Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

Tapestry Of Her Life Has Rich, Loving Colors

By GRETCHEN KEISER, Staff Writer | Published October 14, 2010

To hear out loud that she’s 100 years old sounds “ridiculous” to Mary Brandt Murphy. It makes her laugh.

“I lie in bed and think—what—100! Whoever heard of such a thing,” she said, and when she laughs, you can’t help but join in.

White-haired, with frailties that come with time, the centenarian says that she is still very fortunate.

“I had a pretty good time getting here until lately,” she said of her life’s journey.

“Lately it’s been pretty rough … but here I am.”

Born in Eddystone, Pa., on Oct. 9, 1910, she grew up in North Carolina, where her father ran a textile mill. Her mother was a native of Fayetteville, N.C., and her father came from Virginia, but “a textile man moves around from post to post. Textiles brought them South,” she said.

Her first name is actually Mary Brandt, like her grandmother. Raised Presbyterian, she became a Catholic shortly before her marriage at the age of 22.

“Love brought me into the Catholic Church,” she smilingly says.

Her future husband, Joe, came to see her on Sundays and he was Catholic.

“He had to go to Mass and that took up courting time” so she went with him.

Mary Brandt Murphy has been homebound for nearly six years, so Cathedral of Christ the King pastor Father Frank McNamee celebrated Mass in the Buckhead home of the longtime parishioner two days before her 100th birthday. Photo By Michael Alexader

When she decided she wanted to become a Catholic, she received instructions from a priest. It was 1933, and “it was as hard to get into the Catholic Church as it was to get into the Bastille,” Mary Brandt said.

Although there were few Catholics in the South then, she says she didn’t experience prejudice. Her pastor told her “you are doing the wisest thing” when she told him she was thinking about becoming a Catholic.

“My mother loved my husband very much and she thought he was wonderful. … These were kind, loving people,” she said. “There was no hatred of Catholicism.”

They were married at Belmont Abbey in a solemn high Mass celebrated by three priests with the college choir singing. “I was very impressed.”

Her husband, who was hired to run her father’s textile mill, was a widower with three small children so she became a mother as soon as she wed.

“The word ‘step’ was never used. I was their mother,” she said. “Then I had three sons and we all got along so well. There was never any family friction or anything. It was a great family.”

Although confined to a wheelchair and mostly housebound, she still lives in the Peachtree Hills home she and her late husband came to from North Carolina 57 years ago when he was asked to take a job in Atlanta. Her youngest son, Jack, takes care of her. She is able to listen to books on tape sent by the Library of Congress and she still follows politics and votes.

Married for 61 years, she said, Joe, who died in 1994, “was the most wonderful man. I couldn’t find a better man. He spoiled me rotten, no doubt about that. But I did a little spoiling on my side too. You take, and you give.”

They did “everything together.”

After they raised their family, they traveled a lot, particularly on Audubon Society trips where they could pursue their passion of birding. She said they went to all 50 states, Mexico, England, Kenya, Tanzania, and places as remote as Australia and Papua New Guinea to see birds.

“I have been places you would be horrified,” she said, “but the bird was there and that was what was important.”

“It was so interesting. You just have to see it to believe it,” she said.

“Joe and I had a wonderful life, a wonderful family.”

Her son who cares for her is “an angel without wings,” she said. “Because of my wonderful, marvelous, precious son Jack, I’m making it. He’s just a pure angel in my book.”

She says she loved everything she did, from cooking to keeping her home. In her later years, she created original finely hooked rugs after taking classes in the craft at Chastain. The intricate pieces look as perfect on the underside as they do on the display side, with colors that she dyed into the wool on her stove. Her son says the pieces could take as long as two years to complete. One was created based on a photograph she had of her mother’s home in Fayetteville, that she never saw before it was torn down. Using the photograph, she recreated in the rug the Southern home with its wide front porch, arched trees and cobbled path.

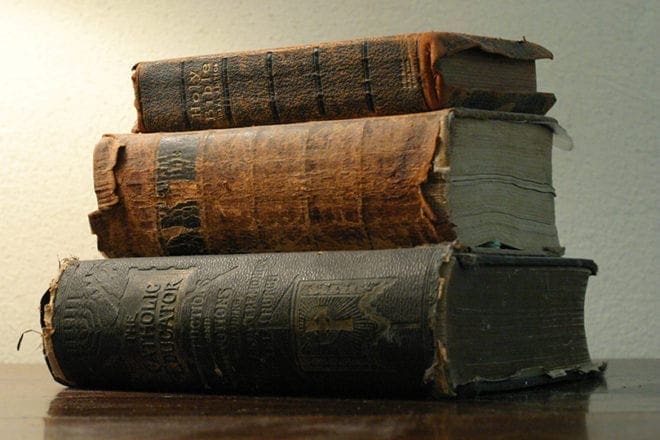

Worn Bibles and a Catholic Educator of instructions and devotions sit on a table in Mary Brandt Murphy’s home. Murphy converted to Catholicism before she married her late husband in 1933. Photo By Michael Alexander

She jokes about her hobby, saying, “I was a stripper and a hooker.”

Asked what she would advise young people about living, she said, “Well, I sound kind of bossy. But be kind. Be interested. And be honest as you can. Sometimes a little white lie slips in. But be kind and honest and interested.”

She says that she cherished in her faith, the sacrament of confession, “getting something off your chest.” She prays prayers of her own every morning and evening.

Her birthday was celebrated warmly, once with a home Mass offered by Father Frank McNamee, pastor of the Cathedral of Christ the King, a few days ahead and again with a party given by her family and closest friends on the actual day, Oct. 9.

A granddaughter arranged for her to receive congratulations from the president of Ireland, Mary McAleese.

Bernadette Flowers, a Cathedral member who regularly bring her Communion, says her time with Mary Brandt is one of the joys of her life.

“She is a very joyful person. She is homebound. She is on oxygen. She isn’t always able to eat. She has got a lot of little nagging things wrong with her. Yet she is a joyful person,” Flowers said.

“You don’t have to be one of her kids or grandkids to feel as if she has embraced you with her love. You can drop in twice a month, and she is just as generous with her love.”

“You learn about the depth of somebody’s faith not always from them necessarily but from the people around them,” she added. “Watching how Jack cares for her. Her other sons come and visit. Her granddaughter comes to visit. Her greatest testimony is her children and her grandchildren, as well.”

“She is very aware of how blessed she is.”