Thomas Merton’s ‘Day of a Stranger’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published October 29, 2020

“This is the day that the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

As the months of the pandemic grind on, it becomes more difficult to embrace that essence of Psalm 118. I wish I could say that I have been glad in every day unto day of this ordeal, but like most people, I cannot. Impatience, irritability and even anger have crept into many of my days, and I am not always successful in driving out those emotions.

Do you know the classic children’s book “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day” by Judith Viorst? If so, you will remember the truth of this famous line from the story, “My mom says some days are like that … ”

Understanding the simple wisdom of that statement leads to acceptance, and acceptance can deepen our faith, even in the worst of circumstances, and even as day subsides into day.

We take, of course, most of our days for granted and even reduce them to pleasantries and clichés. “Have a nice day!” “How was your day?” “What a day.” Many times, we wonder more about other people’s days than our own.

In 1965, shortly after Thomas Merton had been allowed to live as a hermit in a small hermitage built on the grounds of Our Lady of Gethsemane Monastery in Kentucky, the Venezuelan journal Papeles wrote to ask if Merton would contribute a short essay on a typical day in his life. Merton obliged, and the essay, “Day of a Stranger,” was also subsequently published in The Hudson Review in 1967. In this short essay, so much of the essence of Merton’s vocation and message to the modern world is revealed. One day, Merton shows us, can be very important.

Seeing the extraordinary

The essay broadly accomplishes two practical tasks, which is probably why it was published in the first place. For one, it offers a sometimes-mischievous look at Merton’s new approach to his monastic vocation. Secondly, it provides a more literal look at a typical day in Merton’s life. Whether he wanted to be or not, Merton was famous, and the modern cult of personality wants to know as much as it can about the private lives of its heroes.

Yet as in almost everything Merton wrote, there is a depth of insight here that goes far beyond a simple sneak-peek. The essay embraces in a modern context the medieval idea that people are not so much defined by what they do, but by who they are. One hears the words “monk” or “hermit” and makes certain assumptions based on stereotypes; Merton takes pleasure in overturning those preconceptions.

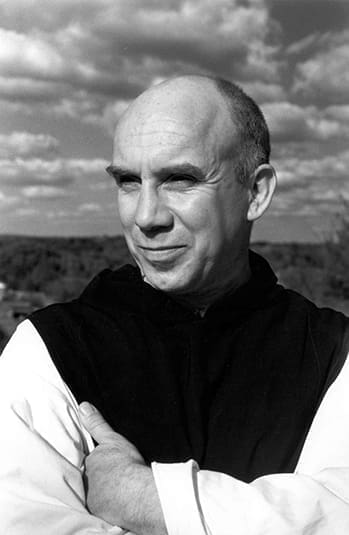

Trappist Father Thomas Merton, one of the most influential Catholic authors of the 20th century, is pictured in an undated photo. CNS photo/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Further, the essay criticizes the modern, technological world that reduces human beings to anonymous types or numbers. “I live in the woods,” Merton writes, “as a reminder that I am free not to be a number. There is a choice.” But this “choice” is not a matter of individualism, or liberty, or personal relevance; instead, it is about recognizing his own unique place as a “member of the human race.” Instead of emphasizing “me” Merton focuses on “we.” “I reserve to myself the right to forget about being myself … rather it seems to me that when one is too intent on ‘being himself’ he runs the risk of impersonating a shadow.”

As expected in a Merton essay, he also emphasizes the importance of silence, of listening, of being centered and whole. Yet like us, Merton has obligations. Despite his hermitage, he is still a member of a monastic community; he is still obliged “to visit the human race.” “The bell is ringing. I have duties, obligations, since I am a monk. When I have accomplished these, I return to the woods where I am nobody.”

Merton leaves it to the reader to determine that, despite his own protestations about the “institution” of the monastery, his work is important. His teaching in the novitiate, his chanting in the choir, his listening to the “trembling reader” who recites the pope’s recent message in the refectory: all of these are important and valuable tasks. They are as much a part of his “day,” as the more mundane chores of cleaning the coffee pot, chasing a snake out of an outhouse, and opening and closing windows depending upon the seasons. And they comprise part of the much larger “DAY” that is spiritual, that is never the same. Merton suggests that the trick is to see the extraordinary within the ordinary, and he implies that we can do the same, no matter our own vocation.

Lessons for the pandemic life

He finds this grace in literature, in art, in philosophy, and in theology. He describes the hermit life as “cool” in that it requires few decisions or transactions. He can declare, therefore, that in reality “This is not a hermitage—it is a house.” And within this home, he admits perhaps the most relevant truth of the essay to the pandemic life, “I am both a prisoner and an escaped prisoner.”

I love how this image applies to our current crisis, and the truth of it has lifted me out of innumerable difficult days. Think of all we have been given at the same time we have given up! Think of the pleasures of home, of being in and at home, of using the home we work so hard for but which so many of us rarely occupy. The typical worker, regardless of the job, is on an ordinary day gone from home longer than being in it. Home becomes merely a place to sleep. In the pandemic, home has become for us what Merton’s hermitage was to him.

Despite the happy solitude and silence, there are other sounds in the woods with Merton and the birds. For a man who wrote constantly about peace and race, there is always an argument against the forces of “the way that is not good, the way of blood, guile, anger, war.” Merton praises the silence of the darkness yet condemns the clamor in the darkness. There is the dark that seeks light, and the dark that squelches light. On a less profound level, Merton had the hermitage, but he also had to contend with the cheese-making enterprise of the monastery down the hill. We have to Zoom.

Throughout the essay, Merton strikes a humorous tone; he enjoys making fun of the act of describing his life, yet he is also able to be mystical—“In the silence of the afternoon all is present and all is inscrutable in one central tonic note to which every other sound ascends or descends.” Notice the wonderful pun implied by “tonic;” Merton is describing both sound and remedy.

Merton’s world of Cold War and racial strife certainly needed remedy. The entire essay is framed by the image of airplanes, some carrying passengers, others carrying nuclear weapons. The planes are a foreboding symbol, but this ominous image is balanced throughout the essay by Merton’s harmonious blending with the natural world around him and the liturgical world of the monastery below him. The planes bookend the piece, so that instead of writing solely about himself—a “stranger”—he is also placing himself in the company and communion of a world of other “strangers.”

At the center of it all, of course, is the Cross, upon which hangs the eternal redeemer of the lost, the lonely, the anxious, and the unknown. Thus, it is that Merton can end his day, sleeping peacefully under an Icon of the Nativity, even as “the metal cherub of the apocalypse passes over [him] in the clouds.”

“Day of a Stranger” is archived online at The Hudson Review, and appears in print in both “The Thomas Merton Reader” and “The Selected Essays of Thomas Merton.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.