A real life fairy tale: ‘Brother Joseph and the Ave Maria Grotto’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published November 22, 2013

Had I asked my Southern literature and culture students twenty years ago the question I asked them last week, I would have gotten a very different answer.

Had I asked my Southern literature and culture students twenty years ago the question I asked them last week, I would have gotten a very different answer.

What did they know about Southern folk art? Not much, it turns out.

You mean, I said, you’ve never heard of Howard Finster and Paradise Gardens in Summerville, Georgia? You’ve never heard of the Reverend John D. Ruth’s Bible Garden near Philomath, Georgia? You’ve never even heard of R.A. Miller’s whirligig field in Gainesville, Georgia?

Blank stares. Shaking heads. Fingers back to iPods.

It’s not the students’ fault. Finster, Ruth, and Miller, and many others like them throughout the Deep South, are all dead, and those who should have preserved their achievements have not always been good stewards of the legacies.

And the South is changing, as it always is, and the wonderful and mysterious tradition of the primitive artist may be fading too.

Whether we refer to them as primitive artists, folk artists, or—most accurately—visionary artists, the legacy of the outsider self-taught artist is in jeopardy in the South.

But not in Cullman, Alabama. There, at St. Bernard’s Abbey, a Benedictine monastery, the most unique and perhaps most astonishing work of Southern visionary art is still seen by over 60,000 people and pilgrims a year. The Ave Maria Grotto, conceived and built by Brother Joseph Zoettl, is one of the most startling folk installations in the South. And when we consider the man who created it, it becomes even more amazing.

Brother Joseph wasn’t an African-American tenant farmer. He wasn’t an evangelical preacher. He wasn’t a shade-tree mechanic. He wasn’t any of the things we usually associate with Southern visionary art.

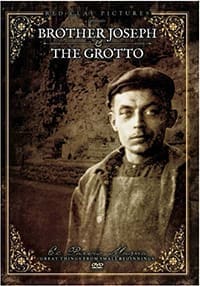

Brother Joseph was a monk—a German, Catholic monk. And he was little. And he was a hunchback. But he was a brilliant and gifted artist, and his creation endures in Cullman, where surely more visitors will come after they see the recent film by Cliff Vaughn, “Brother Joseph and the Grotto,” that presents a wonderful overview of Brother Joseph’s life and work.

Vaughn presents a compelling presentation of the artist’s life, a life the filmmaker frames around the Latin proverb Ex Parvis Magna: Great things come from small beginnings.

Michael Zoettl was born in Bavaria in 1878, and as Vaughn’s film reminds us, his life unfolded like a Germanic fairy tale. His mother died when he was young, and he was raised by his father and an archetypal wicked stepmother. He escaped death numerous times, both as a boy and later as a man. He almost drowned. He almost burned to death. He was injured, permanently, in an accident that left him a hunchback.

Zoettl arrived in America, at Ellis Island, in 1892. He immediately went to St. Bernard’s Abbey in Cullman, about as far from Bavaria and Catholicism as you can go. He entered school at the abbey, learned English, and intended to become a priest. Zoettl worked hard, and fully embraced the Benedictine creed of Ora et Labora: Prayer and Work. While working in the belfry of the abbey church, which the monks were building themselves, Zoettl was severely injured in an accident that aggravated an existing back condition and left him a hunchback. Worse, the accident impeded his schooling and prevented him from becoming a priest, due to his “canonical impediment.” Eventually, Zoettl decided to remain at the monastery as a lay brother, and he later formally joined the community as Brother Joseph. Except for brief trips to Virginia, which he hated, and Tuscumbia, Alabama, where he might have crossed paths with W.C. Handy and Helen Keller, Brother Joseph spent the rest of his life at St. Bernard’s, working primarily as the coal man in the abbey’s powerhouse. That’s how he might have spent the rest of his life, for as the film reminds us in a refrain, “it wasn’t his time.”

