‘Time and the bell have buried the day:’ Pro football and gratitude for the liturgical year

By DR. DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published December 8, 2024

I love pro football. I always have. As a Generation-X child of the 1970s, how could I not adore the game? It was engrained in our consciousness as part of NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle’s brilliant campaign to market the sport to the young and the hip, and it took hold.

If you talk to anyone “of a certain age” around the secular holiday season, chances are good that they will remember the Sears-Roebuck Christmas Wishbook, which appeared in mailboxes all over the country usually in mid-November.

Among the fixtures of the Wishbook were the pages devoted to NFL merchandise. If it could be worn, it could be festooned with team logos. From sweatshirts to jackets to knit caps to socks and even bedroom linens and furnishings, the NFL made sure that any boy or girl could outfit their entire life in NFL regalia.

I grew up a hardcore Atlanta Falcons fan, and I still am. It’s penance you know. I had all the Falcons gear you could get from Sears, even a helmet. My friends and I used to hate that the full-page spreads in the catalogs always featured the perennial winners—Cowboys, Steelers, Raiders, Dolphins. The Falcons never headlined the department store catalogs in those days, though the NFL pushed them front and center in their own merchandise brochures, as they were trying to grow the pro brand in the land of college football.

With Thanksgiving here, it’s almost as essential as turkey and dressing that we have a feast of pro football. The NFL has ensured that we will get three games on Thanksgiving—including the long-time fixtures of the Detroit Lions and Dallas Cowboys home games—as well as a special “Black Friday” game the next day. Then of course we get the regional weekend games as well. My wife complains about all the football. I complain about the pots, pans and dishes. We’re even.

The argument can be made—in fact I’ve written about it before—that NFL football on Thanksgiving Day is older than the national holiday itself. Pro football has been played on Thanksgiving since 1920, two decades before Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the federal holiday in 1941. The Detroit Lions have played on Thanksgiving since 1945; the Dallas Cowboys since 1966. Midway between those years, in 1956, all the states finally agreed to recognize the national holiday.

Concerning time

The most fascinating aspect of pro football to me is its concern with time, one might even say its mastery of time. Not long ago, people such as the great writer Roger Angell could wax poetic about the eternal aspects of baseball. A baseball game once had no clock at all; it could conceivably go on forever. Now of course, we have imposed the pitch clock, and the extra innings rules, that have revoked baseball’s sense of the timeless.

Yet football still fascinates the viewer by creating the illusion that we can manipulate time. We can call time-outs. We can get out of bounds to stop the clock. We can spike the ball at the line of scrimmage and garner just one more chance. Contemporary baseball now invokes the inevitable. Football more than ever inspires the hopeful illusion that we can control the passage of time. Even at the very last second, there is hope for a conversion.

I am dismayed, as I am every year at this time, at our rush to celebrate “the holidays.” I have heard people say that Thanksgiving is so late this year; it gives us less than a month until Christmas! On my street, there are homes that were decorated for Christmas the day after Halloween. In the stores that all of us shop, Christmas decorations appeared for purchase even before Halloween.

Have we forgotten the wisdom of Ecclesiastes, that “to everything there is a season and a time to every purpose under heaven?” Have we forgotten St. Paul’s edict that at last, “Now is an acceptable time for salvation?”

Catholics should remember that we have a liturgical year, separate from the secular calendar. Advent begins at an appointed time and concludes with the end in mind—a celebration of a miracle and an appreciation of that miracle’s growth across Epiphany and Candlemas.

In the early days of the modern NFL, Commissioner Bert Bell used to figure out the league’s schedule at his kitchen table. He literally plotted all the games for the upcoming season on index cards. When he was finished with his work, it was fixed—much as the liturgical calendar is fixed and figured years in advance.

