Athens

The transcendent power of art

By ELENA ACOSTA, Special to the Bulletin | Published March 31, 2022

ATHENS—The works of art were laid out in clusters on long strips of greenish cloth. Only a handful of students could claim a spot on the floor at a time. At the second or third round, I saw an opening and took it, my mind racing. I arranged my work. Then I stepped back—exposed, proud, yet terrified.

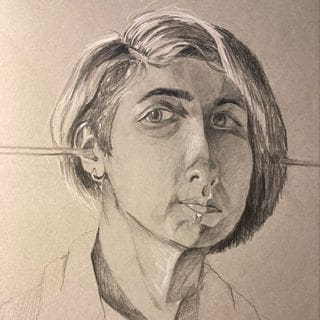

A self-portrait by Elena Acosta

Art is intimate, sometimes brutally honest. It is as if the painter rips out their internal organs and pins them to the wall for all to see. Perhaps that is why my heart becomes a jack hammer when I participate in peer critique.

According to the Orthodox icon painter, Father Anthony Salzman, art is a visual philosophy that tells us about reality in a personal way.

I met Father Salzman by chance one Thursday afternoon. He sat at a table on behalf of the Orthodox Christian Fellowship of the University of Georgia, quietly painting an icon of the Virgin Mary in the Tate Student Center. Father Salzman’s favorite thing about being involved in campus ministry is curious young people, students who approach with questions.

As Joey Martineck, former seminarian and now director of Respect Life at the Archdiocese of Atlanta, put it, authentic art expresses the deepest desires of the human heart.

“Part of the task of the Lord is to reveal us to ourselves,” he said.

In February, I chatted with Martineck, an actor and playwright, before he gave a talk on art and beauty at the Catholic Center at UGA.

In many ways Martineck and Salzman represent a contrast, participating in different religious traditions, working in completely different mediums and at different stages in life. Their words dance through my head, creating a dialogue between two people that, to my knowledge, have never met.

But there are commonalities. Each man’s story as a Christian artist includes beats which mirror each other. Both began creating as children. Both reached a moment of spiritual growth where they temporarily stepped away from art, unable to reconcile an artistic life with the life of a faithful Christian. Both experienced a resurrection of their talent with a newfound purpose.

Martineck returned to theater after studying St. John Paul II’s Theology of the Body and the New Evangelization. Father Salzman rediscovered art through icon painting.

“God baptized art and gave it back to me,” said the priest.

Even in their approach to the artistic process, Father Salzman and Martineck offer parallel wisdom.

Among Father Salzman’s paintings are a combination of stern icons and whimsical images. The “whimages” as he called them, represent the freedom of “learning to play.” Similarly, Martineck advocated focusing on the project that gives one the most joy and freedom.

In rare moments, artistic expression does more than reveal the artist’s insides. Sacred art, what Father Salzman calls “truly Christian” art, refers to culture, a time and a place and a stream of thought and understanding about reality.

“The beauty of iconography is we are not Xerox machines. We’re not scribes. We have to be baptized in the tradition, but we have to be present in the work,” Father Salzman said.

According to Martineck, the importance of sacred art, especially iconography, goes without saying, representing a different intentionality from secular art.

He adds, “I think all authentic art, everything that is truly beautiful, always has the capacity to lead us deeper into God.”

Martineck stressed art’s role in the New Evangelization and in advocating for human dignity. This means sharing the same message in new ways.

“We can get angry and we can shout at people…(or) lead with beauty and invite people in a way to mourn over what is happening,” he said.

Father Salzman also acknowledged the need to express faith through holy images in a way that this generation can hear. He said modernity is a part of tradition.

Some of Father Salzman’s work, including “Images and Whimages,” is on display at the Athens-Clarke County Public Library through May 8. A recording of his presentation conducted on March 12 was posted to the library’s YouTube channel.

Martineck expressed hopes of bringing his musical, “Garden,” to Atlanta. It tells the story of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace. The album “To the Dust” by Greg and Lizzy Boudreaux, which inspired the play, can be found on Spotify and wherever music is heard online.

Art is a bridge. East and West, the secular and the sacred, the past and the present, the material and the immaterial all converge in a burst of sights and sounds. For this 20-year-old cradle Catholic, creativity has served as the path from the frustrations and anxieties of ordinary life to the moments of transcendence, the glimpses of the deeper truth that makes ordinary life worth living.

This story is part of Young Adult Angle, content by and for young adults. To write for this regularly featured section, email Samantha Smith at ssmith@georgiabulletin.org.