A fundamental rite of passage in the love of popular music

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published February 24, 2017

My three earliest memories are all from the year 1969.

I vividly recall being positioned in front of our 16-inch black-and-white television to watch Neil Armstrong step upon the moon.

I remember watching awestruck—this time on a new color set—the very first episode of “Sesame Street.”

And I still remember, in between news flashes about “gorillas” in Vietnam, hearing on Atlanta’s hip FM 100 radio station the glorious music from the Beatles’ new LP “Abbey Road.”

I still think astronauts are cool. I still think Kermit the Frog is really neat. I don’t think about either of them very much anymore. But the Beatles, well, that’s a different story.

When I was a child, the Beatles were everywhere; it was difficult to imagine daily life without their music always in the background. Yet the band broke up, and the ’70s happened, and then tragically in 1980, on Dec. 8—the solemnity of the Immaculate Conception—John Lennon was shot to death.

And the Beatles came back. I was 13, and like millions after Lennon’s assassination, I went nuts again for the Beatles. I got every record they ever made; I read everything about them I could find; I got to see “A Hard Day’s Night” in the wonderful old Screening Room in Lindbergh Plaza. To this day, I still go through phases of Beatlemania.

Photo of the Beatles from a May 1, 1965, issue of Billboard magazine.

For me, as for many others, the Beatles were most important because they sparked a lifelong passion for music. I think that if children meet the Beatles early enough, they are naturally inclined to want to know more not just about the band, but music in general. I know that is true for my boys, one of whom is going through his first Beatles craze now. My other son is more inclined to the Rolling Stones. Some rivalries never fade.

Catholic connections

I always knew that there were Catholic connections to the Beatles; they were, after all, products of Irish heritage and culture in Liverpool. Yet I didn’t know the full story until my older boy made a PowerPoint presentation about the band. In his slide for Paul McCartney, he proudly informs his audience that McCartney is a Roman Catholic.

Now I won’t presume to make conjectures about McCartney’s religious faith, but I don’t think he is a practicing Catholic. Still, the man who wrote “Let It Be,” which might rightly be heard and sung as the greatest hymn for the Blessed Virgin Mary of the 20th century, obviously retained a good deal of Catholic identity into adulthood. McCartney was, in fact, baptized as a Catholic and was raised in the Catholic Church before his mother’s death.

Like McCartney, George Harrison was also baptized a Catholic, and he too was raised in a devout Catholic home. Though Harrison would later embrace Eastern meditation and mysticism, he remained throughout his life one of the most deeply spiritual musicians of our time, a fact fully acknowledged by Martin Scorsese in his beautiful film tribute to Harrison’s life.

McCartney and Harrison might not have practiced a ritualized Catholicism, but the fact is they certainly lived the truth and grace of their Catholic baptisms, both in the wonderful music they gave the world, and also in the benevolent works they performed for others.

Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh became the prototype for all the musical benefits for hunger and poverty that have followed, and McCartney has always donated his talent for others, including music education and compositions for liturgical settings, most notably a piece dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Even Lennon, who reconciled himself to his Irish Catholic heritage in the years before his death, contributed generously to the cause of Catholic civil rights in Northern Ireland. Lennon was particularly empathetic to the Irish Catholic priests who were working for a peaceful solution.

As I have said, the initiation into the music of the Beatles—which to me is a fundamental rite of passage in the lives of many young people—ultimately leads to the discovery of other music, and the music that we love when we are young remains with us throughout our lives.

I was a high school and college student in the 1980s, which was a particularly bland era for popular music, unless you looked underground. And the underground music scene—we called it alternative, or college radio—in the 1980s was fantastic.

As a native Georgian, I got into the Athens music scene from the beginning, and I still adore the earlier work of R.E.M. I’ve still got many of the “mix-tapes” I made in the ’80s, all of them crammed with songs from British and American bands that at the time seemed so crucial to existence. Many of those songs now make me wince; some of them, however, retain their greatness. At last I know the answer to the question we used to ask of our parents: will our music ever be called “oldies”? The answer, of course, is yes.

