70 years later ‘On the Waterfront’ testifies to the importance of truth

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published February 28, 2024

It is a lesson I have always told my students, and one that I repeatedly impart to my sons: don’t spend more time doing the wrong thing than it would take to do the right thing in the first place.

In short: tell the truth.

Contemporary news, all over the world, is filled now with multiple examples of people who seem never to have learned that simple lesson.

The great American film “On the Waterfront” celebrates its 70th anniversary this year. The context in which it was made, and the rich subtexts of the film, are especially relevant to Catholics during Lent, a time in which we make sacrifices and attempt to deepen our examination of conscience.

At the same time, the film remains a masterwork of the studio era in terms of its direction, its cinematography, and its performances. It is an iconic movie that continues to challenge and provoke audiences, particularly in how it addresses themes of honor, honesty and redemption. It is a great Lenten film; in my mind, it actually captures on film the simultaneous bleakness and promise of the penitential season.

Director Elia Kazan’s own life is a remarkable story. At the age of 4, he immigrated to the United States from the former Constantinople. A member of the Greek Orthodox Church, he received catechesis in Catholic school. Known for his social idealism, he valued fidelity to both God and country, and he was always deeply grateful for the opportunities he had in America.

Kazan was also a great artist, a co-founder with Lee Strasberg of the famous Actor’s Studio in New York City, and a masterful teacher of the Stanislavski “Method” approach to acting. Kazan’s filmography contains some of the greatest films in American cinema including “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” “Panic in the Streets,” “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “East of Eden.”

In 1952, during the House Unamerican Activities Committee Hearings on Communism in American art and culture, Kazan famously named names of suspected communists. He defended his decision to inform based on his deep patriotism, but much like Terry Malloy in “On the Waterfront,” he was widely vilified for his testimony. When he received a lifetime achievement Oscar in 1999, much of the audience refused to acknowledge him, yet there were also those who appreciated his commitment to the ideal of a greater common good. Sadly, Kazan’s naming of names cost his friendship with Arthur Miller, for whom he had directed the Broadway premiere of “Death of a Salesman.” Miller later referred to Kazan as a “stool pigeon,” a hurtful reference to “On the Waterfront.”

The film was without a doubt Kazan’s answer to his critics, and his own steadfast defense of his ideal of the American Way. The code of “Deaf and Dumb” that defines the Hoboken waterfront in the film is a weak, “hear no evil; speak no evil” ethos that simply doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

Terry Malloy, played by Marlon Brando in one of his most famous roles, is a former prize fighter who was sold out by his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger). Terry, who once “coulda had class, coulda been a contender, coulda been somebody,” is now simply an errand boy for the crime boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), who controls almost every aspect of the Hoboken shipping business. Terry is charged with assisting in setting up Joey Doyle, a potential witness for the Crime Commission who has information that could cause serious trouble for Friendly. Terry believes that Joey will simply be roughed up; when he is in fact murdered—pushed off a rooftop—he feels deeply betrayed and wants to report the crime.

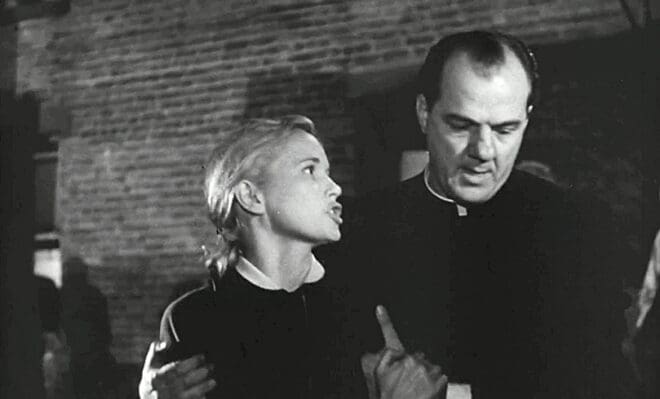

Not long after Joey’s murder, Terry falls in love with his sister Edie, played by Eva Marie Saint in her feature film debut. Terry confesses what he knows to Edie, who is furious, as well as to a parish priest, Father Barry (Karl Malden). They urge him to tell the truth to the Crime Commission, but Terry refuses because of the “Deaf and Dumb” code. When Friendly kills a dock worker, Kayo Dugan, as a show of his power, Terry is urged even further by Father Barry to testify. When Terry’s own brother Charlie threatens to kill him if he talks, Terry makes up his mind. Friendly has Charlie killed when he fails to murder Terry, and Terry then goes to the Crime Commission. Further justice is meted out in the film’s famous final scene.

