Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael Alexander

Conyers

Fragments Of Color Illuminate Monk-Artist’s Work

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published January 10, 2008

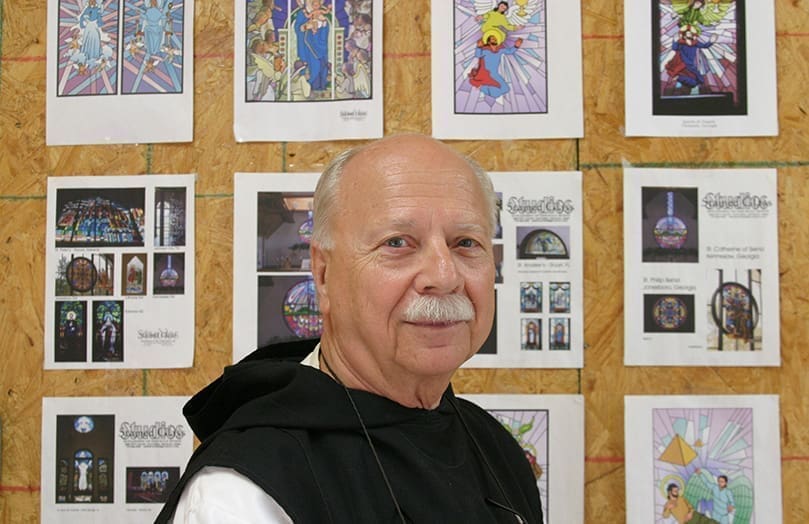

Nearly three years after a fire destroyed Father Methodius Telnack’s Stained Glass Studios, the Trappist monk and self-taught artisan works in a studio newly built for cutting and assembling brilliant stained glass.

The fire and its damage registers now barely a shrug from Father Methodius, as he stands in his work area, which is flooded with light.

“I lost all my archives. I don’t repeat my designs. If I have to repeat designs, it’s time to get out of the business,” he said.

A morning blaze destroyed the original pine monastery in March 2005 while the monks were at Mass. Half a century of stained glass designs in the studio were lost when the 1940s building was left in ashes.

The new studio is taking shape next to the large lawn where the old monastery stood. The studio—there is only one but its name is plural because Father Methodius said it sounds better—is part of the operations at Holy Spirit Monastery where the Trappists hold on to their centuries of tradition.

The monks may pray five times a day, but they need to work in moneymaking ventures to pay the bills. Along with the monastery-made fruitcake and “bonsaimonk.com,” the glass studio is one of the trades that brings revenue to the monastery, which traces its spiritual roots to La Trappe, France. The monastery, home to 45 monks, is some 25 miles east of Atlanta.

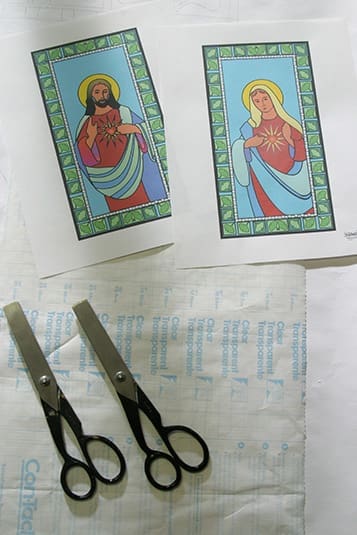

A pair of pattern shears sit on a table with color drawings of Jesus and the Blessed Mother, which are stained glass windows in the works for a chapel in Međugorje. Photo By Michael Alexander

The monastery recently developed a master plan to sustain itself both economically and spiritually in the coming decades. The centerpiece of the plan is increasing its draw with the public. Already, an estimated 60,000 people visit each year.

Father Methodius is a compact 79 years old with a paintbrush mustache and wire-rimmed glasses kept around his neck with a string. He learned about stained glass by studying books from the Atlanta Public Library and relied on help from other artisans.

