Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderMarietta

Atlanta priests serve as ‘physicians of souls’ during COVID surge

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published March 18, 2021

MARIETTA—Personal protection equipment, gloves and mask became like the vestments for Father Bryan Kuhr to share God’s graces with the ill.

“I am reminded that I am a physician of souls, bringing the mercy of God,” he said.

Father Kuhr was one of a handful of Atlanta priests who stepped forward to serve patients hospitalized with COVID-19. He stood at countless bedsides at Wellstar Kennestone Hospital, in hospices and in homes visiting people in need of anointing of the sick or the last rites.

This ministry offers peace to those dying and comfort to those lonely, separated from loved ones and religious communities because of the virus.

Initially in the pandemic, Father Kuhr remembered being concerned as life paused and public Mass and administering sacraments were suspended. His ministry from St. Joseph Church, Marietta, grew from a desire for the ill and dying to receive the consolation of the final sacraments of the church. Older priests or clergy with health problems might be wary of catching the virus, but the 40 year old figured since he was young, he’d fare better if sick. He has not gotten ill, he said.

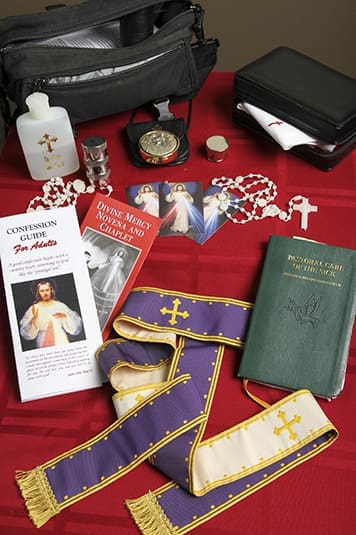

The religious contents found in Father Bryan Kuhr’s anointing bag are displayed on a table. These items are carefully stored in the anointing bag, top left, when he makes hospital visits. Photo By Michael Alexander

Through the layers of required protective gear, Father Kuhr hoped the patients would know “the mercy of God, and the peace of Christ, so they can be at peace, knowing they’re going to go before the Lord with a clean soul.”

Preparing for death in life

This pandemic upended much of life. Hospital staff were challenged to balance patient wellbeing, community health and spiritual needs. Chaplains who once held hands with hospitalized patients were suddenly only permitted to stand at a distance or kept out of rooms when medical equipment was rationed.

For Catholics unable to receive last rites, the power of prayer and striving to live as a Christian prepares people to meet God also, said one theologian.

Believers who fostered a relationship with God, through Mass and the Eucharist, and tried to live the Gospel have been preparing for death. The sacrament is not a requirement for Catholics, said Sister Judith Kubicki.

“There is a power to the prayer of the church and every single member of the church, whether or not they are in person with the person who was dying, there is still a power, we believe, to prayer,” she said.

The sacrament administered by priests and known as last rites is three parts: anointing with the oil of the sick, penance and viaticum—“the Eucharist on the way (to eternity),” she said.

Sister Kubicki, a professor emerita and sacramental theologian at Fordham University, said the rite is for the church to accompany believers “as a mediator of grace in a person’s time of need.”

“The first purpose of the sacrament is to give people a sense of strength and peace and courage,” said Sister Kubicki, a member of the Felician Franciscan Sisters of North America.

Hospital rooms as sacred places

Father Michael Metz remembered the sacredness of the hospital rooms.

From the hustle to get into scrubs, he walked into rooms filled with the noise of the heart monitor, oxygen and other devices that kept the patient alive.

“This is the doorway right here in between life and death and so you’re kind of on the edge of people’s time here on earth,” he said. “It’s clearly some sort of a dangerous place. And yet Jesus is going to be here.”

Father Metz, 31, visited Catholics when he served at St. Mary Church, Rome, at Floyd Medical Center and Redmond Regional Hospital. He is now living and serving in Peachtree City at Holy Trinity Church.

He started visiting people in April, moving into his own living quarters to keep others safe. He talked about the power of touch, and sharing the moment in the presence of others. People die alone during these COVID times, he said, and “that seems to me like the most horrible thing that you could do.”

About a half mile from Father Kuhr’s parish is Wellstar Kennestone Hospital.

He lives in another house on the parish grounds to limit exposure to other members of the parish staff. In May his ministry began. At the peak, Father Kuhr said he’d get three to five calls a day from families or the hospital.

Father Michael Metz, parochial vicar at Holy Trinity Church, Peachtree City, has visited Catholic patients in the hospital during his current assignment and his previous assignment at St. Mary Church in Rome. Photo By Michael Alexander

The 633-bed Marietta hospital had nearly one in three hospital beds filled with patients battling the virus, with some 39 percent of intensive care patients testing positive for the virus, reported The COVID Tracking Project at the end of February. The virus killed nearly 900 people, stated the Cobb County Public Health Department.

In March 2020 in the face of the unknown virus, the hospital limited access to patients. The ministry of Father Kuhr aided families and medical staff by bringing comfort.

“During times when our COVID-19 cases have surged there has been a huge increase in patients who are feeling scared, and it is often during these times that patients turn to their faith to provide comfort and guidance. Working with community clergy like Father Bryan has been an extremely important way to provide support to the large number of Catholic patients who choose Kennestone for their medical care,” said a statement from Wellstar Health System.

“His presence has been appreciated, and we are thankful for his willingness to offer blessings and sacraments during such difficult times,” said the statement.

Some medical workers were surprised to see him close to patients during visits to the dying, he said. However, a video call or standing outside a room wasn’t enough for his needs. A priest draws close to patients to hear confession, bless them with the oil of the sick, and to offer Communion, he said.

He hoped to get to patients in the intensive care unit before they were sedated and intubated. The sacraments are for the living not the dead, he said. “They were high risk. They’re going on the ventilator, so they’re probably not going to come off.”

However, an unconscious person on a ventilator isn’t unaware, he said. Hearing is thought to be the last sense, Father Kuhr said, so even to the sedated he offered the ministry of the church.

“You are having a conversation with the person,” said the priest.

He says into their ears, “The God who loves you, the God who created you, the God who redeemed you desires to forgive your sins now and give you his mercy.”