The MLK Youth Celebration, held Jan. 18 at St. Peter Claver Regional School, ended with a final blessing from Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory and the singing of “We Shall Overcome” by the assembly. Attending the celebration were Charles O. Prejean, second from left, retiring director of the Office for Black Catholic Ministry, Archbishop Gregory, second from right, and Diane Starkovich, Ph.D., right, superintendent of Catholic Schools. Photo By Lee Depkin

Reflections on nonviolence in Atlanta’s Catholic community

Published January 22, 2015

Given the violence of this era, what does the previous generation need to communicate to the next about nonviolence as a means of social change?

That was the question posed by The Georgia Bulletin as the community marked the 2015 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration.

Responses from six local Catholics appear below. They range from people who’ve spent decades in ministry to a high school student voicing a desire to build on the sacrifices of generations who came before her.

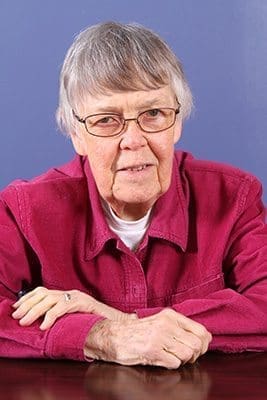

SISTER MARIE SULLIVAN, OP:

“I feel like everything needs to slow down a little bit. We have to look at what is really happening to us right now.

“The technical part of communication has really moved. It seems like everything has to be done immediately.

“But does the present generation even know about what Martin Luther King really thought? Do they know what it was like for the young people to sit at these lunch counters (to end segregation) and be pushed and punched in the back and not hit back? Those young people knew what they were doing.

“That seems so foreign to the culture right now.

“How many of our kids even know what the practice of nonviolence is and who pushed it along the way? Visiting the (Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta), they make you feel like you were right there at that lunch counter.

“I think if we could really get the young people to see that nonviolence doesn’t mean we accept what’s happening. It means we don’t answer it with violence. Answering violence with violence never worked out.

“Young people have to see examples. The examples they see now aren’t worth anything. They have nothing to stand on. Who’s a real figure for young people? The news media lots of times also only portray youths doing wrong things. We don’t see youths being honored, especially those who are from lower classes.

“I’m an optimist. You have to have something inside yourself to give to others.

“Sometimes we want things without paying the price. The civil rights people paid the price and I’m wondering if we, as a nation, have paid the price. People don’t realize—this is real. This happened. People gave their lives for these things and what are we willing to give to pass it on?

“We need to have a great love for what we are doing. There has to be a passion that comes out, which does come out if we are ready to listen. We have to get back to seeing where we are going.

“How can we get people really excited about being able to help another person? Even children can be shown.

“We need to create the environment this can come out of—a good environment. When we see on television a person being beheaded, violence is raised up.

“Violence to one another is not the same as suffering for a cause.”

Sister Marie Sullivan, a Sinsinawa Dominican sister, has been ministering in the inner city of Atlanta for about 35 years, including founding a center to teach job and life skills to those struggling to get out of poverty. Her vision has been to give people tools to build a better life, to ask them to share in finding solutions to their problems, and to support their efforts with all her might. In 2012, the Sullivan Center became part of the Society of St. Vincent de Paul Georgia. She is active at Our Lady of Lourdes Church, Atlanta.

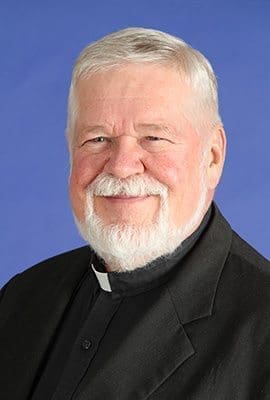

MSGR. HENRY C. GRACZ:

“Ten years ago, an interfaith group from Atlanta joined the international Jewish community in their annual spring visit to the Nazi death camps in Poland. I can’t help but reflect on that trip as one of the most painful and profound experiences of my adult life, calling out a demand to burn out anger and hatred within me. It was striking how that annual trip is designed to take Jewish youth to experience the tragic reality of humanity’s brutality and hatred when we have lost focus on our dignity as God’s children. Nothing can extinguish our hope.

