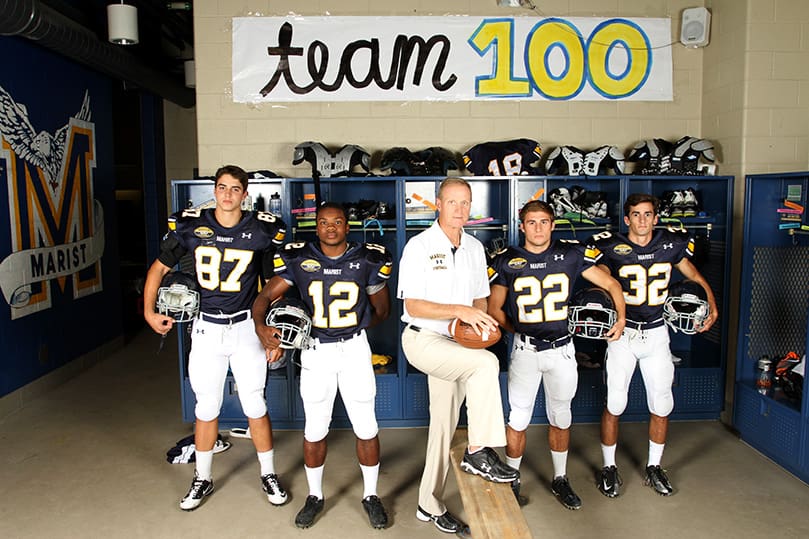

Alan Chadwick, center, the head varsity football coach at Marist School, Atlanta, is joined by four seniors from the 2012 team. They include (l-r) tight end and defensive end Greg Taboada, quarterback and defensive back Myles Willis, running back and defensive back Gray King and free safety Brandon Young. Chadwick reached and surpassed his 300th career victory mark earlier this season. Photo By Michael Alexander

Atlanta

‘War Eagles’ Follow In Footsteps Of Marist ‘Cadets’

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published November 8, 2012

Charles Saye would strap on a leather helmet and come off the sidelines to take his place on the Marist line. Without face masks and wearing simple pads, the scrappy team faced off against larger teams.

“We were like a band of brothers, in other words. We stopped a lot of big, strong teams,” said Saye, a World War II veteran and at 92 one of the oldest alumni of Marist football.

“Most of the men on the line were bloody,” he said.

Marist football was born on a spit of clay where commuters in downtown Atlanta now park their cars and minivans before heading to work in the nearby office buildings towering over the parking lot. Games were played at Ponce de Leon Park, a baseball stadium.

Sitting in the stands, 92-year-old Marist football alum Charles Saye, left, watches Marist defeat Therrell High School 53-0 during the fourth game of the 2012 season. Saye, a wide receiver and defensive end, played during the 1939 season and the first game of the 1940 season before he was called up to serve the country in the Army during World War II. Photo By Michael Alexander

Today, the players scramble toward the end zone on synthetic turf. More than 4,000 screaming fans fill the bleachers at the home field, Hughes Spalding Stadium. They dress out in War Eagles blue.

Students at the private independent Catholic school in Atlanta have played a century of football. It is one of the oldest high school programs in Georgia with one of the top coaches. Some 235 students participate in the football program.

“Tradition is so important to a school. Having 100 years of football is incredible,” said Tommy Marshall, the school’s athletic director.

The Marist Cadets, as the early team was known, struggled. Sports historian Richard Reynolds found the first recorded games were losses. In 1922, the team had its first undefeated season.

The team now makes a perennial appearance in the playoffs and has earned two state championships. This year, the team uniforms have a patch for the centennial, a special emblem is on the field and the school invited former players, cheerleaders and coaches to parade into the stadium in front of a home crowd.

“It’s a great source of pride for everyone involved in the program,” said varsity football coach Alan Chadwick about the anniversary, and it helped fuel the team’s successful season. “Hopefully, it brings back a lot of fond memories.”

Chadwick also earned his 300th career win this season, putting him in rare company among Georgia high school football coaches. He has led the War Eagles since 1985, and his team took home the state championship trophy in 1989 and 2003. This season the team is on a seven-game winning streak with one loss.

