With assistance from friends, El Refugio opened as a hospitality house in 2010 in southwest Georgia's Stewart County, under the direction of Amy and PJ Edwards, members of St. Thomas the Apostle Church, Smyrna. Photo By Michael Alexander

Lumpkin

Detainee families find comfort and support at El Refugio

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published April 14, 2016 | En Español

LUMPKIN—Inside this cozy yellow bungalow, the kitchen smells of fried chorizo, onions and peppers, and scrambled eggs. A fresh pot of coffee is ready by 7 a.m. as guests awaken in the three bedrooms.

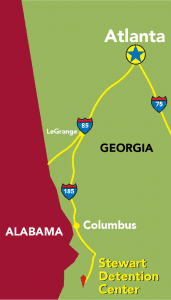

A mile from the barbed wire surrounding Stewart Detention Center in rural southwest Georgia sits this house of hospitality with its small front porch. Family members who drive hundreds of miles to spend one hour visiting detainees at the center can find comfort and rest here. The plainly furnished house is known as El Refugio (“the shelter”).

After a brief stopover at El Refugio, Sandra Portillo, foreground, stands with her mother and daughter as they prepare to return to the Charlotte, N.C., area. Portillo and other family members made the six-hour drive to visit her husband, who has been detained at the Stewart Detention Center for a year and a half. Each detainee gets one hour-long visit per week. Photo By Michael Alexander

On a recent weekend, 30-year-old Sandra Portillo drove from North Carolina, leaving the family home at 4 a.m. She visited her detained Mexican husband, who has been held for a year and a half, for an hour, she said. She stopped for a lunch of grilled cheese sandwiches and soup at El Refugio before the next six hours on the highway. Her three tykes ran around the grassy yard. It was her second visit to El Refugio, which has lifted the loneliness of a detention center visit, said Portillo.

“I feel this was family. They were really helpful,” she said. “We could come here and rest for a little while.”

Without El Refugio, Melissa Sandoval and her granddaughter faced a night sleeping in her truck.

Sandoval, who lives in Rome, drove from there for the weekend in Lumpkin. They visited her husband, an undocumented immigrant native of Mexico. She said he was taken into custody on a traffic stop.

After a night’s sleep and breakfast at the shelter, she said, “Now, I feel so blessed.”

More than 1,700 immigration detainees held

What draws family members to this rural city is the privately run, medium security Stewart Detention Center. It is one of more than 250 immigration detention centers in 28 states, according to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The private Corrections Corporation of America manages the facility. It has beds for 1,752 men. Rules allow visitors to see detainees for one hour a week. A plexiglass barrier separates them from their loved ones as they talk over a phone.

What draws family members to this rural city is the privately run, medium security Stewart Detention Center. It is one of more than 250 immigration detention centers in 28 states, according to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The private Corrections Corporation of America manages the facility. It has beds for 1,752 men. Rules allow visitors to see detainees for one hour a week. A plexiglass barrier separates them from their loved ones as they talk over a phone.

Activists have complained about Stewart. The Southern Poverty Law Center filed concerns with government officials over how practices there interfere with detainees’ access to lawyers. Legal representation can have a critical effect on detainee cases. According to the SPLC letter, dated March 21, 21 percent of immigrants with lawyers have success in immigration court nationwide versus only 2 percent who are unrepresented.

This road leads up to the Stewart Detention Center, off to the right, in Lumpkin. It has a capacity for approximately 1,750 detainees, but the exact number of men being held is not known at the moment. Photo By Michael Alexander

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement spokesman Bryan Cox rejected the claim about lack of legal access. “As a matter of policy attorneys are allowed access to their clients in ICE detention. Any claim to the contrary is something we’d categorically dispute,” he said in an email.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia in 2011 raised concerns about detainees facing abuse of authority, lack of access to lawyers, and about transferring detainees to a remote area of Georgia, away from family support.

Nearly 205,000 parents of U.S.-citizen children were detained and deported between July 2010 and October 2012, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Office of Migration Policy.

To supporters, El Refugio is a Christian response to serve the wives, children and loved ones of the detainees, whose immigration status in the United States is in question. Some entered without documentation. Others have overstayed after entering legally while some face deportation after committing a crime. They await an appearance in immigration court or deportation.

Moments before this photo, El Refugio guests (l-r) Hailee Norton of Rome, 6, Jafet Martinez of Queens, N.Y., 9, his brother Jared, 5, and his sister Brianna, 8, were running around and playing in the yard. At that moment the issue that briefly brought them together was either unspoken or incomprehensible, for they were merely conducting themselves as innocent children. Photo By Michael Alexander

To their families, home is the word used to describe this one-bathroom refuge, where a crayon drawing of a tree filled with birds is taped to the refrigerator. Walls are covered with pictures drawn by a child’s hand and framed letters of thanks written by families. Kids pull out the Etch-a-Sketch toy. The large backyard draws most of the youngsters for games of chase and soccer. The three bedrooms are filled with bunk beds with room to sleep nearly a dozen. Families are not expected to pay for their overnight visit, although some slip the coordinators a few dollars.

