Photo by Thomas Spink

Photo by Thomas SpinkAtlanta

Panelists share experience of ‘waking up’ to death penalty injustice

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published February 22, 2018 | En Español

ATLANTA—Some 400 people heard from a panel of religious and legal leaders opposed to the death penalty at Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church Feb. 15.

The panel consisted of spiritual leaders of the Catholic and Episcopal churches in north Georgia, a former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia, a lawyer who has represented a death row inmate and Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ, a well-known author and advocate against the death penalty.

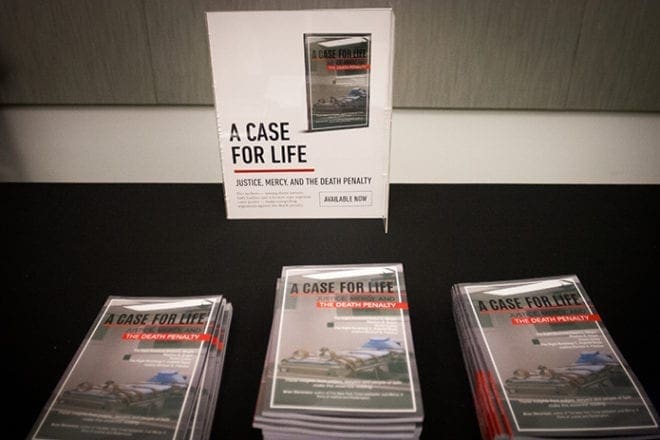

The evening event included a book-signing reception for “A Case for Life: Justice, Mercy, and the Death Penalty.” Three of the panelists contributed essays to the book.

The death penalty event at Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church, Atlanta, included a book-signing reception for “A Case for Life: Justice, Mercy, and the Death Penalty.” Three of the panelists contributed essays to the book. Photo by Thomas Spink

Sister Prejean’s advocacy was made famous in her 1994 best seller, “Dead Man Walking: The Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty That Sparked a National Debate,” which became an Academy Award-winning film. She shared her story of starting as a suburban parish religious education leader to moving into public housing projects in New Orleans and being exposed to the criminal justice system. The daughter of a successful Baton Rouge attorney, Sister Prejean said she learned from the residents how the law works differently for poor people and rich people.

“Culture closes our ears” to injustice, she said, but the Gospel awakens people.

“It’s such a grace to wake up,” she said. “Our life takes a different direction.”

Her ministry to death row inmates happened with no warning. A woman simply asked her to write to a prisoner. And then the ministry took off as she learned more about the legal system, she said.

“When God calls us, we do our little bit,” said the sister.

She said being with death row inmates exposed her to the “secret ritual” of executions. Sister Prejean said she wrote her book to shed light on what happens behind closed doors.

She wrote “Dead Man Walking” more than 20 years ago, but she has adapted to the changing times. She shares her ministry almost daily with nearly 67,000 Twitter followers.

In 2016, the state of Georgia executed prisoners at a fast pace. Nine men were executed in 2016, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. One man was put to death that year.

The pace of these killings bothers Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory, who participated in the panel forum. A resident of Georgia for a dozen years, the archbishop said he enjoys living in the community—except for the death penalty.

“We have a wonderful state. I just wish we weren’t so aggressive in putting people to death,”he said.

Archbishop Gregory said he writes frequently to the State Board of Pardons and Paroles urging its members to commute the sentences of death row inmates to life in prison. He said people guilty of serious crimes can be punished without lethal injection.

In his remarks, Archbishop Gregory said the Catholic Church has evolved on capital punishment with statements by recent popes, starting with St. John Paul II and the Catechism of the Catholic Church in 1992. He said the pope then listed the death penalty for the first time alongside abortion and euthanasia, giving the three issues equal moral weight. Archbishop Gregory said church teaching has moved from a position of being “permitted, but not to be preferred” to “contrary to the Gospel” as Pope Francis has stated.

Episcopal Bishop Robert C. Wright said he also went through a process of “waking up” to the injustice of the death penalty. He said that too often victims and survivors and prisoners are pitted against each other.

Episcopal Bishop Robert C. Wright was one of the featured speakers at the Feb. 15 death penalty panel at Holy Innocents’ Episcopal Church, Atlanta. Shown in the background is lawyer Susan Casey, who was one of the lawyers for Kelly Gissendaner, who was executed in 2015 and the first woman in 70 years to be put to death in Georgia. Photo by Thomas Spink

“Vengeance and justice are two different ideas,” he said.

Bishop Wright said men and women behind bars are children of God and they have dignity behind bars. The fact that innocent people sit on death row should also caution death penalty supporters, he added. Bishop Wright said that inmates have been exonerated when DNA and other science prove the convicted did not commit the crimes.

The Death Penalty Information Center lists 161 people sentenced to death who were later acquitted of all charges related to the crime.

Two people connected to Kelly Gissendaner, a Georgia woman executed in 2015, sat on the panel. Gissendaner was the first woman in 70 years to be put to death in the state.

Norman Fletcher, retired chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia, said the death penalty is morally indefensible. Fletcher, who continues to serve as a lawyer in Rome, Georgia, retired in 2005 after serving for 15 years on the court.

“When people are informed, they understand it is an excess punishment. We have another way to do it,” he said.

Fletcher said Gissendaner’s role in the killing of her husband was not proportionate to her sentence, if the death penalty is reserved for the most heinous crimes. Her lover, Gregory Owen, committed the murder. He is serving a life prison sentence and will be eligible for parole one day, Fletcher said. Prosecutors made a deal to spare his life while committed to seek the death penalty against Gissendaner, he said.

Fletcher wrote to parole board asking to spare her life. At the time, he pointed out it would be the first time Georgia executed a person who didn’t actually kill another person since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976.

Lawyer Susan Casey, who represented Gissendaner and was present at her execution, said enough attention isn’t paid to redemption and forgiveness of inmates behind bars. She said an effort needs to be made to promote “restorative justice,” which can help victims and family members who have been harmed. This justice program focuses on rehabilitation through reconciliation with victims and the community.

“We can care for people on both sides of the human tragedy,” said Casey.