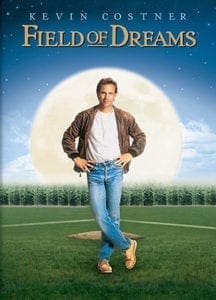

‘Field of Dreams’ shines in the light of faith

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published May 19, 2017

If Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” is perhaps our most misunderstood poem in American literature, then “Field of Dreams” must be our most misinterpreted baseball movie.

Frost’s famous closing line, “I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference,” is persistently misread as a tribute to individualism and nonconformity, rather than what it really is, a lament for what might have been.

Frost’s famous closing line, “I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference,” is persistently misread as a tribute to individualism and nonconformity, rather than what it really is, a lament for what might have been.

Likewise, the line from “Field of Dreams,” “If you build it, he will come,” which has entered the American language as a sort of colloquial testament to certainty, is now taken as a homespun acknowledgement of self-reliance and positive consequence.

Both lines, and both misinterpretations, are as American as they can be, and even when taken out of context, each evokes a wistful memory or even perhaps a smile.

Yet “Field of Dreams” deserves better. Far from being seen only as a sweet and simple film about the power of dreams, perseverance and the human spirit, “Field of Dreams” needs to be viewed from a theological perspective. For the Catholic audience, this means seeing the film as a meditation upon the mystery of purgatory.

Before the movie adaptation in 1989, “Field of Dreams” was an interesting and compelling novel titled, “Shoeless Joe,” in reference to the famous ballplayer Joe Jackson, who was among the eight Chicago White Sox permanently ousted from baseball for his supposed role in throwing the 1919 World Series.

Of his book, author W.P. Kinsella has said, “I have to disappoint fans by telling them that I do not believe in the magic I write about. Though my characters hear voices, I do not. There are no gods; there is no magic. I may be a wizard though, for it takes a wizard to know there are none.”

Those reflections about his work represent precisely why the film adaptation of the novel is superior to what is indeed a fine book. The filmmakers—and the movie is a masterwork of collaboration between director, cast and crew—approach the material with the assumption that there is a kind of magic in the world, that there is a God, and that there exists an underlying order the Catholic refers to as mystery.

The specific mystery in “Field of Dreams” is purgatory, which many Catholics tend to overlook, particularly in the midst of the church’s current emphasis upon evangelism and mercy. To me, purgatory actually represents an especially beautiful mercy, for it is inextricably joined to hope.

Consider this excellent summary of purgatory from The Catholic Encyclopedia: “The souls of those who have died in the state of grace suffer for a time a purging that prepares them to enter heaven and appear in the presence of the beatific vision. It is an intermediate state in which the departed souls can atone for unforgiven sins before receiving their final reward. The final testing of one’s faith is not a punishment but one of response.”

That statement should have been used to publicize the release of the film! Instead, one of the official taglines for the movie was, “If you believe in the impossible, the incredible can come true.” It’s less eloquent, but also less vague: of “Field of Dreams” and its connection to purgatory, a better tagline might be, “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Iowa farm turned baseball field

I’m assuming that you know the story, but for the sake of refreshment, here is a quick plot summary:

Ray Kinsella is a happily married Iowa farmer. Raised by his father, who played a little baseball and who taught his son a love of the game, Ray rebelled and in college was swept up in a fervor of 1960s radicalism and idealism. As a result, Ray and his father were estranged, and the father died without reconciling with his son. One evening in the cornfields, Ray hears a strange voice that implores, “If you build it, he will come.”

As time goes by, Ray is given a series of visions that convince him he should plow under his corn, build a baseball diamond, and await the return of Shoeless Joe Jackson. Ray gets part of it right. The field is built, and it is beautiful. Shoeless Joe does indeed come to play.

Yet Ray’s adventures are just beginning. The voice next implores him to “ease his pain.” Hence, Ray finds himself in Boston, kidnapping the writer Terence Mann and taking him to a Red Sox game. At the ballgame, both Ray and Terence see a message on the Jumbotron, exerting them to go in search of Archie “Moonlight” Graham, who played in one major league ballgame without getting a chance at bat. Told to “go the distance,” Ray and Terence find Moonlight Graham, who it turns out had retired from baseball to become a small town doctor. Moonlight died in 1972, but through a series of fantastic events, Ray has a vision of the older man.

