The Gen-Z stare and contemplative prayer: Learning to see in silence

By DR. DAVID KING, Ph.D. | Published September 24, 2025

Of the universal divide between generations, maybe the great British rock band The Who put it best in their song “The Seeker”: “You’re looking at me; I’m looking at you. We’re looking at each other and we don’t know what to do.”

If you have any relationships with members of Generation Z—the children born between 1997-2012—you know “The Stare.”

To the uninitiated, it may first appear an ambivalent, ambiguous, blank look that emits no emotion, no interest, no reaction. I live with two members of Generation Z. I teach about 100 of these young people every week, at both the university and the parish. I know that stare. It reminds me of long car trips I took as a child, looking out the window for hours, at the interstate highway landscape of Southeast Georgia.

The mainstream media wants us to believe that the Gen Z Stare is defiant, afraid and inhospitable. I am trying to think differently. I think, like The Who, that the gaze is searching and seeking. It wants affirmation. And it is only a stare. I’d rather be looked at than sneered at, which is what my generation so often did.

In “Thoughts in Solitude,” his beautiful 1956 book of meditations upon spiritual life, Thomas Merton grapples with the merger between contemplation and action required of the monastic vocation. Contemplation must precede action; as Aesop reminds us, before we leap, we should look. And often, the most meaningful contemplation comes when we are silent and alone. In his frank admission about the complexity of living the paradox of silent action, Merton wrote what became one of the most beloved prayers in 20th century ecumenical Christianity:

“My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore I will trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

It strikes me that Merton wrote this meditation when he was working with young people himself as their Master of Students at his monastery in Kentucky. I have listened to hours of Merton’s teaching, and I can attest that he often grew frustrated with his students’ lack of preparation and reluctance to read. Merton confronted this universal schoolroom apathy with humor, passion and persistence. Sometimes, following the adage that when the student is ready the teacher will appear, he did nothing.

If we think for even a moment about what high school and college students have experienced over the past several years, it is easier to understand why they “have no idea where they are going.” A young person who is confronted daily with global pandemic, horrifying school shootings, and the threat of world war has every right to feel lost and unable to see. Anxiety and isolation can certainly muddle our perception, and the cacophony of social media makes it difficult to discern and make choices.

Yet students now, as always, do have desire. What they must strive to attain is faith. Merton makes a great leap: “I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it.” With that faith, Merton sees his loss, his blindness as only temporary, a state of “seeming” rather than being fixed. From that perspective, Merton concludes rightly that “You will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

Looking and seeing

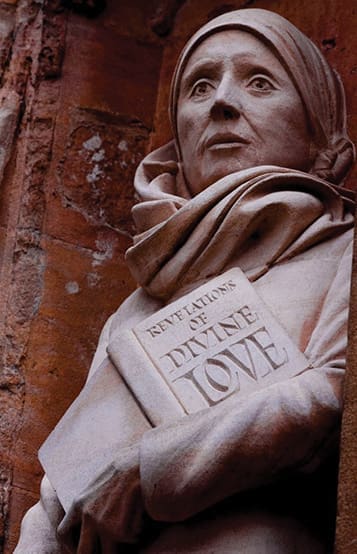

Dame Julian of Norwich, the great medieval English anchorite and mystic, was given 16 “showings” in 1373. In her account of these visions in “The Revelation of Divine Love,” she implores her reader to see. “Intently, wisely, and meekly, look at God.” Julian urges her reader not to look at the superficial, but to look within.

Dame Julian of Norwich, the great medieval English anchorite and mystic, implored others not to look at the superficial, but to look within. Photo by David Holgate FSDC

Almost all the great mystics in the long Catholic intellectual, philosophical, and aesthetic tradition are concerned with looking and with seeing. Perhaps what we deride as the Gen-Z “stare” may in fact be an entry point into the more profound concept of gaze.

Recalling his famous epiphany at the intersection of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, Merton writes that “I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depth of their hearts, … the person that each one is in God’s eyes. If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time.” Concluding that only with placing complete trust in God, Merton argues that “The light of heaven is in everybody, and if we could see it we would see these billions of points of light coming together in the face and blaze of a sun that would make all the darkness and cruelty of life vanish completely.”

Merton had another profound epiphany at Polonnaruwa in Sri Lanka in 1968. On his Asian Pilgrimage, mere weeks before his sudden death, Merton went to visit the four massive Buddhist statues that are carved within the cliffs at Gal Vihara. Merton wrote in his Asian Journal that he was profoundly moved by his encounter with the massive religious statues. “Looking at these figures, I was suddenly, almost forcibly, jerked clean out of the habitual, half-tied vision of things.”

Merton describes “The silence of the extraordinary faces. The great smiles. Huge and yet subtle. Filled with every possibility, questioning nothing, knowing everything, rejecting nothing, the peace not out of emotional resignation but of one that has seen through every question without trying to discredit anyone or anything without refutation.” Merton acknowledges that for “the mind that needs well-established positions, such peace, such silence, can be frightening.”

Merton might very well be describing one of my morning classes, still and silent as I enter the room, but coming to life if I do my job well. Part of that job is empathy. I think that I have succeeded as a teacher for so long because I have always tried to remember that I was once a student too.

Relearning how to think

Flannery O’Connor’s teacher at Iowa, Paul Engle, recounted that O’Connor never spoke, but that the chair she sat in glowed. St. Thomas Aquinas’ fellow students called him “the dumb ox.” And I have always liked what Charlie Brown says of Pigpen in the Peanuts Christmas special: “Don’t think of it as dust. Think of it as maybe the soil of some great past civilization. Maybe the soil of ancient Babylon. It staggers the imagination. He may be carrying soil that was trod upon by Solomon, or even Nebuchadnezzar.”

“Sort of makes you want to treat me with more respect, doesn’t it,” replies Pigpen.

We too often now resort to easy generalizations and oversimplification regarding almost every subject. From memes to reels, from tweets to texts, in the AI age we must relearn how to think.

The Gen-Z stare, from my experience in working with these students as both parent and teacher, belies a depth of understanding and emotional intelligence far greater than we might think upon cursory consideration. And as Muriel Spark’s Miss Jean Brodie knew, we can try to “put in” all we want, but the students won’t learn anything until we “draw out” what has been there all the while.

The seeker, the mystic, the contemplative and the saint are all after the same thing, the ideal that Plato speaks of in “The Allegory of the Cave.” They want not only to look, but to see, and in seeing come to understand both God and ourselves as we really are.

One of my mentors and godfathers, Professor Bill Sessions, once told me about a visit he made to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, late in the afternoon, years before the massive expansion of the building. It was about half an hour before closing, and he had come to look at the visiting installation of some of Monet’s “Waterlilies” canvases.

The painting was so massive that Bill didn’t know how to approach it, particularly with limited time. It was big, and abstract, and even a bit frustrating. Then Bill understood. “I decided,” he said, “that rather than looking at the painting, I would let the painting look at me.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of OCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.