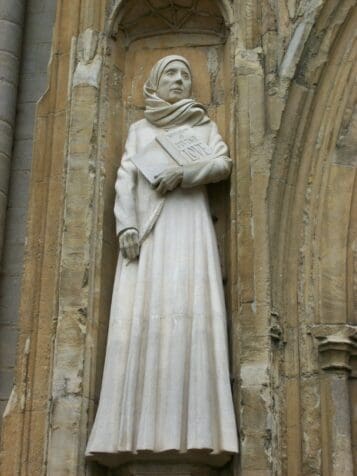

Julian of Norwich, a voice of hope

By MICHAELA MULQUEEN, Special to the Bulletin | Published March 31, 2022

Immense pain overcame the woman as she lay in her bed. Those around her feared she was on the verge of death. A priest was summoned, and upon his arrival, he held up a crucifix in front of her. He coaxed her to look at it and be comforted in what would likely be her final moments.

Michaela Mulqueen

The ailing woman mustered all of her remaining strength to gaze at the crucifix. While contemplating it, she placed herself at the foot of the cross and united herself to Christ’s sufferings, desiring nothing more than to suffer with him. She watched as blood began flowing from the crown of thorns on Jesus’ head. Unbeknownst to all in the room, this woman would not die, but God instead would reveal his divine love through her.

Julian of Norwich, born around 1342, was an English mystic, anchoress, theologian and author. Like many medieval holy people, there is little known about her personal life. However, it is known that, at age 30, she contracted a serious illness. For three days and nights, she lay in what those around her believed to be her deathbed, but it was during that time she received 16 “showings” from God.

Through the intense visions Julian received, God revealed his omnipotence and great love for humanity. She was shown both the bliss of heaven and the suffering Jesus endured for our sake. The most well-known aspect of her showings came from her 13th vision. Here God tenderly revealed, “It is true that sin is the cause of all this suffering, but all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

Julian, recognizing the importance of what God had revealed to her, wrote the 16 showings down. These writings would aptly come to be known as the Revelations of Divine Love. Today, Julian is credited as the first woman to write a book in English.

Revelations of Divine Love is divided into two parts—the Short Text and the Long Text. It is believed that the Short Text was written soon after her recovery, while the Long Text was written close to 20 years later, after much prayer and reflection on her visions. The Long Text both expands on the writings found in the Short Text and presents new ideas not originally included, such as the image of God as a mother.

Julian of Norwich wrote of hope in a hopeless time.

It is important to recall that during the time which Julian lived, sexist beliefs, prevailed in both society and the church. Consequently, women were not permitted to teach on matters of faith; they likely would have been cast aside as heretics if they did. Nevertheless, Julian knew it was God’s will for her to write down what he had so lovingly shown her. She knew God’s love and mercy were and would always be far greater than any fears she had.

In chapter six of the Short Text, Julian says, “Just because I am a woman, must I therefore believe that I must not tell you about the goodness of God, when I saw at the same time both His goodness and His wish that it should be known?”

As an anchoress, Julian would have spent the majority of her days in complete isolation. According to the regulations of the time, cats were often sole companions for an anchoress. Images of Julian frequently include a cat for this reason. However, it is known that before her death sometime after 1416, Julian counseled fellow mystic Margery Kempe, who would become the first person to write an autobiography in English.

The church has long recognized the importance of Julian and her work. She is even cited in the catechism. It is indisputable that Julian’s impact on the church has lasted centuries, so it may come as a surprise that Julian is not an official saint in the Catholic Church. Those who venerate her, however, celebrate her feast day on May 13.

Despite her lack of sainthood, an article published in 1997 by Father Giandomenico Mucci indicated that she was on her way to becoming a Doctor of the Church. If this is the case, she will presumably have an equivalent canonization like St. Hildegard of Bingen.

Throughout Julian’s life, she encountered the Black Death, division within the church and the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. A pandemic, political tensions and violence. This sounds eerily similar to modern times, doesn’t it? And yet, unlike many today, Julian knew that all earthly difficulties and problems were minuscule compared to the depths of God’s love and mercy.

She wrote of hope in a hopeless time. With talks of war, tension and uncertainty seemingly at every turn, hold Julian of Norwich’s words in your heart and know that all shall be well, for God is in control.