“To my mind there are two powerful connections in our challenge to pass on and re-create the vision of nonviolence:

“Sadly, we need to never forget the past. Its painful reality drove and motivated the leaders of the nonviolent movement. “Never again” has to spring from the depths of our hearts.

“A further connection comes from our faith, deep in our being. Our loving God gives us hope. He still impels us to move ahead with a healing love. I often think that healing is a powerful charism of the Catholic community today. We’ve seen it when Pope John Paul embraced his would-be assassin. We’ve seen it when missionary women and men embrace the poor in Latin America. We’ve seen it when Pope Francis embraces the Buddhist, Muslim and Jew as family. This spirit of forgiveness and service brings about a healing vision.

“Our world, God’s world, can become better than it is. This vision binds us to one another as living tools of God, carrying his message in this world. Living not for ourselves, but for others.

“Our message to those who carry the torch of nonviolence to this age: never forget how weak we can become, but how strong we can be in God’s limitless love.”

Msgr. Henry C. Gracz is the pastor of the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Atlanta. He has served in the archdiocese since the 1960s, coming into the priesthood during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. His pastoral endeavors have emphasized ecumenism and racial and social justice.

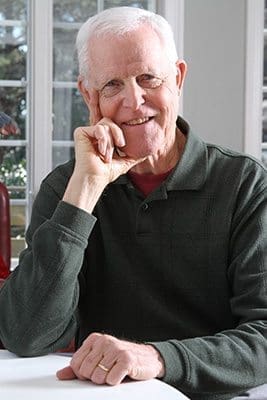

JOE GOODE:

“Nonviolence is a subject that has been very important to me over the last 30 years or so. I think the seeds leading to my conviction that nonviolence is the path I want to follow were planted in preparing lesson plans for fifth-grade CCD at St. Jude Church. I began reading the New Testament in earnest for the first time. Years later, following a parish retreat and a Cursillo weekend, I came to an epiphany moment that there is no justification for violence based on the life and teachings of Jesus. In 1985 I made an entry in a logbook I kept at my office that I no longer believed that violence of any kind could be justified. I have never retreated from that position.

“Pax Christi (Latin for the Peace of Christ) was founded in France in 1945 by a group of Catholics in the aftermath of World War II where French Catholics and German Catholics, who professed the same faith and celebrated the same Eucharist, had killed each other by the hundreds of thousands. They thought this could not possibly be the will of God and they began meeting to pray for forgiveness and reconciliation. Pax Christi International evolved out of those meetings and spread across Europe. In 1952, Pope Pius XII declared Pax Christi to be “the official international Catholic peace movement.” It is now active in 50 countries, including the United States, where it began in 1972. Pax Christi USA has as its primary mission working to create a world that reflects the Peace of Christ by exploring, articulating and witnessing to the call of Christian nonviolence.

“The Catechism of the Catholic Church presents two paths for addressing conflict—“nonviolence” and “just war.” The “just war” tradition allows for the use of violence under specified conditions. The “nonviolence” tradition rejects the use of violence under all conditions. The Church teaches that one can take either path and remain faithful to Jesus. The vast majority of Christians accept the just-war path as being the only practical way to peace. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was not on the side of the Christian majority. He came to believe that nonviolence was the only acceptable path for a Christian, something that required extraordinary courage. Nonviolent resistance as used by Gandhi and King proved to be successful in bringing about meaningful social change. There are many, many examples of the success of nonviolent movements across the world.

“We do not hear much in our church about these nonviolent success stories, nor do we study and talk about the teachings of Jesus with respect to the use of violence. Young people are smarter than we think, and they need to hear more from the older generation and from their spiritual leaders that they have a choice with respect to the use of force.

“Nonviolence should not be swept under the rug as an unrealistic and ineffective strategy. It is neither. For me it is clearly the way of Jesus and the only way to peace.”

