CNS photo/Paul Haring

CNS photo/Paul Haring Vatican City

Pope beatifies Blessed Paul VI, the ‘great helmsman’ of Vatican II

By FRANCIS X. ROCCA and CINDY WOODEN, Catholic News Service | Published October 30, 2014

VATICAN CITY (CNS)—Beatifying Blessed Paul VI at the concluding Mass of the Synod of Bishops on the family, Pope Francis praised the late pope as the “great helmsman” of the Second Vatican Council and founder of the synod, as well as a “humble and prophetic witness of love for Christ and his church.”

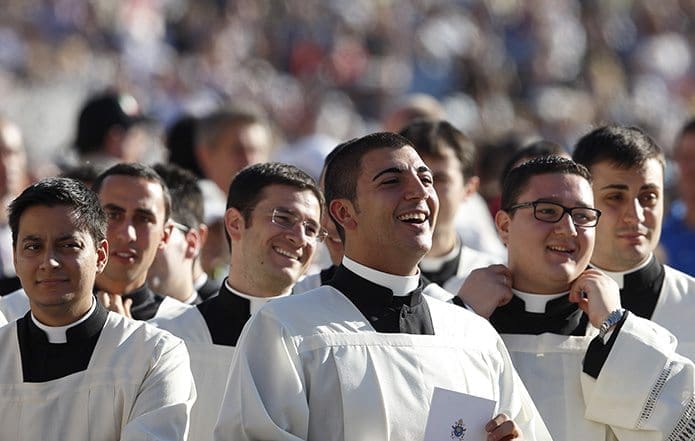

The pope spoke during a homily in St. Peter’s Square at a Mass for more than 30,000 people, under a sunny sky on an unseasonably warm Oct. 19.

“When we look to this great pope, this courageous Christian, this tireless apostle, we cannot but say in the sight of God a word as simple as it is heartfelt and important: thanks,” the pope said, drawing applause from the congregation, which included retired Pope Benedict, whom Blessed Paul made a cardinal in 1977.

“Facing the advent of a secularized and hostile society, (Blessed Paul) could hold fast, with farsightedness and wisdom—and at times alone—to the helm of the barque of Peter,” Pope Francis said, in a possible allusion to “Humanae Vitae,” the late pope’s 1968 encyclical, which affirmed Catholic teaching against contraception amid widespread dissent.

The pope pronounced the rite of beatification at the start of the Mass. Then Sister Giacomina Pedrini, a member of the Sisters of Holy Child Mary, carried up a relic: a bloodstained vest Blessed Paul was wearing during a 1970 assassination attempt in the Philippines. Sister Pedrini is the last surviving nun who attended to Blessed Paul.

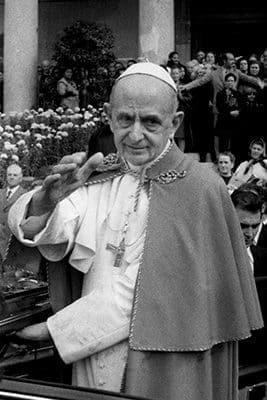

Pope Paul VI greets the crowd as he visits the Verano cemetery in Rome in 1973. CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photo

In his homily, Pope Francis did not explicitly mention “Humanae Vitae,” the single achievement for which Blessed Paul is best known today. Instead, the pope highlighted his predecessor’s work presiding over most of Vatican II and establishing the synod.

The pope quoted Blessed Paul’s statement that he intended the synod to survey the “signs of the times” in order to adapt to the “growing needs of our time and the changing conditions of society.”

With Pope Paul’s beatification, the 50th anniversary of the publication of his first encyclical letter, “Ecclesiam Suam,” and the 36th anniversary of his death Aug. 6, 1978, became the occasion for multiple reflections on his life and legacy in the Vatican media.

“Although he was not always understood, Paul VI will remain the pope who loved the modern world, admired its cultural and scientific wealth and worked so that it would open its heart to Christ, the redeemer of mankind,” wrote Cardinal Giovanni Battista Re.

The Italian cardinal, a former papal diplomat like Pope Paul, said that while St. John XXIII is remembered for having convoked the Second Vatican Council and presiding over its first session, it was Pope Paul who was the “real helmsman of the council,” presiding over the last three of its four sessions and guiding its implementation.

Both Cardinal Re and Pope Francis repeatedly refer to Pope Paul as a man sensitive to the problems and anxieties of modern men and women, a sensitivity Cardinal Re said led the pope “to seek dialogue with everyone, never closing the doors to an encounter. For Paul VI, dialogue was an expression of the evangelical spirit that tries to draw close to each person, that tries to understand each person and tries to make itself understood by each person.”

“Ecclesiam Suam” laid out the vision for his papacy, looking at ways the church could and should continue God’s action of setting out to encounter humanity and bring people to the fullness of truth and salvation.

