What News Horatio? Poems by Gary Bouchard

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published November 2, 2022

If you live in, or travel through, the East Cobb neighborhood of Metro Atlanta, you probably know about Woody the parrot. Woody went missing from his home last Thanksgiving, and he became the subject of much fascination. His owner offered a generous reward for his return, and there were occasional sightings of the bird. Just a few days ago, I noticed that at least one of the signs about him remains hopefully fastened to a telephone pole.

I like to think of Woody, missing though he may be, as akin to Thomas Hardy’s “Darkling Thrush,” a bird overheard 120 years ago in England, who trilled a song that to the poet seemed “Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew and I was unaware.”

I wish Woody well, wherever he may be, and hope that he might return. After all, a parrot in California vanished for four years and returned home safely, unchanged except for the fact that he had learned to speak Spanish.

In a chaotic and troubled world, we need to find hope in creatures like Woody. We need to step back, sometimes, from harsh reality and consider instead the potential for the epiphanies that lurk within the ordinary.

In a chaotic and troubled world, we need to find hope in creatures like Woody. We need to step back, sometimes, from harsh reality and consider instead the potential for the epiphanies that lurk within the ordinary.

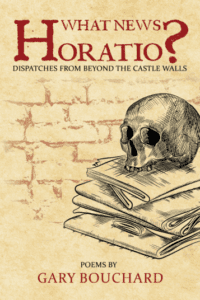

You can read about the Spanish speaking parrot—and many other interesting strange-but-true tales—in poet Gary Bouchard’s new book “What News Horatio? Dispatches from Behind the Castle Walls” (Slow Haste Press, $16.99).

Much madness is divinest sense, says Emily Dickinson, and Bouchard’s splendid poems drawn from the mystery—and possible holiness—of the everyday affirm this truth. In poems inspired by actual news headlines in a small local paper, Bouchard aspires to prove “Each day a headline, each headline a story, each story a character crying out like a dying Hamlet: ‘Report me and my cause.’”

The headlines and Hamlet

Gary Bouchard is a professor of English and the founding director of the Gregory J. Grappone Humanities Institute at St. Anselm College in New Hampshire. I reviewed his prior excellent book, “Twenty Poems to Pray,” in The Georgia Bulletin a few years ago, and the book became the basis for a successful adult education series. This new book retains Bouchard’s wisdom, but it is also humorous and sly, and serves as an antidote to so much of the truly bad news we hear.

As a professor, Bouchard specializes in Shakespeare, and like any Shakespeare scholar, he is particularly enamored with Hamlet. If you haven’t read the play in a while, recall that Horatio is an important character. It is Horatio’s idea to introduce Hamlet to his father’s ghost. It is Horatio who ponders the absurdity of mortality with Hamlet in the cemetery with Yorick’s skull. And it is the loyal and honorable Horatio—the only major figure in the play to survive—who is obligated to tell Hamlet’s tragic tale.

Using this metaphor of Horatio, the “reasonable speaker” as he is often called, Bouchard has crafted 24 poems all inspired by headlines of which Horatio might say, “So have I heard and I do in part believe it.”

The poems are arranged into three groups of eight, in sections titled “Guilty Creatures,” “Quintessence of Dust” and “Fortune’s Finger.”

Consider a few of the poems’ titles to get a sense of the book: “Bandit Jailed for Fifteen Years Robs Same Store Day After Release,” “Soccer Player Dies after Fatal Goal Celebration,” “Frantic Deer Comes in One Window, Goes Out Another,” and “Pope Stumbles in Church for Second Time in Three Days.”

I particularly like the poems about the deer and the Pope, for they typify Bouchard’s real aim in the book: wisdom and grace are delivered to us in both extraordinary and mundane ways.

Clearly, he achieves his purpose, and in poems that are often as funny as they are profound, Bouchard touches upon the fallible and fragile aspects of our nature consigned to wander for a while in a world that is always full of surprises. The poems here have a wry sense of humor, a keen ear for rhyme both subtle and pronounced, and an almost effortless blend of sound and sense.

The poem about the deer, for example, is a brilliant blending of an outrageous news story—a deer bursting through the window of a house—and the introduction of the Gospel to English King Edwin. Of the deer, Bouchard writes: “’til glass explodes and nature lunges in,/on four sharp hooves, blind and lost and frightened,/scampering in a fit of fur and blood/before lunging again towards the dark/reflection of its shadows in the night.” He ties this to King Edwin, who said upon hearing the Gospel, “Even so, man appears on earth for a little while; but of what went before this life or of what follows, we know nothing. Therefore, if this new teaching has brought any more certain knowledge, it seems only right that we should follow it.” As Hamlet makes clear in both his play and Bouchard’s poem, indeed, “There are more things in Heaven and Earth/than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

As for the poem about the Pope, for whom Bouchard clearly harbors empathy: “I am the humble front man for the Christ/in a world so torn and tortured in its fears/that it has become what it long has been,/a mixture rank of midnight weeds collected./So yes, I stumble.” The deer explodes; the Pope wobbles, but consider: “And yet I stumble,/like all holiness that must come down./There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,/rough-hew them how we will in ritual.” Whether it comes as triumphal shout or humbled whisper, Grace finds a way to touch us.

These are carefully crafted poems, evidence of both the poet’s bright imagination and his own love of poetry. Readers will delight in the allusions: there are plenty “shards of Shakespeare,” but other references that echo Edgar Lee Masters, Edwin Arlington Robinson and Ogden Nash. These are poems of joy, praise, awe, and wonder, all a testament that in a world gone mad, “There’s mystery in that bigness.”

Like many a character in the collection, the reader is left quietly amazed, much like Shakespeare’s Caliban upon waking, who cries to dream again.

Bouchard knows that language allows us to transcend the ordinary and savor a glimpse of the eternal. Or, as that parrot puts it, “And I learned to speak for the first time like a parrot should! Un idioma mas bonito! Un idioma romantico! My heart beat faster and grew larger. My feathers, I swear, turned brighter each day. O loro magnificos! Buenos dias mi regalo de Dios! Paraiso!”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.