The next day, as they travel back to Iowa, Ray and Terence pick up a young hitchhiker, a ballplayer, whose name is Archie Graham. In the end, as the local bank tries to foreclose on the farm, Shoeless Joe is joined by a legion of former ballplayers, including a man who turns out to be Ray’s father. Moonlight gets his chance to bat, Terence is summoned off into the cornfield and happily vanishes, and Ray gets to play catch with his estranged father.

The film ends with an image of thousands of cars, their headlights slicing the Iowa darkness like souls, all bound for the mystical ballpark Ray has built.

Something beyond the cornfield

A summary really doesn’t do the movie justice. “Field of Dreams” is a beautiful film, evocative and lyrical, and marvelously cast and performed. It’s one of my perennial springtime films, one I watch and enjoy every year. Yet my growing appreciation of the film’s purgatory context has enriched my annual screening.

I doubt the filmmakers set out to make a meditation upon purgatory, and it’s certain that W.P. Kinsella puts no stock in it, but to appreciate fully any work of art means casting aside authorial intent and relying instead upon informed subjectivity.

“Field of Dreams” is not just a baseball movie, though of course it has to channel its larger themes through baseball, because baseball, unlike most other sports, exists outside of time. Purgatory, too, exists outside of time, though within the communion of souls and the church. We can’t measure it in terms of days or years; just as an inning could conceivably go on forever, so with our time of atonement in purgatory.

Each character on Ray Kinsella’s Iowa baseball field is atoning: Shoeless Joe for his suspected role in a gambling conspiracy, Terence Mann for his resentment and remorse, Moonlight Graham for denying the hope of a second chance, and Kinsella and his father for their estrangement. Yet in their purgation, each one is given mercy beyond measure. Jackson and all the other ballplayers get to play the game they love; Terence Mann is given the opportunity to be once again writer and philosopher; given the gift of choice, Moonlight Graham gets to bat and practice medicine; the Kinsellas are reconciled. That all of this occurs on a baseball field, in an Iowa cornfield, in the middle of nowhere is a beautiful affirmation of the mystery of purgatory.

In Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” the souls in hell know that they are lost. They are explicitly told, upon entering, to “abandon all hope.” Those in purgatory have the hope of eternal redemption, though they do suffer from desire. They all wish for little things of life—a train ride, a smoke, a kiss. Yet the characters in “Field of Dreams” know that there is something beyond the baseball diamond, in those mysterious waves of corn.

On more than one occasion, a character in the film poses the question, “Is this heaven?” “No,” answers Ray, “it’s Iowa.” I like to think Ray knows better.

In his beautiful ode to the union between art and the eternal, Keats writes in “Ode on a Grecian Urn” that “heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.” The characters undergoing purgation on that Iowa baseball field know one aspect of their collective redemptive suffering; they know that at some point their games have to stop. Yet they are all beginning to sense as well that they are being readied for something greater, something that in fact will never end.

St. Paul reminds us that “Now we see through a glass darkly; then, face to face. Now we know in part; then we will know even as we are known.” I think this is the essence of both “Field of Dreams” and purgatory.

There are two wonderful moments near the end of the film where the living and the dead connect with each other; one when Moonlight Graham chooses to leave the field to save life, and the other when Terence Mann is invited into the corn.

The very day I wrote this piece, in a marvelous synchronicity, the Gospel reading for the day just happened to be, “Do not let your hearts be troubled. You have faith in God; have faith also in me. In my Father’s house there are many dwelling places. If there were not, would I have told you that I am going to prepare a place for you? And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back again and take you to myself, so that where I am you also may be” (Jn 14:1-3).

We are often implored to pray for the holy souls in purgatory. The vision of “Field of Dreams” poses a question the church has often asked itself: are those souls also able to pray for us? This is a great mystery of our faith. Perhaps if we build upon it?

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.