Iconic sportscaster Jim McKay affirmed life through love of sports

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published February 19, 2015

Ernest Hemingway is often cited as proclaiming that “There are only three sports: bullfighting, motor racing and mountaineering; all the rest are merely games.”

I wish Hemingway could have known my 4-year-old son, Nicholas, whom we affectionately call Nicky, or just as often, “the Bubba.”

Last week, you see, the Bubba beat his daddy at Candy Land for the first time; he drew an ice cream floats card from the top of the deck and on his first move traversed nearly the entirety of the board toward the finish. In a matter of draws, he was safe at home sweet home while I languished somewhere in the peppermint stick forest.

He was absolutely delighted, as was I, for we shared a wonderful moment that evoked my own childhood playing games with my father, who died before Nicky was even born. In that moment of childhood sweetness, Nicholas and I not only bonded as father and son; we brought back the past.

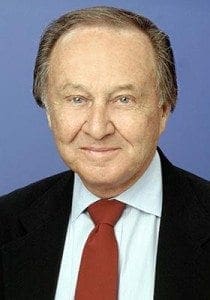

Jim McKay, the legendary sportscaster, hosted numerous Olympic Games and was the network staple for ABC’s “Wide World of Sports.” Photo By CNS

Clearly, there was nothing “mere” about our Candy Land game.

We’re learning lots of games at our house now, for I believe strongly that classic board games and sports are ideal ways not only to grow closer as a family, but also to instill values of fair play, cooperation, and strategic and critical thinking. Candy Land is just a game of chance; chess is by turns sport, science and art, but they and all the games in between are meant, most of all, to be fun.

Sports is meant to be fun

In many ways, our society is slowly taking the fun out of sport. Pre-game shows last longer than the actual events. Post-game analysis is tedious and often dull. Blogs and talk-radio inspire vitriol and mind-numbing repetition of ludicrous statistics. In our own lives, our children’s organized sports have become far too demanding upon our time, encroaching now even on Sundays and jeopardizing family time, faith formation, and attendance at Mass.

Oh to be back in the 1970s, on a Saturday afternoon, tuning in to the ABC anthology program, “Wide World of Sports,” which brought into the American living room the panorama—and sheer joy and thrill—of the “mere games” of the world.

If you are of a certain age, the opening theme of the program is engrained forever in your imagination. Over a montage of fantastic images, a solemn voice intoned with excitement, “Spanning the globe to bring you the constant variety of sport, the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat, the human drama of athletic competition.” Remember the fantastic car crash? The brute with the barbells? The colossal wreck of the skier? Of course you do!

Do you remember the voice? Catholics especially should know it. It belonged to James Kenneth McManus, better known as Jim McKay.

Sportscaster linked to beloved national events

Jim McKay is arguably the greatest American sports broadcaster of the 20th century. For generations of Americans, McKay is inextricably linked to some of our most beloved national events, including the Kentucky Derby and the Indianapolis 500, and he was the first to bring to America’s attention a spectrum of world sports that are now enormously popular in the United States, among them English soccer and Formula 1 motor racing. McKay’s wide world even included Hemingway’s favored bullfights and mountaineering. In fact, if it had anything to do with competition, from international chess championships to the lumberjack games, it aired on “Wide World of Sports.”

Most of all, McKay became synonymous with television coverage of the Olympic Games. His remarkable 16-hour reporting on the 1972 games in Munich, in which he transcended his role as sportscaster to become both journalist and mourner, is a cultural milestone of the 20th century. As armed terrorists invaded the apartments of the Israeli Olympic team, taking hostages and making grave threats, McKay stayed on the air to monitor the crisis. Tragically, at the end of the long ordeal, 11 hostages had been killed.

The moment ranks with John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father’s casket, the evacuation of Saigon, the shootings of St. John Paul II and Ronald Reagan, the Challenger disaster, and the collapse of the World Trade Center as among the most iconic television images of the latter half of the 20th century. People remember the terrorists lurking in the foyers of the Olympic apartments; they remember the faces of hostages and killers as McKay described them, “popping out of windows and doors regularly like some sort of dreadful puppet show,” and they remember McKay, exhausted, staring into the camera and reporting sadly, quietly, “they’re all gone.”

