King, Merton profoundly sensed providential, urgent time

Published January 22, 2015

1968 is arguably the most tumultuous year in modern American social history.

That terrible year began with the massive Tet Offensive in Vietnam, a series of coordinated attacks by the Viet Cong that resulted in the deaths of thousands and provoked a radical reversal of public opinion in the United States about the war, even as combat operations continued to escalate. In the wake of Tet, on March 31, President Lyndon Johnson announced his decision not to seek re-election.

‘Grievous losses’

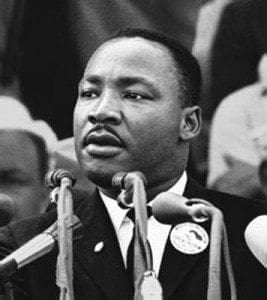

On the fourth of April, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis; many Americans learned of his death from presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, who urged the country to remain peaceful in the wake of the tragedy.

Shockingly, only two months later, Kennedy himself was shot and mortally wounded on June 5 in Los Angeles. He died early the next morning; his death, along with that of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, five years earlier, seemed to herald the end of an unprecedented era of American idealism, resolve and moral certainty.

At the end of the year, between a temporary halt to the bombing in North Vietnam and a manned spacecraft orbit of the moon, another death occurred. It was a grievous loss for those who knew him, but one that passed almost unnoticed at the end of a year in which the country had dealt with almost more than it could bear.

It was, like his life, a quiet death, but the consequences of it have reverberated across the subsequent decades.

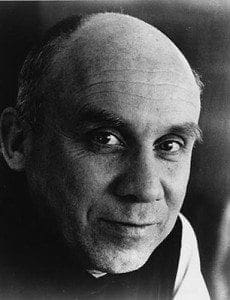

Thomas Merton’s accidental death on Dec. 10, 1968, in Bangkok, Thailand—coupled with the loss of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—ended forever the speculation that these two great spiritual leaders might have together changed the course of history.

Though King’s death in April closed the possibility for a personal encounter, Merton’s own death was a blow to the legacy King had left; even after King’s murder, Merton had hoped he might work more closely with those allied with King’s vision of nonviolent pacifism.

What might have happened if Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton had actually been able to meet, as they had planned? Readers and admirers of both men have often wondered what, if anything, might have gone differently in 1968 and beyond.

Two who called for faith put into action

Merton and King were certainly aware of one another. Merton had read, in his words, “from cover to cover” books by King that were sent to him at his monastery in Kentucky.

Merton was a correspondent with two Atlanta Quakers, John and June Yungblut, who had been arranging a retreat and meeting with King and Merton in the spring of 1968 at the Abbey of Gethsemani. Sadly, King was killed shortly before the meeting could be held.

Though there were important differences between King and Merton—race and religious perspectives are obvious—both men were deeply devout Christians who believed that faith had to be put into action.

The key connection between Merton and King is each man’s understanding of “crisis.” According to Albert J. Raboteau, “Merton and King had a profound sense that they were living through a kairos, a ‘time of urgent and providential election.’”

Merton said, “In the Negro Christian non-violent movement, under Martin Luther King, the kairos, ‘the providential time,’ met with a courageous and enlightened response. The non-violent Negro civil rights drive has been one of the most positive and successful expressions of Christian social action that has been seen anywhere in the 20th century. It is certainly the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States.”

Both Merton and King warned that failure to act on civil rights would be catastrophic for the United States. Merton said that if the country remained complacent, “the moment of grace will pass without effect. The merciful kairos of truth will turn into the dark hour of destruction and hate.”

This dark hour, or void, was often described by Merton as “The Unspeakable.” King knew of the Unspeakable as well. As he cautioned, “the Negro may be God’s appeal to the age—an age drifting rapidly toward its doom.”

Merton affirmed this statement. As he wrote in his essay “The Black Revolution: Letters to a White Liberal,” which was published in tract form by the Southern Christian Leadership Council, who saw Merton as an important ally, “The white and the Negro mutually complete one another. The white man needs the Negro—and needs to know that he needs him.”

Struggle for freedom is a struggle for Christians

Merton was adamant that King was acting as a true Christian should. He wrote in “The Black Revolution” that “Christianity is involved in the Negro struggle. Dr. Martin Luther King has appealed to strictly Christian motives. He has based his non-violence on his belief that love can smite men, even enemies, in truth. That is to say he has clearly spelled out the struggle for freedom not as a struggle for the Negro alone, but also for the white man.”

King’s pure nonviolent approach especially appealed to Merton, who had grown suspicious of the radical pacifism practiced by Father Daniel Berrigan and others, some of whom went so far as to condone suicide and violence as legitimate acts of civil disobedience.

There were other important connections between Merton and King: interest in the early Christian mystics, a condemnation of consumerism and materialism, an insistence upon the community of all people, and an overwhelming belief in the power of agape love.

Though it is difficult to locate explicit correspondence between King and Merton, King certainly knew of Merton, and not solely through the Yungblut connection. In 1963, King had proposed a pilgrimage to Rome for an audience with Pope John XXIII. He had requested permission for Merton to attend. Merton’s abbot, Abbot James, replied for Merton that “we have read your letter very carefully and what you have to say about your proposed pilgrimage. It certainly is a very ambitious project. I am sure that if you have purity of intention, and do it all for the love of God, that He will reward you. Unfortunately, we are not in a position to take part in any active way in the active ministry. However, what we can do, what we certainly will do—and that is, pray that God will bless your work for peace—that your pilgrimage will touch the hearts of the rulers of government, especially those rulers who do not believe in God (at least they say they don’t). It is worthy to note that after the resurrection, when Jesus appeared to his disciples and friends, every time he had just one word, peace be to you—Pax.” King later had an audience with Pope Paul VI at the Vatican after King received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Of King’s death, Merton wrote in his journal that it was “a beast of the apocalypse that finally confirms all the apprehensions—the feeling that 1968 is a beast of a year.”

Merton had received a letter from June Yungblut shortly before King was killed. It reads like both premonition and prophecy: “Martin is going to Memphis today. … I hope that he will soon go to Gethsemani. … If Martin had taken a period there he might have had the wisdom in repose to stay out of Memphis in the first place. … If there is violence today, Memphis will be to King what Cuba was to Kennedy. … Memphis is to be Martin’s Jerusalem.”

The music of Merton’s ‘Freedom Songs’

There is one further connection, one that is linked also to Merton’s and King’s mutual sorrow for John F. Kennedy’s death. Merton had written a series of poems which he titled “The Freedom Songs.” Originally, the poems were meant to be set to music and sung at a tribute concert for Kennedy in 1964. The poems were indeed set to music, but remained unused. Though Merton offered the poems to Coretta Scott King for King’s funeral in Atlanta, the songs were ultimately sung by the Ebenezer Baptist Church choir in a special tribute to King at the National Liturgical Conference in Washington later that year.

Following Merton’s own death, Mrs. King sent a telegram to the Abbey of Gethsemani: “I was deeply shocked and saddened by the news of our friend and staunch supporter, Thomas Merton. He was deeply committed to the ideals to which my husband dedicated his life and used his skills and talents to hasten the day when men will live in the blessed community of brotherhood. Dr. (sic) Merton’s poetic tribute to my late husband’s death has since been set to music and recorded by the choir of Ebenezer Baptist Church and may become a classic, as well as some of his other writings. The King family held Dr. Merton in the highest esteem. May the members of the family of Dr. Merton find comfort in the realization that the spiritual bond of love which unites a family is like a permeating glow, a steady flame which makes it possible for us to accept physical separation as fleeting and temporal because we know that the undergirding spiritual bond was deep and eternal.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.