A Catholic canceling of a culture of racism

By ASHLEY MORRIS, Th.M., Commentary | Published November 28, 2019

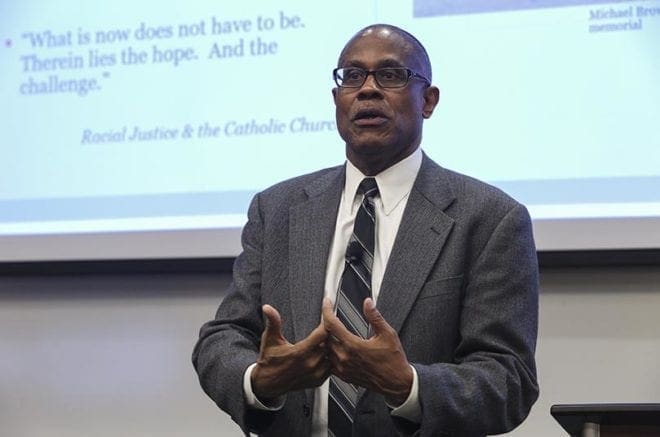

Father Bryan Massingale, a priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, Christian ethicist at Fordham University and author of “Racial Justice and the Catholic Church,” spoke at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology for its Howard Thurman Lecture on Nov. 7.

Father Massingale’s lecture, “The Catholic Church and the Struggle against White Nationalism: Missing in Action?” was sponsored by Candler’s Black Church Studies and Catholic Studies departments. It gave an uncompromising perspective on how white nationalism erodes the integrity of the church. Guests reflected on answering one question by the lecture’s end: will the Catholic Church serve as an effective ally in the struggle against this particular expression of racism?

Most Catholics are familiar with mortal and venial sin, the latter considered “everyday faults” and the former more egregious or grave sins that wound the soul more grievously than less serious offenses against God’s law. Our Protestant brothers and sisters, however, preach that sin is sin, and any offense against God and God’s law is grievous regardless of our human designation of its significance. To be fair, Catholics know and acknowledge that all sin requires an examination of conscience and the sacrament of reconciliation for expiation. Exercising that belief in a more tangible, practical way is hard to do when our collective catechetical formation presents the faithful at an early age with a hierarchy of transgressions. This is to say that while we believe a sin is a sin is a sin, we also concede that some sins are far more damnable, requiring more of our immediate attention and prayer than any other little wrongdoing, whatever “little” means to us.

The large elephant in this room of progressive iniquities is the sin of racism, a gravely dangerous and insidious evil that perpetually masquerades as a venial transgression among mortal infractions against God and humanity. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops recognized and named racism as a sin in its 1979 pastoral letter, “Brothers and Sisters to Us.” It stated that “Racism is a sin: a sin that divides the human family, blots out the image of God among specific members of that family, and violates the fundamental human dignity of those called to be children of the same Father.” The bishops continued by saying, “Racism is the sin that says some human beings are inherently superior and others essentially inferior because of race. It is the sin that makes racial characteristics the determining factor for the exercise of human rights. Indeed, racism is more than a disregard for the words of Jesus; it is a denial of the truth of the dignity of each human being revealed by the mystery of the Incarnation.”

Four decades later

A little more than 40 years since the letter’s release, racism is confronted again with another pastoral letter from our bishops, “Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love.” Their methodical message states that racism still exists, can be institutional and systemic and should be confronted and eradicated by the faithful. The letter cautiously approaches the lack of apostolic zeal among the faithful to fight this sin, as radical and missionary Catholic disciples of Christ. Our efforts against this evil often lack the energy, enthusiasm and righteous indignation given to protecting the lives of the unborn or the sanctity of marriage between a man and a woman. Perhaps this is why racism and its expressions—discrimination, prejudice, nationalism, supremacy and bigotry—continue to pervade human activity.

We readily champion the humanity in the lives of the unborn and the dignity of the sacred union between one man and one woman, but remain conspicuously passive in our respect of the human dignity and sacredness of all people regardless of skin color. In this sense, racism becomes more of an inconvenience than a sin; it is an unfortunate occurrence that, perhaps, the faithful believe will eventually disappear the more we recite Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Perhaps the faithful earnestly believe that the day has already arrived where children of different races can hold hands with one another, meaning we have arrived in a post-racial society where all enjoy respect and human dignity based on the content of their character. The recent influx of racist hate crimes and rhetoric across our nation speaks to a different reality, one that feels more like a recurring nightmare than the hopeful dream enunciated by Dr. King and echoed by others.

