The breathtaking chant of ‘Salve Regina’ is a call to joy and devotion

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published June 23, 2016

The recent passing of Father Anthony, the beloved priest and monk at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, has brought back many fond memories for me, remembrances of people and experiences all connected to one of the most special places in our archdiocese.

I am not alone in my deep sentiment for “the monastery,” as so many of us simply name it. Indeed, some of my closest friends—the Kramers of Decatur—don’t hesitate to refer to Holy Spirit as “our monastery,” and the excellent scholarly work Dewey and Victor have done related to the abbey certainly entitles them to that claim.

I first visited the monastery half my life ago, when I was in the process of becoming a Catholic. Early one summer morning, before dawn, I drove down to Conyers, not really knowing what to expect. My imagination, as well as my spirit, had been sparked by a reading of Thomas Merton’s “The Seven Storey Mountain,” and I suppose I expected to find at the monastery at least some resemblance to the mysterious life Merton portrayed in his book.

I discovered mystery for certain. I also discovered salvation. Had I any doubts about becoming a Catholic at that point in my young life, they were immediately dispelled when I entered the cool dark of the abbey church, knelt in quiet prayer, and then was immersed in the reverberation of the most beautiful music I had ever heard.

No one forgets the first time they hear Gregorian chant, the simple beautiful liturgical music popularized by Pope Gregory in the fourth and fifth centuries. To hear it, particularly in a live and liturgical setting as at the monastery, is to be plunged into an awareness of the eternal. As I listened to the monks early that morning, and as I returned to the church throughout the day for the other communal prayers, my soul elevated and my senses thrilled to the beauty of this music that seemed to come from some place outside of time. I remember thinking that this must be what heaven would sound like.

At that time, I was a struggling unemployed graduate student, so broke that I parked my car two miles from Georgia State University so that I could park for free. My daily walk to school took me past Sacred Heart Church. Even though I was reading Merton, and thinking about becoming a Catholic, I was afraid to enter that odd-looking building on what native Atlantans still refer to as Ivy Street. My trip to the monastery gave me the courage I needed, however, and one day I opened the door to the church and attended my first Catholic Mass. That afternoon, I found myself talking to a priest about becoming a Catholic. A year later, I entered into full communion with the Church at the little Chapel of Our Lady of Good Counsel at the Georgia State University Catholic Center, with two beloved Catholic professors serving as my sponsors.

Jesus Christ comes to us all in many different ways. For me, he revealed himself fully through my imagination. We must never discount the importance of art and culture to faith. Jesus is fully present in the sacraments, but for those of us unable to yet receive sacramental grace, we need to first be invited. My invitation came by way of the richness of the Catholic aesthetic and intellectual tradition, and the chant of the monks was the final piece of the summons.

I was living with my parents at the time, as I could not afford to pay rent, and I had to be secretive about my conversion. All young men smuggle contraband into their parents’ homes; in my case, the contraband just happened to consist of rosaries, prayer books, a missal and a large assortment of miniature saints, Marian statues, and crucifixes. At last among my smuggled goods was a CD of Gregorian chant, which I listened to on headphones in the deep of night when no one would know.

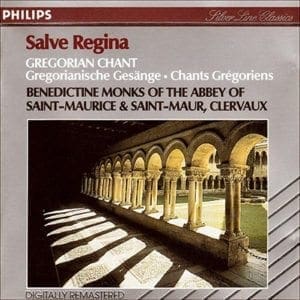

That recording became very special to me, and I consider it today as one of the most influential records I have ever heard. I am referring to an album of Gregorian chant that was recorded in 1959 at the Abbey of Saint-Maurice and Saint-Maur in Clervaux. The record, which was not made in a studio but rather in an actual liturgical setting, features the plainchant of the Benedictine monks at the abbey. It endures today as the greatest recording of this unique music ever made and deserves a place in every Catholic’s record collection. The CD remains in print, on the Philips label, under the title “Salve Regina.” An expanded two-disc version has been released, but the single 46-minute disc remains, I think, the best way to appreciate this liturgical music.

This is music not meant for background listening, not intended merely to accompany prayer. This music is prayer.

As David Hiley writes in the liner notes to the disc, “plainchant was not ‘composed’ for a modern music-loving public, seeking variety and profundity of experience. It developed as part of the ceremonial of the Medieval church, an aid to worship, adding solemnity and splendor to ancient rituals. We take it out of this context at our own risk and must consequently hear it in imagination back in its proper setting.”

This quality of authenticity is above all what makes the recording so special. You may recall that in the 1990s, there occurred a renewed fascination with Gregorian chant, due largely in part to the recording “Chant” that was made by the monks of Santo Domingo de Silos in Spain. While that hugely popular record was made using sophisticated production techniques, the music on “Salve Regina” is almost completely real. Few edits were made and no artificial manipulation was used. In fact, throughout the recording, the listener can occasionally hear other sounds in and outside the abbey church, including birdsong. Listening to the recording then is actually like being in the church itself, and the natural echo literally resounds exactly as it would in an old stone church.

Of the 17 selections on the disc, most of them are prayers and hymns to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The piece that opens the program, “Magnificat—Tu es Pastor Ovium,” is perhaps my favorite, and it sets the tone for the entire record. While most plainchant is unaccompanied, the monks here use an unobtrusive organ to establish the initial modal line upon which the chants revolve.

Like the organ that serves as an invitation to prayer, many of the chants begin with a solo voice that is then joined by a larger chorus of voices. This approach underscores one of the primary aspects of monastic life, that of the individual who lives not for himself but in community and communion with others.

Above all, the monks’ praise becomes the listener’s praise. In their prayer for the universal Church and the world, the monks also pray for those who are listening, and the listener in turn joins his prayer to that of the monks.

Many people unfortunately have the misconception that “all chant sounds the same,” and that mistake comes from the more contemporary recordings that lack both the authenticity of setting and the sincere belief of those who sing. A secular choir, for example, uninformed by monastic life, true devotion to the sacraments, and sincere belief in Christianity may be able to make a beautiful sound; they cannot, however, achieve the sheer transcendence the monks do.

Several selections on the disc conclude with a series of “O” refrains; most notable among these are “Ave verum Corpus” and the title track “Salve Regina.” When the monks conclude the “Salve Regina” with “O clement; O pia; O dulcis Virgo Maria,” they reach what is perhaps the pinnacle of the entire recording, an expression of joy and devotion so profound that even after years of listening to the record, I become absolutely transfixed.

I think you will come to love this music as well, and if you do not know it, I urge you to make it part of your daily prayer. The CD booklet includes the Latin lyrics to all of the chants, which provides a useful way to feel more connected to the monks’ prayer.

As I was preparing to write this piece, I had the unexpected pleasure of sharing this beautiful music with my son Nicholas, who along with his brother had been quite fond of Father Anthony. Nicholas had heard the music playing from another room and came to the office to ask me what it was. Without any invitation from me, he sat in a chair, listening. After a few minutes, he drew the shades and sat listening in darkness. Then, obviously moved, he gently raised one blind and let in the light.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.