Youth baseball from a Catholic parent’s perspective

By DAVID A. KNG, Ph.D. | Published July 7, 2023

My family and I returned last week from a wonderful trip to Cooperstown, New York, the site of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the mythical home of our national pastime.

I have wanted to visit the Hall of Fame for my entire life, and it is no exaggeration to say that I trembled with excited anticipation as we approached the entrance.

The experience of visiting Cooperstown is overwhelming for a baseball fan. Card shops line the town’s main street. Memorabilia stores are everywhere. A wax museum of baseball heroes is almost as fine as the Hall itself.

Within the Hall, it only gets better. One of the first things I saw was the bat that Ted Williams broke in anger after having been struck out by the great Satchel Paige, the Black pitcher whose major league career was all too short, and for whom Williams argued for inclusion in the Hall of Fame.

I saw the uniforms and personal belongings of Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Lou Gehrig and Hank Aaron. I saw Stan Musial’s locker. I saw the gloves of Brooks Robinson, Sandy Koufax and Willie Mays. I beheld the glories of the 1969 New York Mets and the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers. I saw artifacts from nearly every great baseball movie ever made. I saw the typewriters and glasses and notebooks of writers and announcers as beloved as Roger Angell, Harry Caray and Vin Scully. I saw, and I couldn’t believe it, and I almost wanted to ask, like Shoeless Joe in Field of Dreams, if I was in heaven.

And then I saw a film. My younger son insisted we see it. We were in Cooperstown because his baseball team was playing in a tournament at Cooperstown Dreams Park. I didn’t really want to watch a museum film, but he persisted.

I am glad I listened to him, because the 16-minute film we watched, “Generations of the Game,” is quite possibly the best baseball movie I have ever seen. People were deeply touched by all we associate with baseball: its heritage, its myth, its deep place in our collective American memory and imagination.

Of all that I saw in the Hall of Fame, nothing quite surpasses an image that I will never forget from watching this stellar short film. In a brief segment explaining the utter devotion to the game in the Dominican Republic, pitcher Pedro Martinez describes how important baseball is to Dominican children. Footage of children playing ball in crowded streets and dirt lots reveals their obvious love for the sport.

The children are playing, however, not with bats and balls and gloves, but with sticks and anything at all that approximates a baseball. Their “mitts” are cereal boxes, empty boxes of Cheerios and corn flakes, with ends opened and the boxes folded and flattened so that a child can catch, or capture, whatever comes his way, be it a ball of socks or a rock. I was deeply moved.

Future of the greatest game

My son had spent nearly a week of pageantry and games and boyhood frivolity at Cooperstown. But as I watched those Dominican children play with cereal boxes and sticks, I wondered how much he might have learned about inclusion, sportsmanship and fair play.

What if Jesus coached a baseball team? A child’s baseball team. It’s too easy to think who he might choose if we are talking about big league players past and present. No, I’m thinking about children. Who would he pick? I’m pretty sure the Dominican children would be at the top of the list.

There has been a lot of discussion in both the secular and Catholic press lately about children’s sports.

Just over a year ago, John W. Miller wrote an eloquent and informed article in the 19 May 2022 issue of America Magazine on the state of Little League Baseball and youth sport in general. The article is titled “How America Sold Out Little League Baseball.” Miller wrote as an authority, as someone who had coached in “Travel Ball” and who was also a fan of the game.

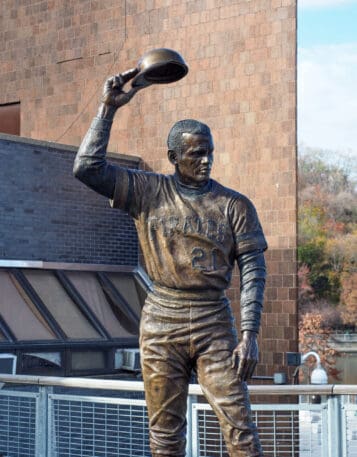

This statue of Roberto Clemente is situated in Roberto Clemente State Park, Bronx, New York. He learned to play baseball in his native Puerto Rico and died while on board a flight taking emergency supplies to earthquake-stricken Nicaragua in 1972. Photo by Roy Smith via Wikimedia Commons

I’ve thought about Miller’s article a lot, for as my regular readers know, baseball has been a big part of my boys’ childhoods. As much fun as I had in Cooperstown, I am left troubled about the future of our country’s greatest game.