He studied architecture briefly at the Catholic University of America before entering the monastery. Father Methodius’ first on-the-job training was pitching in to design the monastery and the abbey church when the hired architect died.

“It was kind of one job led to another,” he said.

One prominent piece of his handiwork is the bell tower where three bells—St. Michael, St. Raphael and St. Gabriel—ring out five times a day.

As he started out, he heeded a piece of advice: Keep a ready supply of Band-Aids on hand.

“You can’t work with glass without getting cut,” he said.

Computers have changed the work of making the windows. Designs are done on the computer first because it is easier to manipulate draft layouts. The pattern is a guide as Father Methodius uses special scissors to cut shards of glass, as if creating a vivid jigsaw puzzle. He uses raw materials from Blenko Glass Co., in West Virginia. He’s had a relationship with the company nearly since he started.

As for prices, Father Methodius said the cost of everything has gotten more expensive. He is still putting the final touches on the 2008 price list.

Father Methodius has been at the craft for some 50 years and talks about handing it over at some point in the future. And he has come to appreciate a suggestion he heard when he feared the creative well was dry.

“There’s no such thing as a bad design—just keep perfecting it,” he said.

It is his handiwork at St. Philip Benizi Church in Jonesboro where abstract flowers bloom from a cross. His art is also at St. George Church in Newnan and St. Thomas More Church in Decatur, where he created the window in the eucharistic-themed chapel.

On the table now are two windows for a new chapel in Medjugorje, the Marian shrine in the former Yugoslavia. The window patterns show images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

A new stained glass studio was completed in the fall of 2007 to replace the one destroyed by a March 2005 fire. Photo By Michael Alexander

Non-Catholic churches also have his work. The sacristy of St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church in Decatur has a sunflower created by Father Methodius.

Among his earliest works, in fact the first, are the tall windows in the abbey church where flashes of blue, pink, white dance on the wall. The windows are in a style that dates back hundreds of years called Cistercian “grisaille” glass.

At work in this field for long years, Father Methodius has seen trends change. He said parishes want realistic figures featured in windows. People mistake this realism for the traditional heritage of the stained windows in the Catholic Church.

“I believe there is a more conservative reaction going back to the modern, instead of the traditional,” he said, looking over a wall of design prints.

This stained glass window of the Holy Family is the work of Cistercian Father Methodius Telnack, a monk who resides at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, Ga. The window is in the narthex of Christ Our Hope Church, Lithonia. Photo By Michael Alexander

For instance, one of his colorful windows installed in a church in Alabama interprets a triple exposure photo of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica.

Today, he believes people wouldn’t approve such a design, although the imaginative design more resembles the famous windows of Chartres Cathedral in France than the figures on his drawing board now.

But he always bows to the wishes of parish leaders commissioning him, not his own. At meetings, he welcomes criticism from parishioners because he feels a window should reflect the people who worship there, not exist as a generic piece of art. He said pastors often leave design meetings out of concern the parishioners are too critical and hurt his feelings. He wants the input, however.

Every church needs its own glass is how Father Methodius puts it.

Officially known as the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, the religious order takes its nickname from the city of La Trappe, France, where a reform of the 900-year-old Cistercian order began in 1664. They are members of the Benedictine family, taking the sixth-century rule of St. Benedict as a guide for monastery life.

The rule requires the monastery be self-sustaining, or “by the work of their hands,” as St. Benedict wrote in the chapter about daily work.

Father Methodius, a son of a Ford worker and a mother who spoke seven languages, visited the monastery during leave from Catholic University of America. It was there he got his most formal education in the arts, a year studying architecture.

He marked 50 years as a priest in 2007 and started his life as a monk in the monastery that once stood in the empty grass-covered lawn. It began with a 10-day visit.

“I just got real homesick and I didn’t want to leave. I came back in August and I didn’t leave,” he said.

The Monastery of Our Lady of the Holy Spirit is located at 2625 Highway 212, SW, Conyers. The main number is (770) 483-8705.