Each year the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops publishes a roughly 50-page bilingual document that outlines nearly all liturgical matters for the coming year. I know that 2025 begins on Dec. 1, the First Sunday of Advent. I know that the readings for Sundays will come from Cycle C and the weekday texts from Cycle 1. I know the dates for every Holy Day of Obligation and Optional Memorial and Solemnity. Should I need reminding, in a few weeks I can walk in nearly any Catholic parish and get a free calendar that outlines the entire year ahead.

One of the great comforts of the Catholic liturgical year is its certainty and its relative lack of change. In its ordering of time, it has become almost timeless.

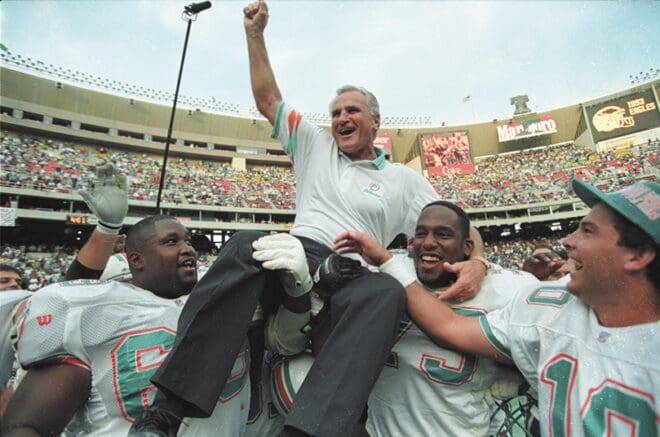

Don Shula is carried off the field after defeating the Philadelphia Eagles in this 1993 file photo. The legendary Miami Dolphins coach died in 2020. CNS photo/Gary Hershorn, Reuters

Sports in America—particularly football—were once similar in that they followed reasonable set patterns. Baseball was like Ordinary Time, covering nearly nine months from Spring Training to the World Series, which nearly always ended in early October as nature intended. The Masters, The Kentucky Derby and The Indianapolis 500 were like special Saints’ days. The Stanley Cup, NBA Finals and Super Bowl were like solemn memorials, but with an understanding that less is more.

Go in just about any church in America—Catholic or Protestant—and stand in the pulpit looking out over the pews. I can almost guarantee that your eye will be drawn to a large clock, usually mounted on a choir loft or balcony, which never lets the priest or minister forget that he is bound to his congregation by time.

Perhaps sports pundits need a similar memento mori. So much of sport now seems unnecessarily bombastic and exaggerated, even at the amateur level. We spend more time forecasting and analyzing than we do watching the actual event, and we are now disturbingly occupied with win probabilities and betting odds. It’s a commentary upon our societal priorities that we spend more time preparing for a game than we ever do for school, an appointment or church.

The great Anglo-Catholic poet T.S. Eliot wrote a masterful meditation upon time in his cyclical “The Four Quartets.” The poems affirm the transient nature of the present, the mystery of the future and the permanence and influence of the past. Eliot frames the four long poems in the cycle in specific places—an English garden, the New England coast, an ancestral home and a lonely church yard. He demonstrates that the relationship between time and place can be both mundane and mythical, as plain as a simple homily or as thrilling as a last-second Hail Mary pass.

Two of the NFL’s greatest coaches—Vince Lombardi and Don Shula—were devout Catholics. Lombardi is an American icon, synonymous with both competition and sportsmanship. Shula coached the 1972 Miami Dolphins, the only pro football team to ever have a perfect season. Both men are vaunted as models of success. Yet each was also fascinated and humbled by his faith. Lombardi owned a bishop’s vestments and miter. Shula almost entered the priesthood. And each man thought a lot about time.

Lombardi’s players lived and worked according to the principle of “Lombardi Time,” which meant that if you weren’t 15 minutes early, you were late. It’s not as eloquent as Eliot, but Shula’s philosophy that “Success is not forever and failure isn’t fatal” is a wise and practical insight.

American Thanksgiving has always been a blend of providence and pleasure. If William Blake is right, that “Heaven is a playground,” I’ll let my Catholic imagination find mystery and meaning in a time that embodies the principles of each. Happy Thanksgiving.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of OCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.