Washington

Templeton winner hopes L’Arche communities ‘may become sign of peace’

By NATE MADDEN, Catholic News Service | Published March 20, 2015

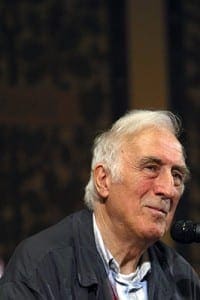

WASHINGTON (CNS)—Jean Vanier, a Catholic author and theologian who founded L’Arche, an international network of communities where people with and without intellectual disabilities live and work together, has won the 2015 Templeton Prize.

L’Arche is dedicated to the creation and growth of communities, programs and support networks for people with intellectual disabilities across the globe.

The movement began quietly in northern France in 1964, when Vanier invited two intellectually disabled men to come and live with him as friends, and has grown to include 147 L’Arche residential communities in 35 countries, and more than 1,500 Faith and Light support groups in 82 countries that similarly urge solidarity among people with and without disabilities. In 2012, L’Arche Atlanta opened a home in Decatur.

The announcement was made at a news conference March 11 at the British Academy in London by the John Templeton Foundation, based in West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania.

Valued at about $1.7 million, the prize is a cornerstone of the foundation’s international efforts to “serve as a philanthropic catalyst for discoveries relating to human purpose and ultimate reality.”

Each year it honors “a living person who has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s breadth of spiritual dimensions, whether through insight, discovery or practical works.”

Previous recipients include Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Dalai Lama and Blessed Teresa of Kolkata.

In his address to the media, Vanier called for a “deeper unity of all people” to cope with a world that is both “evolving rapidly” and “in crisis,” but also cited much-welcomed change: “Change is gradually taking place, like a little seed in fertile earth, a seed of peace.”

“There is also a change in the way people with intellectual disabilities are seen,” he continued. “For many years these wonderful people were seen as ‘errors,’ or as the fruit of evil committed by their parents or ancestors. … They were terribly humiliated and rejected. Today we are discovering that these people have a wealth of human qualities that can change the hearts of those caught up in the culture of winning and of power.”

Vanier, 86, was born in 1928 in Geneva, the fourth of five children of Canadian parents, Maj. Gen. Georges and Pauline (Archer) Vanier. His father was a highly decorated soldier in World War I and later a diplomat who served as first secretary in the High Commission of Canada in London and as Canadian ambassador to France.

Georges Vanier also was governor-general of Canada after being appointed by Queen Elizabeth II in 1959. He served until his death in 1967.

Vanier lived in England, France and Canada, receiving a broad education in English and French. After eight years in the Royal and Canadian navies and intense meditation and prayer, Vanier decided to devote himself to pursuits of the mind and spirit.

He resigned his naval commission in 1950, and from 1950 to 1962 devoted himself to spiritual and theological studies and inquiry. He earned his doctorate in 1962 from the Institut Catholique in Paris with a widely praised dissertation, “Happiness as Principle and End of Aristotelian Ethics.”

“I’d left the navy to follow Jesus, didn’t know where or how,” Vanier told Catholic News Service in a telephone interview from London. “Then one day I went to meet my spiritual father, who was a chaplain at an institution for the disabled.” There he saw the reality of “the whole world of people with disabilities, humiliated and depressed” and felt the need to do something.

“I had never even imagined that people were being treated like that,” he recalled. “I just felt that I should do something … the only thing I could do was maybe welcome two.” So he did.

“I bought a house, got permission from the French state” and took in two men. One was named Rafael, who could only say a few words, another, Philip, a victim of encephalitis who had a “few intellectual disabilities.”

For Vanier, this was simply “meeting a situation of horror and saying, ‘What could I do? Both had parents who had died, so this seemed like the best way to help them.’”

Vanier has traveled extensively throughout the world to establish and support L’Arche and Faith and Light communities, to give talks, lectures and retreats, especially to young people and those at the margins of society, including in prisons.

Vanier is also the author of more than 30 books, including the bestseller “Becoming Human,” all of which have been translated into 29 languages.

In his remarks at the news conference, Vanier recalled the story of a young woman he encountered in L’Arche’s early years named Pauline. “She came to our community in 1970, hemiplegic, epileptic, one leg and one arm paralyzed, filled with violence and rage. … Our psychiatrist gave us good insight and advice: Her violence was a cry for friendship.

“For so long she had been humiliated, seen as hardly human, having no value, handicapped,” he continued. “What was important was that the assistants take time to be with her, listen to her and show their appreciation for her. Little by little she evolved and became more peaceful and responded to their love. Her violence disappeared … she loved to sing and to dance.”

“It takes a long time to move from violence to tenderness,” stated Vanier, but “the assistants who saw her initially as a very difficult person, began to discover who she was under her violence and under her disabilities. They discovered that for a person, growth was not primarily climbing the ladder of power and success, but of learning to love people as they are.

“Love, in the words of St Paul, is to be patient, to serve, to bear all, to believe all and to hope all.”

According to Vanier, L’Arche and Faith and Light are “like an immense laboratory. … They are places of healing of rifts and of hearts where all become more human.”

Vanier hopes that with the Templeton Prize his organizations and others like them can “create spaces and opportunities for such meetings, meetings that transform hearts.

“Places where those caught up in the world of success and normality … come together … places where they can share together, eat together, laugh and celebrate together, weep and pray together. … Here we may become a sign of peace.”