Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

Strategies in place at schools, parishes, to help kids face down bullies

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published February 20, 2014

ATLANTA—Bullying isn’t just about playground fights anymore. It’s about excluding a student from sitting at a lunchroom table. Spreading rumors about a classmate. Disrespecting someone because she likes different music.

Eighth-graders at St. John the Evangelist School, in Hapeville, know what bullying is all about through a program that stresses respect for all.

As Eden Rorabaugh, 14, said, “It’s definitely not physical. You are getting into their head.”

Fourteen-year-old Kate Calderon said students aren’t physically abused at her school, but since students are followers of Jesus in a Catholic school they need to work harder to include others in activities.

David Wilczynski, 13, said he knows to be careful how he speaks because misinterpreted words can be cruel.

The school is one in the Archdiocese of Atlanta school system that works to prevent bullying as the issue has taken on national prominence. A government website offers tips on bullying prevention. President Barack Obama hosted in 2011 the first White House conference on the issue. The Miami Dolphins suspend a football player that an investigation confirms was bullying another player. Headlines have publicized cases of teens killing themselves as a result of harassment at school and over the Internet.

Catholic leaders are working to make sure schools are safe environments for students. And parish youth programs are also taking up the message.

“You have chosen to be disciples of Jesus Christ, and that means helping other people. It’s not optional,” said Joyce Guris, who organized a recent evening at Transfiguration Church, in Marietta, to talk about bullying to 200 young people and 50 adults. The parish brought in Michael Buchanan, co-author of the “Fat Boy Chronicles” about an obese teen targeted by bullies.

Young people do not need to be bystanders, but can stand up against bullying, Guris said.

“They are not too young to make a difference in the world,” she said.

Trish Gill, a mother of five, attended the workshop. She said, “Kids are the first line of defense” to stop bullying. Parents need to be serious about protecting kids, said Gill, who took her fourth-grader out of public school because of school bullying.

“Her grades were falling because she gave up,” said Gill, who lives in Kennesaw and is a new member of the parish.

‘Everyone is aware something is wrong’

Buchanan speaks about once a month to both public and private schools, in addition to church-affiliated groups.

“People want to do something. They understand it’s a problem, even if they never see it. Everyone is aware something is wrong,” said the former high school math teacher.

His book was based on the experience of a high school student who was picked on for being obese and then changed his life.

Bullying can be curbed by adults and by youngsters, Buchanan said. Too many young people act as bystanders when they outnumber the bullies, he said. There is strength in numbers, and young people should stand up for others getting bullied. But that is a big step for many.

“They don’t feel empowered,” he said.

An idea schools should consider is implementing mentoring programs, so older students work with younger students or athletes team up with non-athletes, he said. The goal is to encourage students to hang out with fellow students they may not otherwise meet in the school community, he said. It can help break down barriers and stereotypes, he said.

At the Hapeville school, eighth-graders teach younger students about respecting each other. Anti-bullying posters hanging on the walls and in the lunchroom reinforce the message.

The school in 2012 enlisted in the national No Place for Hate® campaign, organized by the Anti-Defamation League. The program aims to build communities where all students can thrive. It brings together students, faculty, administration and family members to curb bullying.

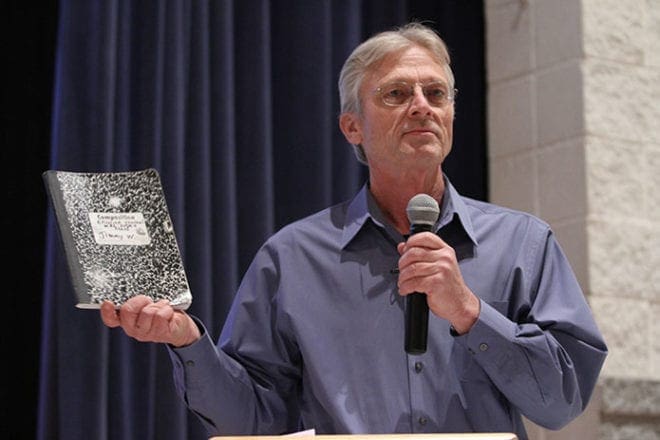

Michael Buchanan holds up the diary kept by the bullied protagonist in the film, “The Fat Boy Chronicles.” Buchanan, co-writer of the film, spoke to middle school religious education students and parents at Transfiguration Church, Marietta, about bullying and obesity. Photo By Michael Alexander

The program requires the school community to showcase classroom diversity and requires students to put a “resolution of respect” into action. “We will seek to understand those who are different,” states the resolution.

