Merton’s shining ‘epiphanies’ of light and insight

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published September 18, 2014

It is a passage that every Thomas Merton reader knows, and one beloved as well by people who have never even read Merton.

It adorns offices—even mine—nightstands, mantels, bookshelves, desktops.

It is usually framed, to demonstrate its importance.

It has become as familiar as Max Ehrmann’s “Desiderata,” in whose company it is often found.

It is the famous “Fourth and Walnut Epiphany” of Thomas Merton, usually abbreviated as follows:

“In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness. … This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud. … I have the immense joy of being man, a member of a race in which God Himself became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now I realize what we all are. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

Merton had this epiphany on the 18th of March in 1958. The following day, he wrote about the experience in his journal. By the time his great book “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander” was published in 1966, Merton had revised his initial journal entry into the more poetic version we know today.

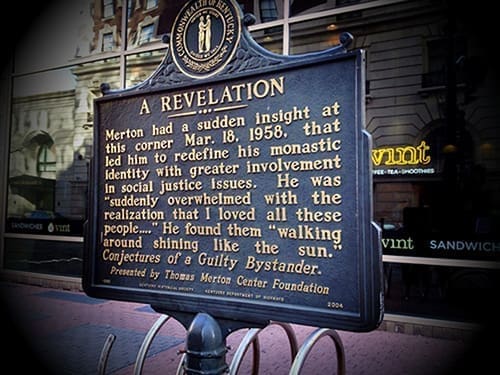

The passage became so famous that the city of Louisville erected a historical plaque in 2008 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Merton’s revelation. The area was re-named Thomas Merton Square. Though Merton himself would cringe at the thought of becoming a tourist attraction, the ecumenist and rebel in him would probably also be pleased to know that Walnut Street has since been named Muhammad Ali Boulevard, after another of Louisville’s most famous citizens.

A Catholic priest, Father Clyde Crews, has even published a book, “Crossings,” that examines the significance of the intersection of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville history.

Plaque in Louisville, Kentucky, where Thomas Merton had his “Fourth and Walnut Epiphany.” Photo by Kim Manley Ort (www.kimmanleyort.com)

What happened to Thomas Merton at the corner of Fourth and Walnut was a big deal; in fact, many Merton scholars mark it as a turning point in Merton’s monastic vocation.

That is probably not an overstatement. In 1958, Merton had been in the Monastery of Our Lady of Gethsemane, located just outside of Louisville, for 17 years. He had during that time professed his solemn vows in 1947 and been ordained a priest in 1949. He had also become one of the most beloved Catholic writers of the modern age, and was well on his way to securing his reputation as one of the most important spiritual writers of the 20th century.

Merton himself was, in fact, a big deal.

And he was troubled by his fame. He essentially renounced his masterful autobiography, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” saying of it that “unfortunately the book was a best-seller and has become a kind of edifying legend or something. That is a dreadful fate. It is a youthful book, too simple, too crude. I’m doing my best to live it down. I rebel against it, and maintain my basic human right not to be turned into a Catholic myth for children in parochial schools!”

Has that in fact happened also with the Fourth and Walnut epiphany?

A Google search of Merton’s Fourth and Walnut epiphany reveals an absolute trove of blogs and postings related to the passage. It seems as though every blogger with even the slimmest or most puzzling spiritual sensibilities has read the passage and adores it, and some brilliant religious thinkers have written beautiful tributes to it.

I think that’s fine. I adore the passage too.

I’ve read it aloud in classrooms, both secular and Catholic, and have literally seen it bring people to tears.

It is a beautiful insight into some profound truths. In one of my favorite passages (the entire description of the epiphany actually covers over two pages in “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander”) Merton “laughs out loud” with joy that “it is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many terrible mistakes: yet, with all that, God Himself gloried in becoming a member of the human race. A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweepstake.”

It is a beautiful insight into some profound truths. In one of my favorite passages (the entire description of the epiphany actually covers over two pages in “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander”) Merton “laughs out loud” with joy that “it is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many terrible mistakes: yet, with all that, God Himself gloried in becoming a member of the human race. A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweepstake.”

What many people miss, in merely reading an abridgement of the passage on a framed poster or desk ornament, is that Merton does not conclude with the beautiful image that we “are all walking around shining like the sun.”

Instead, Merton goes on to penetrate deeply into the essence of what it means to be human. The more he dwells upon our nature, the more he realizes that truly seeing the beauty in creation is something that “cannot be seen, only believed and ‘understood’ by a peculiar gift.”

What Merton’s epiphany finally reveals is that at the core of our being is “a point of pure truth,” and he describes this point, with typical Merton delight in paradox, as a “little point of nothingness and of absolute poverty (that) is the pure glory of God in us.”

This point, Merton says, “is in everybody, and if we could see it we would see these billions of points of light coming together in the face and blaze of a sun that would make all the darkness and cruelty of life vanish completely.”

That, too, is beautiful. Yet as Merton concludes, there is “no program for this seeing. It is only given.”

No, you can’t tell people they are all shining like the sun, though of course we’re told that all the time, by people as diverse as C.S. Lewis, The Beatles, and President George H.W. Bush!

To fully understand the complexities of Merton’s epiphany, one has to place the Fourth and Walnut passage in the context of “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander,” which is both a Merton masterpiece and a difficult book about a deeply troubled world. In the book, Merton asks questions about race, war, a culture of death, religious separatism, a hesitant ecumenism, and consumerism, and concludes that most of our problems are the result of a light very different from a “pure diamond, blazing with the invisible light of heaven” or the “shining sun.”

In a passage not nearly as well known as the Fourth and Walnut epiphany, Merton writes about his deepening appreciation of “the beauty and the solemnity of the ‘way’ up through the woods” that surround his hermitage. The sun is here, too, a “kingly sun … distinguished as a person and he shone silently and with solemn power through the branches, and the whole world was silent and calm.”

Of course, Merton is a fine enough writer to know that his little piece of ground in the woods of Kentucky is not the whole world. Yet he is also gifted enough to realize that in a sense it is.

He concludes, “It is essential to experience all the times and moods of one good place. No one will ever be able to say how essential, how truly part of a genuine life this is: but all this is lost in the abstract, formal routine of exercises under an official fluorescent light.”

It’s quite a contrast: the dazzling sun of God’s love and the increasing institutional dehumanization we confront in our offices, or with shiny new “smart” phones, or with video-on-demand, or with wars waged by remote control.

Merton is right. To see the essential beauty of ourselves in the glory of God and his creation is a gift.

But his second epiphany of light offers an equally important lesson.

The trick is to be dazzled by the one, and not blinded by the other.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.