“How vital it is for the world, and how greatly desired by the Catholic Church, that the two should meet together, and get to know and love one another,” he wrote.

But in the turbulent 1960s, it was not that easy. A 1977 biography of the pope by NC News Service—the former name of Catholic News Service—said, “He described himself as an ‘apostle of peace,’ but Pope Paul VI knew scarcely a peaceful day” as head of the church. “Called to the papacy in 1963 to succeed the universally popular Pope John XXIII, Giovanni Battista Montini faced a church and a world experiencing a period of self-criticism and upheaval. His years as pope were most notably marked by the Second Vatican Council—its hopes, reforms and crises.”

Pope Francis greets retired Pope Benedict XVI at the conclusion of the beatification Mass of Blessed Paul VI in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican Oct. 19. Blessed Paul, who served as pope from 1963-1978, is most remembered for his 1968 encyclical, “Humanae Vitae,” which affirmed the church’s teaching against artificial contraception. CNS photo/Paul Haring

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of Pope Paul’s June 21, 1963, election, Pope Francis told pilgrims from Brescia that the late pope “experienced to the full the church’s travail after the Second Vatican Council: the lights, the hopes, the tensions. He loved the church and expended himself for her, holding nothing back.”

A reserved and reflective man who was trained as a church diplomat and spent most of his priestly life in the Vatican, Pope Paul’s papacy was marked by public and often bitter debates over changing sexual morality, the validity of the church’s traditional teaching and the changes in its liturgy called for by Vatican II.

The Mass most Latin-rite Catholics celebrate today often is referred to as the Paul VI Mass. Under his leadership there was a complete revision of liturgical texts, something he said was a source of joy, but it also was a source of some of his deepest anguish. In the last years of his pontificate, he repeatedly repudiated both those who made further, unauthorized changes to the Mass and those who completely rejected the council’s liturgical reforms.

Pope Paul’s connection with the themes raised at the synod on the family Oct. 5-19 include the encyclical for which is he is most known by many people, “Humanae Vitae.” The 1968 encyclical, usually described as a document affirming the church’s prohibition against artificial contraception, places that conclusion in the context of Catholic teaching on the beauty and purpose of marriage, married love and procreation.

In his day—before the globetrotting Pope John Paul II was elected—Pope Paul was known as the “pilgrim pope.” He was the first pope in the modern area to travel abroad, visiting six continents in seven years.

His travels and his meetings with bishops from around the world led him to speak out forcefully against the nuclear arms race, the starvation of millions of people while the rich got richer, a worldwide move toward liberalized abortion and the wars in Vietnam, Israel and Lebanon, not to mention terrorism and guerrilla warfare in many other countries.

Under his leadership, the Catholic Church made huge strides in promoting Christian unity and formalizing its ecumenical dialogues, as well as improving relations with Jews, Muslims and other world religions.

He was born Sept. 26, 1897, in Concesio, a farm town outside the northern Italian city of Brescia. Known as studious and pious from a young age, Giovanni Battista was admitted to the Brescia seminary in 1916, but was allowed to live at home because of his frail health. Six months after his ordination to the priesthood in 1920, he was sent to Rome for graduate studies. In 1922, he was selected to attend the Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy, where the Vatican trains its diplomats. After a year at the academy, Pope Pius XI sent him to the Vatican nunciature in Warsaw, Poland, an assignment cut short because of his health. He returned to the academy and to his studies.

In 1924, he began working in the Vatican Secretariat of State, slowly being given more and more responsibility. At the same time, he served as a chaplain to the Catholic Italian Federation of University Students, which worked to imbue Catholic students with the values needed to counter the fascist student movement.

In December 1937, he was named undersecretary of state for ordinary affairs, a position that made him a close collaborator of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the Vatican secretary of state who became Pope Pius XII in 1939. He worked alongside the pope throughout World War II and was in charge of the information bureau that gathered the names of prisoners of war from all sides and forwarded the names to worried family members.

After 30 years of service in the Secretariat of State, he was named archbishop of Milan in 1954. He spent the next eight years rebuilding and reorganizing Italy’s largest archdiocese. When Pope Pius died in 1958, many people thought Archbishop Montini could be elected pope even though he was not yet a cardinal. Instead, the College of Cardinals chose Cardinal Angelo Roncalli of Venice, who became Pope John XXIII. One of his first acts was to create new cardinals, including Archbishop Montini.

After Pope John died in June 1963, Cardinal Montini was elected pope on the fifth ballot, cast on the second day of the conclave. He was the last pope to be crowned with a tiara; five months later, he solemnly laid the crown on the altar of St. Peter’s Basilica as a sign of his renunciation of “human glory and power.” Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York made arrangements for it to be transferred to the United States, where the crown is preserved at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington.