A tribute to Stan Lee and creative people

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published November 22, 2018

One of the most difficult events we can ever experience is the sudden loss of someone close to us.

As you know, Mary Anne Castranio, executive editor of The Georgia Bulletin, died suddenly a few weeks ago. I am still stunned by her death.

Seven years ago, when Mary Anne gave me the opportunity to write a regular column for the newspaper, neither she nor I had any idea the ramifications that would come from this work. By graciously allowing me to write for you over all these years, Mary Anne opened so many new possibilities for me for which I will be forever grateful.

This is the first column I’ve written since Mary Anne died, and for the first time in many years, I won’t be sending it to her. I won’t receive from her a wise and witty reply. Though the work of The Georgia Bulletin will be managed by a host of talented and dedicated people, I know I speak for all at the paper when I say that Mary Anne will be deeply missed. The paper published a beautiful obituary for Mary Anne after her death, and I can only add to that eloquent tribute a sincere “Amen.”

Mary Anne was a media figure, so her work meant a great deal to people who for the most part never met her. Such is the case with all creative people who dedicate their lives and work to the fulfillment and enrichment of others. They devote everything to our education, to our entertainment, to our understanding and appreciation of the world. They give so much of themselves that we often feel we know them, and when they leave us, the world seems an emptier place.

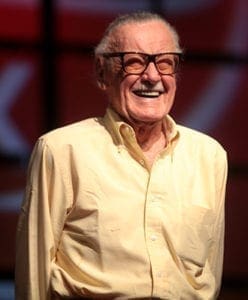

Surely this is true of the recent passing of the genius Stan Lee, the visionary leader of Marvel Comics, who for decades oversaw a publishing and media phenomenon that enlightened, enthralled and delighted fans all over the world. Lee was preceded in death this summer by one of his most important collaborators, the gifted artist Steve Ditko.

You would live under a rock indeed if you didn’t know the names The Fantastic Four, The Uncanny X-Men, The Incredible Hulk, and The Amazing Spider-Man. Even if you don’t follow the comics, which long ago ceased to be a diversion for children and entered the realm of respected art, these characters created by Stan Lee and his Merry Marvel Bullpen are part of the culture’s collective consciousness.

A vital part of America’s pop culture

Stan Lee, the writer, editor and publisher of Marvel Comics, died Nov. 12 at age 95. Photo by Gage Skidmore

Though it is difficult to imagine a time when the comics did not exist, they might very well have ceased to be were it not for Stan Lee’s leadership. In the face of growing public criticism, fifteen comic book publishers went out of business in 1954. In response, Lee cooperated with the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, a self-imposed standards board that regulated the content of comics and ensured they would remain a vital part of American popular culture. Ironically, Lee was also the one who first challenged the Comics Code, when in 1971 he published a series of anti-drug issues of The Amazing Spider-Man.

Yet Lee always went his own way. As a schoolboy, his great ambition was to sing. Told by his teachers that he had no musical aptitude at all, he was confined instead to “the listening room.” There, he let his imagination go to work. At age 16, he was already working as a gofer and writer at Timely Comics. When the United States entered World War II, he joined the Army and became one of only a handful of people who have ever been given the military designation of Playwright; two other notables who received the same distinction were filmmaker Frank Capra and Dr. Seuss.

When Marvel Comics began in 1960, Lee also went in a different direction. Unlike so many other comic book characters, Lee’s heroes were real people with real problems. They were often neurotic, anxious about their abilities, and nervous and alone among others.

None of the Marvel heroes exemplify this realism and anxiety more than teenager Peter Parker, who in 1962 suddenly found himself a lonely but brilliant science student transformed into the Amazing Spider-Man.

A lasting hero

In keeping with Lee’s frequent encounters with serendipity, Spider-Man—co-created with Steve Ditko—was never meant to last. He was slated to appear in the final issue of Amazing Fantasy, a book to be cancelled after its 15th issue. Readers were so taken with the character that the issue was a smash, and a few months later Spider-Man reappeared in his own magazine. He’s been with us nearly sixty years—in multiple comic variations, television shows and feature films. He’s so engrained in popular culture that many people insist he is real; a familiar sight in New York City, for example, is the bumper sticker that proclaims “This car protected by your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man.”

Of course, the Marvel Universe isn’t real, but it is a wholly convincing fictional world, a world that J.R.R. Tolkien referred to as “sub-creation.” In a successful sub-created world, the artist is given the privilege of sharing in the joy God Himself must have felt in making the primary Creation. And within the sub-created world, the artist can reveal what Tolkien called the Eucatastrophe, “the joy of the happy ending, joy beyond the walls of the world.”

Stan Lee’s Marvel Universe is filled with evil. It contains loss and sorrow and death. Yet in issue after issue, in title after title, across half a century, the comics reveal also the joy of redemption, the persistence of heroism for the common good, and the real possibility of resurrection. Stan Lee was not a Catholic, but as a native New Yorker, he had a keen appreciation for both his own Jewish faith and the Catholicism that was all around him. There are Catholics throughout the Marvel Universe, none more explicitly than Daredevil, whose real identity is Matt Murdock, a Catholic.

Marvel’s life lessons

Those who too easily dismiss the comics as pulp fiction or the product of a low-brow culture deny themselves not only the pleasures of brilliant illustrative art and design and tales told with swagger and daring. They also miss out on the lessons these stories teach us. This is particularly true in Stan Lee’s Marvel Comics, where even heroes are flawed, where even those with super powers must deal with the problems that beset us all, from the petty and trivial to the difficult and profound. One of Lee’s favorite stories in the earlier days of The Amazing Spider-Man involved the problem of how Peter Parker could get his costume cleaned without being exposed as Spider-Man!

As much as any modern artist, Stan Lee dealt with the problem of identity. Peter Parker is Spider-Man, but he is also Peter Parker. Like Eliot’s Prufrock, who “prepares a face to meet the faces that he meets,” or the Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby who “wears a face that she keeps in a jar by the door,” Peter constantly has to reckon with the multiple aspects of his singular nature. His dilemma is one that we all face: Who am I? Why has this happened to me? How can I find positive meaning through crisis and suffering?

What Peter Parker learns, what indeed becomes the motto that informs the entire Spider-Man saga, is a powerful lesson that all of us should strive to remember: “With great power there must also come great responsibility.”

And yet, in the end, The Amazing Spider-Man and all of Stan Lee’s other characters aren’t meant to be solely an invitation to ponder the mystery of life. They are fun. They offer escape and respite from the world even as they show us both the good and bad inherent within the world.

On the day Stan Lee died, my sons and I visited one of Atlanta’s best known comic shops to pay our respects. We bought a few comics and talked to others who were in the shop for the same reason; they wanted to pause and say thank you to the man whose work had meant so much to them, to their children, even to their own parents.

Lee lived a good, long life and died at the old age of 95. He was a wonderful family man, devoted to his daughter and to his wife Joan, who died last year after 70 years of marriage to Stan.

Lee might have ended this tribute himself with one of his favorite sign-offs—either “Excelsior!”, which means ever onward and upward, or “‘Nuff Said”—but I think it more appropriate to close with the words with which he ended the epilogue to the first Spider-Man anthology he edited in 1978. It’s a fitting reminder of the Communion of Saints and the souls of all our faithful departed: “Thus, as we’ve said to each other so many times in the past, this isn’t really goodbye; it’s just so long—till we meet again with more fun and fantasy culled from the never-ending living lore which is the wonderful world of Marvel.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.