Also the school must show its commitment. At least three school-wide activities are to be scheduled. After completing the projects, the school is called a No Place for Hate® school and hangs a banner to commemorate the accomplishment.

For its programs, St. John the Evangelist students organized a performance based on an airplane trip that stopped in all the countries represented in the school. Another was a display of a crayon box, where different colors represented different nationalities.

The program is a good match because it mirrors the school’s mission, according to Megan Davis, the school counselor.

She started the program because respect for the diverse student body is key at the school.

It teaches students to lead classroom instructions on not being a bully and empowers them with leadership skills, she said. The school encourages everybody to be “up-standers” who look out for each other.

“That’s an important skill for your life. It doesn’t just stay within school walls,” said Davis.

‘Respect for each person is essential’

More students at public schools face bullying, according to studies. But private schools are not immune to the problem. One out of five students in private schools reported being bullied. But studies by the National Center for Education Statistics show that bullying is less prevalent in private schools than in public schools.

Bullying reports are handled at the school level, but Diane Starkovich, school superintendent in the Atlanta Archdiocese, said she has heard parents raise concerns about cyber-bullying in grade schools as well as high schools.

Students in archdiocesan schools are held to a code of conduct that they contribute to a positive school environment and avoid “any activity that may be considered discriminatory, intimidating or harassing,” she said. The code also governs activity outside of school hours.

Starkovich said school leaders are committed to a learning environment free of bullying since respect for each person is essential to Catholic tradition.

But it also requires educators and parents to tackle this behavior together, she said. The values of inclusion and respect stressed at school need to be reinforced at home, she said.

The Christian model that is implicit in religious schools gives some leverage to leaders combating bullying.

“We have always had the advantage of relating poor behavioral choices to our faith—our duties and responsibilities as Christians,” Starkovich said.

Student survey helps school plan its efforts

Queen of Angels School examined “hot spots” where students reported bullying took place. In response, teachers have been trained to look for these troublesome situations.

Anti-bullying posters are visible around classrooms at Queen of Angels School, Roswell. They serve as a reminder that there is no place for bullying, and if it is witnessed, it should be reported. Photo By Michael Alexander

The study at the 500-student Roswell school is part of its Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. It teaches staff and students to identify bullying situations, intervene and denounce it, report and follow up. It’s named for the Swedish psychologist Dan Olweus who has spent nearly 40 years studying bullying behavior. It was implemented in 2008.

Guidance counselor Jessica Todd said students from kindergarteners to eighth grade are instructed on the program. Students at this school are exposed to the same pop culture and Internet as their peers, so Queen of Angels began the program to curb bullying behavior and prevent it from occurring, she said.

Todd said a tool not available to public schools is discussions to stop bullying built on faith. All schools say students need to respect each other, but Catholic schools stress the faith-based reason—that everyone is made in the image of God, she said.

“We want to prepare them as citizens of the world and know how to treat each other with respect,” she said

For Todd, it is important students and faculty members know what is considered bullying, and then work to address it.

“The word gets tossed around often in our society. We make sure the kids understand the definition,” she said.

Todd said the school wants to target behavior, so the focus is stopping the action, not labeling students. Students learn bullying is repetitive, intentional and power-based.

“We really want the kids to be standing up for each other” and turn to an adult, she said. Students should not remain silent out of fear of getting involved or being labeled a tattler.

Staff members are trained to identify bullying behavior and intervene on the spot so kids realize it is not accepted behavior, she said.

The Olweus program also uses student surveys to identify problem behaviors and key areas where the behavior takes place in the school. Todd said the survey is helpful because it sets a mark where the school started and where it should focus more of its attention.

She said in the assessment kids identified exclusion, rumors and verbal abuse as troublesome behavior. It found the “hot spots” for the behavior were the playground and lunchroom.

The school has responded by putting more teachers in those areas to supervise students and to actively look for the behavior and intervene, she said.

Another part of the Olweus program is to have students meet regularly in small groups with teachers to discuss bullying concerns.

“That’s where the bullying gets discussed, what it looks like, what to do about it,” she said.

New student surveys showed the instruction is having a good effect, she said.

“All our numbers (of bullying) we looked at decreased,” she said.