this year in Georgia a prison program called Thresholds. The six-step program, designed by an ex-offender with a Harvard doctorate, helps prisoners to make intelligent decisions and solve problems before and after release. It involves workbooks, assignments and class sessions. So far about 20 people have been trained, and he’s looking for more volunteers and hopes to speak at churches about it. This program is replacing their One Church One Inmate program, Powers said, as the non-religious Thresholds was established in 1972 with proven success in reducing recidivism. He explained that many, upon re-entry into society, struggle to make even the smallest decisions such as what food to order, which makes more important choices difficult.

“It’s a training program to train prisoners on how to learn to make decisions in their lives without just reacting to the world around them,” he said. “It’s doing what parents do with adolescents because an awful lot of these people never received training on how to make a good decision in their life.”