Joe Goode, a retired civil engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, grew up in Atlanta and attended Christ the King School, Marist and Georgia Tech. He and his wife, Mary Jean, have six adult children and eight grandchildren. They are parishioners of St. Jude the Apostle Church, Sandy Springs, and co-leaders of the Pax Christi chapter at St. Jude, formed in 2005. They were members of Pax Christi Atlanta from 1991-2005. Pax Christi young adult members are planning a conference on nonviolence in May.

BEATRICE PERRY SOUBLET

“It is important that we recognize that nonviolence is more than a strategy to be used as a means of social change. Nonviolence must be a way of life.

“In a country that worships at the unholy altar of violence, we are surrounded by images of violent behavior. Violent terms and metaphors adorn our speech like so much cheap jewelry. Let me give you some examples. The character in a movie or drama who wins the day often has the most powerful weapon. Not often is the victor of a battle, be it verbal or physical, the person that is the wisest, most modest or nonviolent. Loud offensive speech, peppered with obscenities, is the model that our young people see as an appropriate and effective conflict resolution strategy. Our language is replete with words and images that refer to violence. “Bullet points,” “killing two birds with one stone,” “beat you to the punch,” “I’ve got you in my sights,” “shoot you an email,” are all expressions that incorporate violent language. We use them and many others without even thinking.

“Nonviolence is counter-cultural. It runs against the grain. It strikes us as weak, ineffective, even cowardly.

“How, then, and why do we pass on this way of life to a new generation? When I was in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s we were taught during the sit-ins not to respond with anger no matter what the white people did to us. We were to sit and be peaceful and nonviolent. All persons trained to participate in acts of civil disobedience were taught this strategy. Imagine what would have become of the movement had we done otherwise.

“We must teach our new generation two important lessons. First they must examine their behavior and their language and intentionally expunge any references to violent acts. Think before acting or speaking in anger. Second, as participants in movements for social change, the only appropriate strategy is nonviolence. Too many nonviolent persons in previous generations have risked and even lost their lives for the cause of justice. Their memory cannot be dishonored by any destructive acts. The cause will not be won by violent acts.

“Nonviolence is a way of life. Nonviolence is a way of thinking. Nonviolence is a way of speaking.

“Nonviolence is a way of acting. It is the only peaceful route to social change.”

Beatrice Soublet participated in sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1962 when she was a sophomore at Bennett College there. She was class valedictorian and holds a master of arts in teaching from Georgia Washington University. A native of New Orleans, she taught public elementary and middle school and was a Catholic school principal. She and her husband, Lawrence, relocated to Atlanta following Hurricane Katrina. She is a volunteer tutor and founding member of ERACE, a discussion group that helps to eradicate racism. ERACE meets on the second and fourth Saturdays at Our Lady of Lourdes Church, Atlanta, at 11:15 a.m.

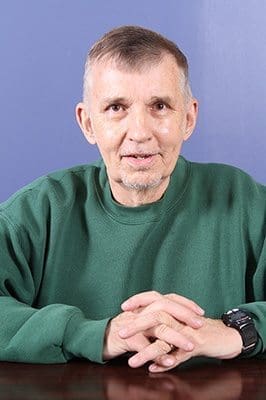

RON CHANDONIA:

“Who does the term “nonviolence” bring to young people’s minds? Gandhi? Dr. King? Maybe Jesus?

“Perhaps, but the most honest among them, I believe, are more likely to picture Mr. Van Driessen, the mealy-mouthed peacenik teacher whose finger-wagging idealism proved helpless in reaching MTV’s Beavis and Butthead: “C’mon, guys, please!”

“Too many kids see nonviolence as ineffectual weakness because that is mostly how their elders see it, including those raised on the Sermon on the Mount. An adult catechist once rebuked me: “Preaching nonviolence is OK, but there are really bad people out there who want to kill us, and we have to kill them before they do.” How sad, I replied, that Our Lord had failed to share such wise advice.

