Ford’s “The Searchers”: Connection And Redemption

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published May 23, 2013

Roger Ebert, who died recently and was perhaps the most important 20th-century apologist for cinema as both popular entertainment and serious art form, said of the relationship between movies and our collective imagination: “We live in a box of space and time. Movies are windows in its walls.”

Binx Bolling, in Walker Percy’s novel “The Moviegoer,” affirms Ebert’s statement. As Binx says, “People, so I have read, treasure memorable moments in their lives. … What I remember is the time John Wayne killed three men with a carbine as he was falling to the dusty street in ‘Stagecoach.’”

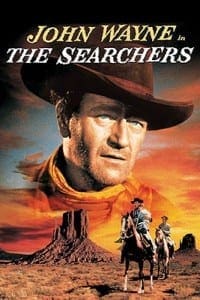

The 1956 masterpiece by John Ford sets a man’s search for his kidnapped niece against the backdrop of Monument Valley. The film transcends stereotypes associated with the Western genre and endures in the canon of great movies.

Both Ebert and Binx are right: one great connection we all share is our sense of collective memory of experiences at the movies. In the dark, we come together as strangers, and when the projector illuminates the screen, we become participants in a ritual charged with the overtones of a religious ceremony. It’s no surprise that the great director of widescreen epic films, David Lean, said of going to the cinema that for him it was like entering a cathedral.

In American cinema, only a very few filmmakers have fully understood the power of the motion picture to engage audiences in a world that is paradoxically entirely separate from their own reality, yet mirrors that reality at the same time. Of them, John Ford is perhaps the most remarkable, and his 1956 masterpiece “The Searchers” offers the best introduction to his defining style and compelling themes, many of which are informed by his Catholic imagination.

Ford’s life and career are both fascinating, for he seemed to live a life as adventurous as that of his characters. Born in 1894 to Irish immigrants in Maine as Sean Aloysius O’Feeny (if one believes Ford’s own account of his origins), he came into the movies in the early silent era, shortly after arriving in Hollywood in 1914. He worked on close to a hundred films with some of the greatest pioneers of the early cinema, and made an incredible number of great movies until his death in 1973. Throughout his long career, he won Academy Awards for Best Director four times, Best Picture in 1941 for “How Green Was My Valley,” and Best Documentary in 1942 for “The Battle of Midway.” Indeed, Ford was deeply patriotic and committed to the cause of World War II; he was wounded while filming the combat at Midway, and he landed on Omaha Beach during the Normandy Invasion on D-Day. His best known films remain staples of both art-house revivals and television retrospectives and are as relevant to ordinary audiences as they are critics and cinephiles: “Stagecoach,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” “Young Mr. Lincoln,” “The Quiet Man,” and—of course—“The Searchers.”

“The Searchers” was shot, like so many of Ford’s great Westerns, primarily on location in Monument Valley. It stars Ford’s greatest collaborator, John Wayne. It is perhaps Ford’s greatest visual achievement; shot in a widescreen aspect ratio, it almost has to be seen on a big screen to be fully appreciated. The critic and filmmaker John Milius has said of Ford’s work in “The Searchers” that “Ford was having a love affair with the land,” and this quality is apparent in almost every shot.

In these characteristics alone, Ford reveals himself as a fundamentally Catholic filmmaker. He relies upon, and trusts in, the iconography associated not only with the Western genre but also the movie star John Wayne. He recognizes humanity’s often lonely and isolated existence in the natural world, and yet he insists that the individual is nonetheless part of that natural world. Most importantly, as the film eventually asserts, human beings cannot be alone; as part of nature, and as part of community, they were created to love one another.

The film is based upon a true story of a girl who was kidnapped by Comanche Indians, but Ford shifts the emphasis from the Indians to that of the man who searches for the girl. The film opens as Ethan Edwards, played by John Wayne, returns to his brother’s home following the Confederate defeat in the Civil War. Edwards is hardly reconstructed; indeed, he still wears his Confederate uniform. And he’s bitter, both about the defeat of the war and the family’s acceptance of Martin Pawley, a young man of mixed Indian and white ancestry who insists upon calling Ethan “Uncle.” Shortly after Ethan’s arrival, a Comanche raid upon the homestead results in the violent deaths of Ethan’s family. Ethan and Martin, who have been lured away by a Comanche ruse, return home too late. They discover the bodies of the dead, and they learn that the youngest daughter—Debbie—has been taken by the Indians. Ethan vows to search for Debbie; Martin insists upon coming with him. Through the course of their search, Ethan and Martin discover that Debbie has been taken by a Comanche chief named Scar. The quest for vengeance against Scar becomes an obsession for Ethan, a maniacal quest driven more by hatred for the Indian than by love for the missing girl.

Ethan’s racist hatred becomes the real emphasis of the film; it’s the story that really interests Ford more than a conventional chase film, and certainly more than the familiar aspects of the Western. Like all great Westerns, what the critic Andre Bazin called “the American film par excellence,” “The Searchers” transcends the stereotypes associated with the genre to create something ultimately more compelling and universal.

Ford had seen the effects of hatred in World War II. He knew the consequences of unchecked power, as he lived and worked during the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings that placed the film industry at the center of the anti-communist witch hunt. He knew, as a citizen of the United States in the 1950s, the tragedy of racism and the challenges of the civil rights movement. He came to “The Searchers” as one might approach confession; the making of the film became for him like an examination of conscience.

At the same time Ford confronts the issue of racism, he also affirms his great themes of the frontier, the family, and the community. For Ford, like all great Western directors, the allure of the frontier represents the great American myth, a mythology unique to this country, and one particularly appealing to the immigrant. His insistence upon preservation of the family is a motif that runs throughout the film. Most of all, he asserts that we are all part of a singular human community. As a Catholic, Ford intuitively understands the rituals we associate with family and community. The movie includes a number of subplots, all of them featuring social rituals: the sharing of meals, the reading of letters, helping one’s neighbors. There is even a wedding, a favorite Ford device.

In “The Searchers,” Ford made a film that nearly 60 years later has endured as an essential part of the canon of motion pictures. Decade after decade, it appears on the famous Sight & Sound Top Ten poll, and any list of the best Westerns always includes it as one of the greatest Westerns ever made. The movie has all the action one expects from a Western, yet that is not what draws people to it year after year. We watch “The Searchers” on one hand because it is visually stunning; against the backdrop of the buttes and canyons of Monument Valley, we project ourselves into the universe they are meant to represent. We see ourselves as small, perhaps even insignificant. Yet we also see what Ford, as a Catholic, most wants us to see—that we are connected to one another; that we are capable of redemption, even from ignorance and hatred; that each of us has a purpose and a responsibility to the greater good.

In the film it finally becomes clear that what Ethan is really searching for is his soul. At the conclusion of “The Searchers,” in one of the most iconic shots in the American cinema, John Wayne stands in a doorway not as soldier, nor stranger, nor even savior. He stands as a seeker. He stands, truly, as a pilgrim.