A series of coincidences, or perhaps divine intervention, changed the course of Brother Joseph’s life. In the monastery library, Brother Joseph discovered St. Therese’s book about her “Little Way”; as the film suggests, Zoettl’s constant reading of the book led to a creative impulse, as he began building miniature models of churches. A fellow monk had received five hundred statues of the Virgin Mary, and Brother Joseph made little grottoes for two of them. They sold quickly at the monastery store. Brother Joseph made grottoes for the other 498; they sold too. Eventually, Brother Joseph developed what he called a “hobby” and sold thousands of his little grottoes that went all over the world.

Brother Joseph began making more miniatures, which he placed on display on the monastery grounds. When tourists began coming, Brother Joseph hoped to move his creations to an old stone quarry on the monastery property, but the abbot said no. About 12 years later, in the spirit of the Benedictine Rule’s wisdom of the impossible task, the decision was reversed and Brother Joseph was given the space at the quarry. At about the same time, in 1933, a train wreck left a load of damaged Alabama marble that Brother Joseph was given to use for his ongoing project.

Like most outsider artists, Brother Joseph depended upon found objects as the media for his creations. As a speaker in the film puts it, “other people’s trash was his treasure.” Out of this trash—including railroad spikes, chicken wire and broken china—he sculpted remarkably detailed miniatures of historic religious and classical buildings. He modeled the famous structures of Jerusalem and Rome, and places that evoked his own childhood memories and Bavarian culture.

The Ave Maria Grotto, the official name for Brother Joseph’s creation, cannot really be appreciated except in person, and this is where Vaughn’s film becomes most helpful, even for those unable to visit the Grotto. The film is packed with wonderful photographic stills and evocative dramatizations, which reveal the detail and scope of decades of meticulous work.

Vaughn structures his film, purposely, as a fairy tale. As Vaughn has explained, Zoettl’s life includes so many of the archetypal elements of the great Germanic fairy tales that it is almost impossible to describe Brother Joseph in purely literal terms. The stepmother, the escapes from death, the physical deformity and the ultimate redemption from all these near catastrophic experiences created a human being who became almost an iconic hero.

The film is narrated, for example, by a disarmingly simple storyteller, played by Norma Baker Gabhart. At first, her narration seems a distraction, but then the point becomes clear: Vaughn really is telling a fairy story, almost beyond belief, and Gabhart’s story-telling then becomes reassuring, then authoritative. It is the perfect voice for the film. Vaughn even frames the images of Gabhart in a manner similar to the odd style Charles Laughton used for Lillian Gish in his masterpiece “The Night of the Hunter.”

Yet there are also elements of Brother Joseph’s life and art that are far removed from fairy tales and are strikingly relevant to the latter half of the 20th century. Brother Joseph was a keen follower of contemporary events, and among the most moving exhibits in the Grotto are memorials to Alabama soldiers killed in World War II and the victims of the atomic bombings in Japan. Just as moving is the effect the Grotto had as Alabama and the rest of the South tried to move away from segregation. For years prior to the events of the Civil Rights era, the primary visitors to the Grotto were Midwestern Catholic tourists on their way to the Gulf Coast and curious travelers who looked at the Grotto as a kind of roadside attraction.

Yet in the Civil Rights era, the monks used the Grotto as a gathering place in which all were welcome, including African-Americans who were especially reminded that one of the Magi was probably an Ethiopian. Vaughn incorporates archival footage from the period which demonstrates that the Grotto had indeed become a place not for curiosity-seekers, but for those who desired prayer, peace and communion with their fellow man.

Throughout the creation of the Grotto, Brother Joseph wanted no attention, no celebrity. He remained shy and humble. Only one archival film of him actually working in the Grotto survives, a Paramount newsreel of “Unusual Occupations” that does not understand the spiritual aims of his art.

Brother Joseph was 80 years old when he built his last miniature, a model of the Basilica at Lourdes. He died at the age of 83 in 1961.

So many Southern folk art installations have disappeared or are deteriorating. That the Ave Maria Grotto endures and thrives is a testament to its spiritual value. And Cliff Vaughn’s film, now available to purchase online from Red Clay Pictures, is a great gift to ensure that Brother Joseph’s little creations continue to inspire great things.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.