Eva Marie Saint as Edie Doyle and Karl Malden as Father Pete Barry in a scene from the 1954 film “On the Waterfront,” which focused on union violence and corruption among longshoremen in Hoboken, New Jersey. OSV News photo/Public Domain

In the film, the scrutiny—or conscience—is provided by Edie, who loves Terry deeply, and especially by Father Barry, who urges Terry to expose the hypocrisy and evil rampant on the docks and in the larger environs.

Character modeled after Jesuit priest

Father Barry is based upon a real waterfront parish priest, Father John Corridan, a Jesuit who fought corruption in labor unions. Screenwriter Budd Schulberg described him as a “Rangy, ruddy, fast-talking, chain-smoking, tough-minded, sometimes profane” Roman Catholic priest who wanted to expose the corruption on the New York/New Jersey docks.

Father Barry “works on” Terry much like the dockland hoodlums threaten any potential stool pigeons. Terry complains to the priest, “If I squeal my life won’t be worth a nickel.” Father Barry doesn’t skip a beat: “And if you don’t squeal—what will your soul be worth?”

There are many fine scenes in the film with Father Barry, whose pursuit of justice saves the lives of men who don’t necessarily deserve redemption. Yet the greatest moment in the film for Father Barry, and the initial turning point for Terry to understand the martyrdom of those who are unjustly killed in the name of silence and subterfuge, is the outstanding scene in which Dugan is murdered, crushed by a load of freight dropped upon him from a crane.

Malden is especially brilliant in this scene and is depicted—like Dugan—as a Christ figure. After Dugan is killed, Father Barry says angrily that “Some people think the Crucifixion only took place at Calvary.” He goes on to explain that in all our suffering, just or unjust, we all partake in a part of Christ’s Passion. Father Barry condemns complacency and apathy. After he administers last rites to Dugan, he is heckled—“Go back to your Church.” He is pelted with garbage. His answer is “This is my church.” Further, he tells the dockworkers that when they show up every morning looking for work, Christ is with them. He assures them that Christ knows their needs. Wherever injustice is done, that is where Christ will be. The entire scene is shot with visual references to the cross.

Frank Sinatra desperately wanted the part of Terry Malloy, but thankfully it went to Marlon Brando, the brilliant Method Actor, who—typical of Brando—was uncertain if he even wanted the role. Brando used cue cards throughout the filming so that his dialogue would seem more spontaneous and authentic. Authenticity is further accomplished by the brilliant on-location cinematography, much of it shot outdoors in near zero temperatures. The film had a profound influence upon the filmmakers of the French New Wave a few years later; Francois Truffaut and Jean Luc Godard pay homage to the movie in their great first features “The 400 Blows” and “Breathless.” The film was also among the first 25 movies selected for inclusion in the Library of Congress National Film Registry.

“On the Waterfront” won eight Academy Awards—Best Picture, Best Actor for Brando, Best Supporting Actress for Saint, Best Director for Kazan, Best Story and Screenplay for Schulberg, Best Editing, Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction. The wonderful supporting cast of Karl Malden, Lee J. Cobb and Rod Steiger were all nominated for awards, though none won. Leonard Bernstein was nominated for Best Music, but did not win, and many people still deride his overbearing score.

We are often encouraged in Lent to think not so much about “giving up” things and focus more upon adding aids to greater spiritual development. For me, literature and film are wonderful ways to develop faith, for faith cannot fully thrive without an active imagination. Like “On the Waterfront,” many great Hollywood films of the 1950s and 1960s are approaching milestone anniversaries, and revisiting these classic movies inspires the intellect, the emotions, and the spirit.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.