“But sarcasm does not win minds or hearts. Witness does. And the witness of nonviolence is not passivity in the face of evil. As my friend Father Jim Burtchaell wrote in “Philemon’s Problem,” conscientious objection “is not being a passive spectator. It is actively objecting: to the use of force, but firstly to the outrages that tempt good people to take up arms. It is not a safer alternative, because conscientious objection is at least as dangerous as military service.”

“Examples abound in our history—from Francis of Assisi slipping behind the Crusaders’ lines to embrace the Egyptian sultan to Franz Jägerstätter sealing his death warrant by refusing service in Hitler’s army. Though Francis is a beloved saint and Jägerstätter has been beatified, Catholics today might be surprised or even baffled to learn the details of their lives.

“To inspire our young people to break the cycle of violence in our own time, we need to tell such stories more often, including stories of those saints among us who have not yet been canonized, like my fellow parishioner at Our Lady of Lourdes, Michael Vosburg-Casey. Though he came from a privileged background, Mike became a Jesuit volunteer committed to serving Atlanta’s marginalized. As a result of his nonviolent witness against Fort Benning’s School of the Americas, he served six months in federal prison. That experience gave him special empathy with street people who had also done jail time, and Mike got to know many of them personally. He considered it important not only to learn the names of the people he encountered on the streets but to listen attentively to their stories, even the most implausible stories, so that he could ask thoughtful questions about their lives when they met again.

“When Mike died of cancer in the summer of 2013, his funeral was packed with people who do not often come into a Catholic church, or into any church, including young people who had seen in Mike, up close and personal, the face of nonviolence. All of our young people should see that face, up close and personal.”

With bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Notre Dame University and a doctorate from Emory University, Ron Chandonia taught for 25 years in Atlanta’s inner city and now offers several courses in the archdiocesan diaconate formation program. He is a longtime advocate of the Church’s consistent life ethic. He and his wife, Charlene, are members of Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Atlanta; they are parents of two grown sons and two teenagers.

CAMRYN SMITH:

“World peace cannot be obtained without the work and agony produced by the ones who have paved the road ahead of us. Our ancestors. We have a long way to go, but it is not impossible. Those people, who are written in our history books, including the ones who go unmentioned, fought for the future, for our future.

“And now we fight for the future of those who are to come ahead of us. How? The words we speak, our actions and reactions, and most importantly, hope for the future. Kindness is not simply an action, it can be a series of words that may have the most simple of meanings, but a great response. We fight, but this fight has become physical and has been destroying people’s lives. Every life on this earth has its own unique importance. No one should care about the background of a particular person. Black, white, red, yellow, we are all people of God. We are people of the people and yet many choose to destroy each other. Our actions and reactions have to be for peace.

“Peace is a loose term and greatly used, but it cannot simply be spoken. Peace needs to be used as an action. If one were to look closely, amity could be seen everywhere. We do not have to physically fight for peace. Let us fight for nonviolence with nonviolence. As Martin Luther King Jr. eloquently put, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” Throw fire onto an already burning bush and the flames will seek greater heights.

“This world has already gone through copious changes, but there is more to be done. Perhaps this strive for harmony will never cease. Martin Luther King Jr. and many others have gotten the ball rolling, and now it is in our court. It is our turn. Nonviolence can be used to help many people and many poor situations. Socially, our world is corrupted. There is much conflict between races and various groups of people.

“Acceptance. One word. It is a personal action to be OK with the way people are. As a community, we could truly work on acceptance. Is that not what people have been fighting for, is that not what peace is? We must accept each other and this world we live in. Nonviolent actions for peace have been going on for quite some time. Though it seems nothing has changed, much has. We cannot quit. Those who have passed before us did not quit. So let us not quit on the ones who come in the future. Allow the message of peace to live on throughout the generations. Let us shape this world into what God created it for in the first place. A place to love Him and to love each other.”

Camryn Smith is a sophomore at St. Pius X High School, Atlanta. The daughter of Vincent and Mardessa Smith, she attends St. Thomas More Church in Decatur.