Finding solace in the art of J.R.R. Tolkien

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published September 18, 2015

In memory of Jeffrey Patrick Murray

17 March 1960-3 August 2015

Like all of us at The Georgia Bulletin, and like the many readers who follow Lorraine Murray’s column in the newspaper, I was shocked and grieved to learn of the sudden death of her beloved husband Jef.

Lorraine’s recent eloquent and moving columns devoted to Jef say far more about the man than I can; I did not know Jef well, but like many artists he seemed to possess a quiet strength, and I sensed he was perhaps best understood through his art, which served as a frequent complement to Lorraine’s writing.

In fact, the last time I saw Jef, he was with Lorraine, supporting her as he always did. Lorraine had come to my senior English seminar to share with the class her experience in writing one of the first biographies of Flannery O’Connor. Jef wore one of his unique hats, and as he listened quietly with the rest of the enthralled class, I noticed that he was occasionally sketching.

It was easy to see that this man had learned how to balance his love for his wife and his love for his work in a fully integrated vocation. His family and his art were inseparable; each depended upon the other.

So it was with Jef’s great inspiration, the beloved writer and artist J.R.R. Tolkien, who over the past 20 years has transcended his once underground following to become a name known all over the world.

So it was with Jef’s great inspiration, the beloved writer and artist J.R.R. Tolkien, who over the past 20 years has transcended his once underground following to become a name known all over the world.

Tolkien’s literary works have been translated into a myriad of visual interpretations, from cinematic adaptations to graphic novels. Some are stunning, some bombastic, and most of them miss the quiet, gentle whimsy and mystery with which Tolkien himself illustrated his work.

From looking at Jef’s art, it is easy to see that he understood the simpler, and therefore more profound, aspects of Tolkien’s visual imagination. He understood that Tolkien’s vision was informed by wisdom, playfulness, faith, and love. Jef’s paintings of Tolkien’s Middle Earth are wonderful. They evoke, I think, precisely what Tolkien intended, but they become unique works entirely Jef’s own. My favorite is “Hobbiton,” which captures beautifully the innocence and wonder that herald Bilbo Baggins’ adventure.

How do those of us who convert to Catholicism come to the gift of this great faith? Some come for marital reasons. Some come because they hear a compelling homily, or observe the great witness of public Catholics. Some are drawn by the beauty of the liturgy. And some come because of art and the example of Catholic artists.

The great Catholic aesthetic tradition drew me into the Church, and it captured Jef’s imagination as well. More importantly, it enriched the seed of his faith.

In his classic essay, “On Fairy Stories,” Tolkien fully articulates some key points of his vocation as a Catholic artist. I am sure that Jef knew this essay, and I am confident he fully believed what Tolkien expresses in it. On the one hand, Tolkien argues that the Catholic artist is rightfully called a “sub-creator.” He uses the gifts God has given him—intelligence, imagination, curiosity, the senses, and language—to interpret and articulate the mystery of God’s love for His creation. In making art, the sub-creator therefore has some share in the glory and wonder of God’s own joy in creating.

Further, the Catholic artist—particularly the one who works in the realm of fairyland—understands that the highest aim of his work is to achieve a sense of what Tolkien called “Eucatastrophe,” which Tolkien described as “the Consolation of the Happy Ending … the joy of the happy ending … a sudden and miraculous grace.”

Did Jef Murray have a happy ending? Many in the world would say not, but Tolkien, like all Catholics, knew better. You see, Tolkien elaborates further upon the Eucatastrophe to say that “it denies universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

This is the great mystery of Christianity, the paradox of finding joy in grief. Grief is real; grief is painful. Lorraine knows it, and she is living in it now. So are all who have recently experienced the death of loved ones. And yet Jef knows now only joy, a peace that passes our own understanding. This is exactly the Catholic quality that Tolkien was able to express in his work.

Even Gandalf, the adored wizard who appears in both “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings,” has to experience death. Yet he experiences the resurrection as well. Is it any coincidence that Tolkien subtitles “The Hobbit,” “There and Back Again?” The Eucatastrophe, Tolkien said, gives us still living “a brief vision that the answer may be greater—it may be a far-off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world.” Tolkien goes on to demonstrate that the Gospel is the greatest example of Eucatastrophe, and an acceptance of this belief leads the believer—even in her grief—to a fuller faith in our share in the Resurrection, the gift of the Holy Spirit, and the comfort of the Communion of Saints.

Tolkien expressed this faith not only in his work but in the example of his life. In fact, Tolkien was primarily responsible for the conversion of his friend C.S. Lewis, another spiritual writer whose Narnia tales Jef illustrated. Tolkien convinced Lewis that their shared belief in the power of myth was a stepping stone to a greater faith in Christ. Lewis argued that myths were “lies.” “No,” Tolkien asserted, “they are not lies.” They are instead, Tolkien went on to explain, the basis of belief in our own participation in salvation history. Lewis converted, and went on to become one of the greatest modern Christian apologists. Countless others, including Jef Murray, read the account of Tolkien’s evangelism of Lewis and accepted the gift of Catholicism.

In the four decades since Tolkien’s death, much more material has surfaced that supports the depth of Tolkien’s faith. His letters, in particular, reveal a profound devotion to the Eucharist. The work that he created for his children supports his vocation as a loving father; indeed, one of his sons went on to become a Catholic priest while another has been a gracious and brilliant steward of his father’s legacy.

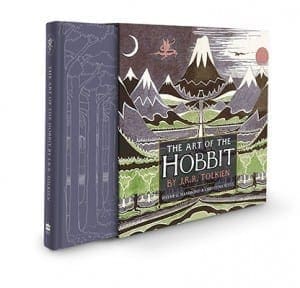

Among the recent numerous additions to the canon of Tolkien scholarship is the wonderful collection edited by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, “The Art of the Hobbit.” Published in 2012 in celebration of “The Hobbit’s” 75th anniversary, the book collects all the illustrations that Tolkien drew and painted as he was writing the book and preparing it for publication in 1937. Many of these illustrations have never been seen; those that were published are here presented in beautiful reproductions.

As the editors of the book note, “the pictures, no less than the text, serve to draw the reader into the world of The Hobbit.” In doing so, the illustrations lead the viewer and reader into a greater appreciation of the Eucatastrophe. We are marveling not so much at a world different from our own, but reveling in the joy of discovering its similarity. If there is hope for Bilbo; if there is life after death for Gandalf; if even the corrupted Gollum can experience pity and mercy, then surely we too must be able to experience this grace.

I know that Jef Murray adored Tolkien’s illustrations, and if you have not seen them in their entirety, then you are missing a crucial part of Tolkien’s work. To view this work is to enter more fully into Tolkien’s imagination and faith, a faith that affirms our belief that while we all must come to an end, we begin—again—in joy.

David A. King, Ph.D. is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.