Babe Ruth learned the game in a Catholic reform school in Baltimore. Roberto Clemente learned it in Puerto Rico, when he had time off from work in the sugar cane fields, and he devoted his short life to making baseball a means to minister to others. Clemente is now being considered for sainthood. Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays and Hank Aaron and more than 30 other players in the Hall of Fame played with dignity and grace for years in the segregated “Negro Leagues” before being accepted by Major League Baseball and paving the way for hundreds of others.

Yet for all its good works, baseball has always been connected to ethical dilemmas, whether the Black Sox Scandal of 1919; the argument over the Reserve Clause, labor disputes, and free agency; Pete Rose; and the steroid crisis of the 1990s.

Now youth baseball faces new problems. Little League, founded by Carl Stotz in 1938, remains a cherished national institution; my own children played for years in Little League, and for the most part they had great experiences, as the League does try to live up to its motto of “Character, Courage, Loyalty.”

Yet Little League is under threat now by the sprawling numbers of “Travel Teams” that all over the country are vying for talent, time and profit. The money and anxiety associated with this brand of youth baseball astonish me.

Boys (and only occasionally a girl) my son has played with and against use bats and gloves that cost hundreds of dollars. They take private lessons that can cost as much as $100 an hour. They play in tournaments that often occupy an entire weekend and occasionally require trips far away from the neighborhood park. They practice, even on school nights, into the dark. A family who commits to “Travel Ball” may expect to devote five days a week to the team, and membership on these teams, which requires assessment, can cost thousands of dollars. And often, the child can spend an entire game on the bench. That time isn’t spent in peace and quiet. It’s wracked with stress and worry about not being good enough. Yet 12-year-old boys (and often their parents) can’t seem to get enough of it. To be on a travel team equates with social status in middle school.

To me, baseball or any other sport should not be about status. It should be about fun. It should be about learning to win with poise and lose with honor. It should be about playing with all sorts of people from all walks of life, not just families who make enough money to buy top-shelf equipment at the sporting goods store.

Some people argue that the for-profit leagues are a great way to vie for academic scholarships, yet the fact is that only 2% of teenage athletes will get a college scholarship. Still, youth sports subtly peddle the idea that excellence in child’s play will equate with a free ticket to college.

The problems inherent in for-profit kids’ sports are making an impact in both the culture and the big leagues. Major League Baseball has founded a program called “RBI”—Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities—because Black participation in baseball continues to decrease.

In society, at a time when adolescent mental health is in crisis, the last thing children need is for the games they play to cause anxiety and wounded self-esteem.

Youth sports conjure images of screaming parents, beleaguered umpires and referees, and obscenity-laden tirades on benches, but in 12 years, those stereotypes haven’t been my experience at all.

Instead, I have witnessed a passive acquiescence to behaviors that are subtle, but just as alarming: favoritism, autocracy, inequities about money, misbehavior that goes unpunished.

While I honor and respect everyone who gives volunteer time to nurture children, I can’t help but be concerned about those who are in a cherished game for their own selfish benefit.

I think of one of my childhood role models, Bill Mackey, a life-long acquaintance who epitomizes for me the Catholic coach and parent. Coach Mackey set as a goal to win half the games, and there were no “all-stars.” He honored effort and equity. I wish my children could have had him as a coach.

But it’s summer, and the days are long, and when the humidity breaks, the backyard ball games at the King house are in full swing among the lightning bugs, and for a moment it can feel like heaven. That’s how baseball should be.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.