It was the peak of McKay’s career, and perhaps the only time in which he couldn’t couple his love for intrigue with joy.

Journalist started at newspaper, moved to television

McKay was born in 1921 in Philadelphia, into an Irish-American devout Catholic family. He was educated in parochial schools in both Philadelphia and Baltimore, and graduated from Loyola College. He had a dangerous job as a Navy minesweeper in World War II, and after the war came home to begin a career in journalism. While working at The Baltimore Sun, McKay met his future wife, Margaret Dempsey. They married in 1948, and their marriage endured for 60 years, despite McKay’s constant travel around the world, until his death in 2008.

McKay gave up his job at the newspaper when television came into prominence; in fact, his was the first voice broadcast on Baltimore television. McKay worked for a few years with CBS, serving as an early broadcaster of televised pro football games, but in 1961 he went to ABC to work on a new show envisioned by Roone Arledge. He stayed as host, and then perpetual contributor, of “Wide World of Sports” for 37 years.

It didn’t matter to McKay what sport he covered, for he brought to every game, every match, every event the same sense of curiosity, amazement, empathy and respect. In the 1970s, McKay might have been the only male over the age of 12 who took Evel Knievel seriously!

Still, McKay’s favorite sporting events, besides the Olympics, were clearly horse racing and auto racing. McKay was deeply involved in the development of the Maryland horse industry, and in retirement, he enjoyed a quiet life on his beloved horse farm.

Yet his love for motorsports reveals perhaps more of his personality, both empathetic and wise, than any other sport he covered. Because the racing driver constantly works with death at his side, he is usually either a person of great stoicism or great faith. As a Catholic, McKay appreciated this dilemma of having to choose life as meaning either nothing, or being connected eternally to everything.

Of motor racing, McKay was one of the few sportscasters to understand fully the nature of the sport. We watch racing, he said, not because of “spectacle, horsepower, or a ghoulish anticipation of death.” In fact, he asserted, “we watch, not hoping for death, but wishing to see men defy death, approach it, and conquer it. We identify with the driver, alone, in his machine, on the race course, a frail and vulnerable human being.”

My Nicholas loves motor racing, too. He watches it with me on television, as I did years ago on “Wide World of Sports,” marveling with Jim McKay at the exploits of great drivers such as Jackie Stewart, Mario Andretti, Bobby Allison and A.J. Foyt. The Bubba would have loved Jim McKay.

But I think what he would most appreciate about McKay is not so much his love of sport, but his gentle manner and his insightful understanding of what sport really means.

Not many of today’s sports pundits and “analysts” would have the sensitivity to include in their summation of the tragedy of the 1972 Munich Olympics a recitation of A.E. Housman’s great poem “To an Athlete Dying Young.”

Further, it speaks to McKay’s firm Catholic faith that he concluded his 1972 Olympic broadcast with the unscripted and completely sincere affirmation that “neither madness nor violence nor unspeakable atrocities can stop the spirit of man to keep living; to try to make something out of the world as it is.”

McKay practiced his Catholicism devoutly but quietly. He did his job, broadcasting sports, and nurtured his wife and children, Mary and Sean, in their lives, faith and work. Indeed, his son went on to become president of CBS sports. He also is a frequent speaker at Catholic colleges and has been awarded an honorary doctorate in humane letters from Notre Dame of Maryland University.

McKay had a funeral Mass at his parish in Baltimore, but prior to that private event, a public memorial service was held at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore. Dozens of famous broadcasters and athletes made tributes.

Perhaps the most eloquent, befitting the legacy of a man who literally took viewers all over the world, was that of Grand Prix champion Jackie Stewart, who was McKay’s friend and colleague even after Stewart retired from racing: “He was the first man I spoke to when I got in the car, and the first man I spoke to when I got out of the car.”

In an era when living in the moment has become more difficult than ever, we can learn from the example of Jim McKay, who made his life out of being there, no matter where there might be. And we can be grateful that he made sure we went there with him.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.