Two ’80s bands influenced by the faith

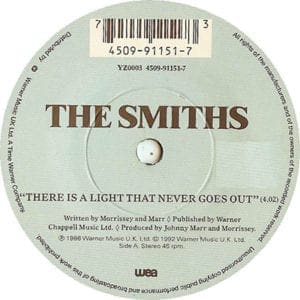

Besides R.E.M., in my experience there were two bands from the 1980s that were absolutely essential listening. Their posters adorned the walls of every hip college dorm room. Their seven-inch singles, cassette tapes and even exotic CDs cluttered the bedrooms of all who suffered under suburban angst. One was the Smiths, from Manchester, England. The other was 10,000 Maniacs, from the New York Rust Belt. Both remain great, both have strong Catholic roots, and the enduring legacy of each says a great deal about the persistence of a Catholic childhood.

Besides R.E.M., in my experience there were two bands from the 1980s that were absolutely essential listening. Their posters adorned the walls of every hip college dorm room. Their seven-inch singles, cassette tapes and even exotic CDs cluttered the bedrooms of all who suffered under suburban angst. One was the Smiths, from Manchester, England. The other was 10,000 Maniacs, from the New York Rust Belt. Both remain great, both have strong Catholic roots, and the enduring legacy of each says a great deal about the persistence of a Catholic childhood.

The Smiths are recognized today as one of Britain’s finest bands. In the span of less than four years they created a body of work that remains unrivaled by any British group since the Beatles. They have transcended popular music and have become in Britain a cultural icon.

The band was formed by Steven Patrick Morrissey and Johnny Marr, both Irish Catholics from Manchester, and both the product of Manchester’s rather severe parochial schools. Morrissey, in particular, had an imagination and identity inseparable from his Catholicism. He received all the sacraments of initiation and was immersed in the ritual and atmosphere of a uniquely Irish Catholicism.

Though he ceased practicing the faith as a young adult, he has in middle age made frequent hints that his Catholicism is integral to his identity. “It sears you,” he has said of the faith, and he doesn’t mean in only a cultural way. His more recent music has revealed a spiritual aspect of himself that I always suspected was there, especially in songs such as “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out.”

I still harbor hope for Morrissey’s full return to the church. After all, his great hero is Oscar Wilde, and Wilde was a famous deathbed convert to Catholicism, the only religion he said was worth dying in.

Though the Smiths’ Catholic influences were subtle, they were at the fore of 10,000 Maniacs, particularly when singer Natalie Merchant was in the band. Merchant left the group in 1993, but the band continues to record and perform, even in the old tradition of playing gigs in Catholic parishes.

At the height of 10,000 Maniacs’ fame in the late 1980s, Catholic sensibility and even iconography surrounded the band. Songs frequently alluded to Catholic devotions and rituals. Album art referenced Catholic imagery. The band’s breakthrough LP, “In My Tribe,” was full of passionate songs about a variety of social issues—illiteracy, child abuse, alcoholism—and at the heart of it was a knowing appreciation of Catholic identity. Though it was the first fully digital recording, it sounded as if it could have been made and performed in a parish fellowship hall. The band even named their publishing company Christian Burial Music.

Merchant experienced a profound life change when she became a mother, and motherhood ignited her musical career. By most accounts, she is writing and recording some of her finest music now. She has also made a return to the church. Baptized a Catholic as a child, and raised in the church until she became a teenager, Merchant always seemed to regret her lack of an education in the faith. She knew the rituals but not the reasons behind them. Like Morrissey, she knew the rules, but not the spirit and truth in which those rules are formed, nor the grace with which they are to be observed.

Recently, she has composed and arranged music for liturgical settings and has found a spiritual retreat in a Spanish monastery.

My son has many interests in his life now, and I’m happy that the Beatles are one of them.

I’m most pleased, however, at how deeply he has embraced his role as an altar server. He serves at every Mass he possibly can, even when he’s not required, and he serves at both our main parish and our Hispanic mission. As a result, he hears a lot of different music.

I know he’s happiest, however, when he’s in his room, listening to those old Beatles records of mine at full volume. I watch him, sometimes, as he dances and sings along. His red and white cassock and surplice hang on a hook near his turntable. I hope he never forgets that his service and his music can go together, that, in fact, for the Catholic imagination, they should never be apart.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.