Marilyn McGinnis is a member of the Atlanta Mennonite Fellowship. She travels to Lumpkin about every six weeks to serve as a host at El Refugio.

“It’s a tangible way to make a difference on an issue (people) feel passionate about, but also feel powerless to change,” she said, adding this service makes a difference in the lives of people going through a crisis.

“Each weekend leaves me emotionally drained and physically tired, but the opportunity to serve neighbors in a time of need is extremely rewarding,” said Kimberly Nigro, who lives in Chamblee and attends Atlanta Christian Church. A former missionary in El Salvador, Nigro heard “countless stories” of individuals risking safety to come to the United States, she said.

“I was moved by the idea of a ministry of hospitality and visitation as a way to ‘welcome the stranger’ despite our nation’s unwelcoming policies,” she said.

El Refugio leaders inspired by Catholic social teaching

Sitting among a group of people in the El Refugio living room, co-founder PJ Edwards, right, conducts an orientation regarding what to expect when they visit some detained men inside Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin. Photo By Michael Alexander

The doors opened in 2010. Inspired by the JustFaith program and Catholic social teaching, PJ Edwards and his wife, Amy, simplified their life dramatically. Along with that, the couple helped to start El Refugio.

PJ left a white-collar management career track and dedicates his time to nonprofit and advocacy work. Edwards joked he now uses his “evil business skills for good.” Amy continues her corporate consulting job. The couple, both 45, and members of St. Thomas the Apostle Church, in Smyrna, have two children.

What fuels their mission is the church’s stance on human dignity. Catholic social teaching’s core principle is every person is created in the image of God and therefore is invaluable and worthy of respect, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

“Walking with these families, they are some of the bravest, most courageous people that we have met. It has really been a gift for us to be a part of it,” said Edwards.

The couple drives the nearly 150 miles south from Atlanta to serve as coordinators of the house several weekends a year.

A group of eight University of Georgia students and a family of three prepare to drive over to the Stewart Detention Center, Lumpkin, to visit with some detained men. Photo By Michael Alexander

Many detainees are sent to Stewart from faraway states to fill beds. El Refugio maintains a long list of detainees who have no regular visitors and directs a steady flow of students and faith-based groups to talk with those without family nearby.

The house runs on donations to cover its $800 a month cost of rent and utilities, mostly from other graduates of the JustFaith program. Volunteers prepare meals and snacks for the families. Grants complement the aid from individual donors, including from Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services, the American Immigration Lawyers Association, CIVIC, and the Catholic Foundation of North Georgia, said Edwards.

In 2014, the house welcomed nearly 200 overnight guests. The organizers facilitated 342 visits to 152 different detainees, according to Edwards. It was done with the help of 335 volunteers willing to serve.

The only certainty about a weekend here is the unknown. A small billboard at the entry of the detention center could catch a visitor’s eye and they will show up or people make plans to stay here but don’t come. The house and its volunteers stand out from the crowd.

“It is such an unusual thing—people just offering Christian hospitality, particularly these white faces—to these people that all they hear on the news is how much Americans hate them and they are unwelcome here and we’re going to build a wall,” said Edwards.

El Refugio overnight guests (l-r) Melissa Sandoval and her granddaughter Hailee eat breakfast along with additional guests Jared Martinez, his brother Jafet, his father Milber, and his sister Brianna. Melissa drove from Rome to visit her husband at the Stewart Detention Center. Milber drove his family down from Queens, N.Y., so his wife Debora could visit her brother. Photo By Michael Alexander

For Amy, the effort is being present to people, with an open door and food at the ready.

“There is not a lot I can do. I can’t create the miracle. I can’t fix or change massive systems that exist within the United States, and that we need to all talk through, but I can be there for another human being,” she said.

The service isn’t always easy. She said for about a year she felt annoyed about waking up at 6 a.m. on weekends to drive three hours, but “then there is this great peace.”

Six years on, the detention center remains open. Edwards isn’t discouraged because faith at times demands sitting with people.

“It is frustrating that things don’t progress as quickly as I would like them to, but at the same time, it is part of our practice, it is part of our faith practice to come here and be present,” he said.

“It is really practicing and exercising your faith,” said Edwards, “to bring these values out of Smyrna, out of our house, and to try and practice them here.”

Around El Refugio’s large table, a family from New York City is eating breakfast. Debora Calderon, her husband, and three kids pack up the pickup truck. They drove for 18 hours the day before to visit her teenaged brother, a native of Honduras, for one hour. They will visit again for another hour before driving back up the East Coast to their home. Calderon is able to stay in the United States with what is called temporary protected status because of the damage caused by Hurricane Mitch to her country. She said her brother fled Honduras more recently because gang members showed up at their mother’s house and he also received threats from the police.

“We try to do the right way, but it’s not possible,” she said.

It’s her family’s second visit to El Refugio. She said, “God is good. In a bad situation, somebody is doing good.”

For information on the ministry, visit elrefugioministry.org.