Is there room at the inn for the incarcerated?

By BISHOP BERNARD E. SHLESINGER III | Published December 12, 2025 | En Español

During Advent this year, the church will celebrate a Jubilee Year for Prisoners worldwide on Dec. 14. This celebration takes place almost one year after Pope Francis opened a Holy Door at Rome’s Rebibbia Prison, signaling the church’s radical commitment to including those on the margins of society in its most sacred celebrations.

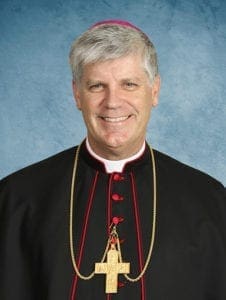

Bishop Bernard E. Shlesinger III

I will be participating in this worldwide celebration by offering Mass at the Federal Correctional Institute and joining countless others in a specific focus on the millions worldwide who are incarcerated, detained or awaiting execution—individuals who have not lost their dignity as human beings despite their state of imprisonment.

Besides showing a commitment to our brothers and sisters when they are in prison, I am challenged to think of what may happen to them when they are released. How radical is my commitment to them on their journey of restoration to society?

Being released from prison is not synonymous with a restored freedom, especially if individuals who have once been incarcerated are not welcomed back into society. They may feel like there is no hope for them in the future and that their human dignity is no longer respected. Even prior to release, the physical location of prisons, as well as dehumanizing treatment of people who are incarcerated, severs links between people on the inside and their families and communities on the outside. Isolation is not the answer to human development.

As Catholics, we believe that the human person is social, that our relationships are constitutive of our very existence. When these relational and social bonds are weakened and destroyed through both systemic pressure and individual choices, we see increased criminal activity. Restoration and reconciliation involve supporting and rebuilding family and community ties which are central to any efforts to prevent crime and lower recidivism (repeat offender) rates. Sadly, the recidivism rate of people who have been incarceratedremains extremely high.

There are proven strategies for reducing recidivism rates, all of which support in some way the rebuilding of relationships and community. Education and job training, housing assistance, healthcare, social support and community-based support programs are all proven to help people in the reentry process.

We must resist narratives that tell us people who have committed crimes in the past will do so again because it’s in their nature. Recidivism rates continue to be high because many of those incarcerated are released without support, often returning to a society that labels them as a “criminal” or “felon” and restricts where and how they can live, work or study.

During this Jubilee Year for Prisoners, we may think of a Holy Door at the Rebibbia Prison in Rome, but I think of the door to our hearts, which should be open wide not only to Christ but to those who have lived in an enclosed environment.

Advent is a time for making room for God. When we think of Mary’s response to the angel Gabriel, she did not say “what must I do.” She asked, “How can this happen?” She opened her future to welcoming God, leaving room for God to be incarnate.

As we look forward to the advent of justice and liberation at Christmas, we must ask ourselves: do we make room for the poor? Do we promote a society that makes room for the unborn? Is there room at the inn of our minds, hearts, communities and our parishes for the incarcerated?