Thomas Merton’s ‘Original Child Bomb’ and the Oppenheimer film

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published August 21, 2023

Like many people, I went all in for the so-called “Barbenheimer” movie phenomenon of the past few weeks. I saw both films, and as both a film professor and a moviegoer, I do confess that I was thrilled to see the Hollywood blockbuster return to relevance this summer. I thought both movies were fantastic, and while I won’t succumb to acknowledge which I thought was better, I will report that I saw “Oppenheimer” first on the opening weekend and “Barbie” second on the subsequent weekend.

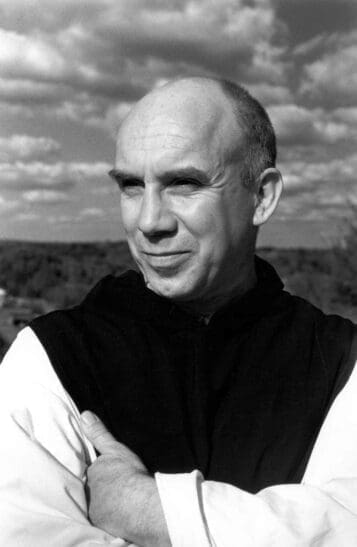

Trappist Father Thomas Merton, one of the most influential Catholic authors of the 20th century, is pictured in an undated photo. CNS photo/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

The subject of this column, however, is Christopher Nolan’s film “Oppenheimer”—not so much his movie, which is excellent, but what it made me think of.

There is a brilliant short montage sequence early in the film that positions the young Oppenheimer during the High Modernist period. We look with him in an intense consideration of a Picasso painting. We see him reading T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland.” We hear him place Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” on a record player. In about a minute, we are in his landscape and mindscape, and when Albert Einstein inevitably appears, we are fully immersed in the period.

So, too, was Thomas Merton, who at the same time Oppenheimer was being named director of the Manhattan Project made plans himself for another mysterious vocation as a Trappist monk.

As the Oppenheimer film moves toward its inevitable climax with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I could not stop thinking about “Original Child Bomb,” the “anti-poem” that Merton wrote about the bomb in 1961, nor could I stop thinking about the wonderful film adaptation of the poem produced by Mary Becker and directed by Carey McKenzie in 2004. I do not know if director Nolan was aware of either Merton’s poem or the more recent film, but I do know that I thought of both and wanted to share each with you.

A poem to contemplate and discuss

Merton’s poem is not poetry in the sense that most people think of. It is divided into 41 numbered sections and contains about 2,500 words. Its tone is cold and ironic. It reads like the linguistic equivalent of bitter medicine.

Merton wrote the poem at the height of the Cold War, when he was writing passionately, prolifically and often privately about the threat posed by nuclear weapons. As the poem states in its final line, “At the time of writing, after a season of brisk speculation, men seem to be fatigued by the whole question.” He published the poem in the little magazine Pax, and in 1962 New Directions Press published the poem in book form. The poem is easily found today online, in several websites that are often Catholic, and almost always from a non-violent perspective.

Writing about the poem is difficult. It is a work that almost must be read and contemplated on a subjective level. Its effect will vary according to the reader. I do know from years of teaching the poem, in conjunction with the film adaptation, that the poem is best appreciated when discussed with others.

The film is best seen after reading Merton’s poem. Yet to consider the film only as an adaptation of, or homage to, Merton’s poem is unfair. The poetic image is different from the cinematic image, and while the message of both poem and film is the same, the film merits consideration of its own. As with Merton’s poem, the film can be seen online; in 2020 Mary Becker re-released the film and posted it on YouTube.

The film is comprised primarily of carefully edited archival footage, much of it now declassified and exhibited here for the first time. The film opens with shots from 1940s Hiroshima. Children are playing, people are walking the streets—smiling, shopping, working, simply going about the routine of daily life. There is a startling low angle shot of a little girl, a cut to a plane in the sky, and the juxtaposition of innocence and power is shocking. These are real people, the audience thinks, and that is a real plane, yet how the two collide with one another seems horrifyingly unreal. When the bomb makes impact, then, instead of seeing a literal image of its destruction, we see a starkly terrifying animation sequence that imagines what still is almost impossible to imagine.

It is useful to compare this sequence to how Nolan connects Oppenheimer’s vision of the Los Alamos audience to what he imagines must have happened in Hiroshima. Merton’s description is startling: “the people became nothing.”

Throughout, the film utilizes a rhythm of contrasts, what film theorist Sergei Eisenstein called oppositions. Beyond the effective and frequent juxtaposition of live action and animation, black and white footage alternates with color; newsreel footage of the bombings and Cold War nuclear tests is contrasted with reaction from contemporary students; and throughout we see and hear from American children and Japanese children, the young and the old, those scarred emotionally and those maimed physically.

Perhaps the greatest effect of this constant shifting of perspectives is that it underscores the universality and enduring implications of those horrible days in August 1945. The film makes clear that rather than being a past threat, the possibility of nuclear holocaust is even more real today. The film only conveys the statistics that really matter; beyond the obligatory death tolls of the atomic bombings and the horrifying numbers of people who later died from radiation effects, the film makes clear the fact that there still exist thousands of nuclear warheads, with more likely in production.

I’ll not summarize here all the sequences in the film; to do so would detract from your own first encounter with it. I do want to address, however, a few techniques that emphasize the resonance of past events upon the present. In one effective sequence, for example, we meet a young Japanese boy who explains that when he first learned about the atomic bombings in the sixth grade, “it hurt [his] heart a little.”

The remarkable footage of the Japanese boy contrasts with that of American high school students who express a full range of opinions about their feelings about the bombings, and their sentiments range from compassion to rage, from shock to a disturbing sense of inevitability, even perhaps ambivalence. In his poem, Merton certainly wanted to address not only the horror of the children who died, but also the tragedy of all the children who might die in similar attacks.

I saw “Oppenheimer,” which has a run time of three hours, in a row of seats occupied entirely by teenage boys. Not even one left his seat during the entire film. They watched, awestruck. Some of the best moments in “Oppenheimer” inspire this kind of stunned silence. But silence, as Merton knew so well, can be a remarkable catalyst for action.

As a teaching film, “Original Child Bomb” is meant to appeal to those boys with whom I watched “Oppenheimer.” Its ambient soundtrack is immediately recognizable to a young audience who know and admire much of the music and musicians who contributed to the film. Indeed, much of the film’s pacing and editing is very similar to contemporary music videos.

Finally, that the film is fully aware of itself as a film is demonstrated by the frequent use of onscreen text and literal stops, reversals, and fast forwards. This approach achieves a jerky, edgy effect that is relevant to today’s new digital media, but it also echoes the tone and rhythm of the Merton poem, several passages of which are coldly recited in the film.

At one point in “Original Child Bomb,” we hear from a Japanese woman who recounts the story of her young daughter who survived the bombing only to die a few months later of a seizure caused by radiation effects. The mother remembers her grief and says “but I suppose you cannot undo the past.” Merton certainly hoped to redeem the past with his poem, and this film adaptation has the same aim.

As “Oppenheimer” reminds us, a terrible beauty was indeed born in August 1945, and though the human capacity for hope, compassion and empathy was not destroyed by the bombs, it certainly needs constant nurturing from generation to generation. If Christopher Nolan’s film made an impression on you, Merton’s poem and the film inspired by it will further enhance your understanding and appreciation. At the conclusion of each, you may indeed be inspired to pray, as one of my students once did: “May God have mercy on us all.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.