Racism remains prevalent, in part, due to a general inability to have raw and honest, action-oriented conversations about how this sin manifests in our everyday lives. Inauthentic activity in rooting out and eradicating this evil makes our fight against it more akin to therapeutic “check-ins” than conviction-based battles for our souls. Honest actions about the prevalence of racism make us uncomfortable because they force us to confront the ugliness of our past and present, as well as how we participated in purveying that ugliness or allowing it to fester.

As Father Massingale said, efforts of denouncing racism often fail to intentionally condemn and attack root causes and the perspectives that fuel it. These include nationalist ideals based on the perceived supremacy of one race over all others, privilege associated with not having to understand the lived experiences of others outside the prevailing culture and the preservation of the social relationships and comfort of the prevailing culture over what is right and just as outlined by the Gospels.

Father Bryan Massingale was the speaker for the Nov. 7 Howard Thurman Lecture at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. The lecture was entitled, “The Catholic Church and the Struggle Against White Nationalism: Missing in Action?”

Openly condemning white nationalism and white privilege, therefore, appears to be an attack against white people, history, and culture, what we understand, consciously or unconsciously, to be the “norm” in the United States. The response to this attack on one’s personhood and culture runs the gamut from guilt, shame, anger, hostility, bitterness and retributive acts of violence. All are emotional responses from the fear of losing what we consider “normal.” It was not long ago when pundits lashed out at the idea of depicting the Palestinian Jewish Jesus and/or the Turkish St. Nicholas (Santa Claus) as non-white. It seemed more important for us to keep and value the “normal” depictions of both figures despite them being historically questionable.

That sense of normality has roots in what the bishops spoke against in their 1979 pastoral letter on racism and reiterate in Open Wide Our Hearts: “… sin that says some human beings are inherently superior and others essentially inferior because of race.” Thus, racism continues to be a tumor maligning the body of Christ, because challenging and condemning the racist roots in what we deemed normal is to challenge what makes us comfortable, and perhaps ultimately complacent. The challenge and condemnation is not against white culture, but maintaining the idea that the white race in particular is superior to all other races and that sense of superiority is necessary for the safety and stability of the entire world at the expense of all other races. The challenge and condemnation is against the notion that one race should dominate others because of a supposed sense of superiority. The challenge and condemnation is against the practice of treating black and brown-skinned individuals as less than because we are not white, and conversely, must be “abnormal.”

We cannot stand to believe or remain comfortable intricately connecting culture with racial supremacy, that one is better than all based on a social construct attached to the levels of melanin in the body. The fight is not against white culture, but against a toxic belief that all other cultures are abnormal, inferior and less than. That perspective exists and indelibly stains all of humanity. Do we Christians want to associate ourselves with such toxic, sinful notions? Probably not, which makes it imperative that we pray for the courage and strength needed to categorically condemn all that seeks to separate us from the love of God and one another.

We cannot remain comfortable and complacent in our Catholic Christianity if members of our human family—the same members Christ commissioned us to make disciples of—continue to suffer from degradation, discrimination and death because a 21st century society view still holds us as less than human because of skin color. When we aggressively fight for the human dignity of the unborn while passively or haphazardly acknowledging the human dignity of the living, what suffers and dies within each of us? Christ was clear on many occasions that the cost of discipleship is a heavy price to pay for the sake of God’s Kingdom. To paraphrase from Matthew’s Gospel—those who lose their lives for Christ will find eternal life in him (Mt. 16:25).

It is important to remember Father Massingale’s words that racism in general and white nationalism in particular erodes the church’s integrity, and that affects everyone. As members of the body of Christ called to be intentional about radical, missionary discipleship, our efforts fall flat when we fear what could be the increase of Christ at the decrease of our own comfort and sense of entitlement. The body of Christ suffers when all of its members suffer from the sin of racism. It is imperative that we energetically condemn and fight all iterations of this evil as the mortal sin it is.

We thank God for the vision of our bishops and their letters against racism, but the responsibility of actively fighting against this evil is the cross that all baptized Christians must bear to follow Christ. Moreover, fighting this evil requires far more immediate attention, prayer, conviction and action than we currently attribute to it.

Mr. Ashley Morris, associate director of the Office of Intercultural ministry, may be contacted at amorris@archatl.com.