Leaders see the football program as part of the school’s mission to “form young people in the image of Christ.”

Marist Father John Harhager, the school president, said the football field can be another type of classroom.

“Students who participate in athletics learn important life lessons about teamwork, leadership, discipline and the value of hard work. In this way the football program and other extracurricular activities are an extension of the classroom,” he said.

“The centennial of our football program reminds us of our connection to the long history of the school, and it helps build a strong sense of community. Football at Marist, like all our other athletic teams, is an integral part of our mission to help form young people in the image of Christ,” he said.

Football at the school goes back to 1903, according to historian Reynolds, a Marist graduate and a retired Atlanta attorney. He traced the origins of the game when an uncoached team of boys took on the Peacock School.

“They got clobbered,” he said, 58-0.

Football alum mark the tradition of the “Long Blue Line” and 100 years of football at Marist School, Atlanta, as they walk from the Centennial Center to the field in between the line of current players, prior to the Sept. 21 game against Therrell High School. Photo By Michael Alexander

The athletic fields were behind the three-story schoolhouse that stood on Ivy Street, now called Peachtree Center Avenue, opposite Sacred Heart Basilica. The early football program faced opposition on the field and in the school. Reynolds said the school’s principal, then called the “prefect of studies,” opposed the idea.

It was a new game when the top sports of the day were baseball, horse racing and boxing, he said. “Football was just beginning. It had a big way to go before it was dominating,” said Reynolds.

He scoured the archives in the Atlanta History Center, Emory University and the public library of the big Atlanta newspapers at the time to put together a yearly history of the program.

The centennial honors 100 cumulative years of Marist football. It starts with single years in 1903 and 1912, followed by uninterrupted seasons from 1914 to the present, with the exception of 1952 when the sport was dropped.

Nearly 300 former players, cheerleaders, coaches and managers returned to the school for the special celebration in September.

Saye, who grew up in southwest Atlanta, attended Marist and played a season in 1939 and one game in 1940 before his National Guard unit was mobilized.

Saye was an end, on both the offensive and defensive sides.

“We played both ways in those days. We didn’t have a two-platoon system,” he said. He wasn’t a starter but would come in as a substitute.

The team played against the big teams, he recalled. One game was against Albany High School, a powerhouse. Saye said Marist couldn’t catch a break, with referees calling back touchdowns.

The Albany team “scored with the help of the officials” and won the game, he said.

Sports historian Reynolds attended the 1948 state championship game. It was against Macon’s Lanier High School at the then new Grady Stadium, at the corner of 10th and Monroe streets in Atlanta. After the clock ran out, it was a tie at 13 apiece.

Marist linemen Tommy O’Haren, left, and Stephen Weltlich join hands for the praying of the Our Father during a pre-game Mass in the school’s Centennial Center, Sept. 21. Photo By Michael Alexander

Marist fans hung their heads when officials announced the Macon team earned the championship. The game was decided on the penetration rule, which awards the game based on the team that penetrates the deepest toward the opponent’s goal line.

“It was the single most disappointing moment in Marist High School history,” he said.

The football program generates enthusiasm on campus and builds “espirit de corps” among the players, fans, students and community, Reynolds said.

A funny story is the time in 1932 when a Decatur coach called off the game because of weather. The Marist coach disagreed, so he took the team out to the Atlanta suburb anyway. The Marist players lined up and kicked off. With no opposing team to return the ball, the Marist coach declared a forfeit and claimed victory.

Coach Chadwick said a goal for his program is to impart to the players the importance of sacrifice to be successful and “striving to be the best they can be.”

After football ends and players hang up their cleats, students should always remember the “lessons learned from working together for a common goal,” said Chadwick, who attended the University of Georgia on a football scholarship before transferring to East Tennessee State.

Earning the 300th win early in the season, he’s been adding to the record. But he said the milestone reminds him about the many players and coaches he has worked with that have made the football program a success.

At the start of the year, with the 300th win on the horizon and the 100-year celebration, players and coaches had a goal to work toward. The team reached an 8-1 record on Nov. 2 after they bested an undefeated Chamblee High School, 24-0.

“(The milestones) gave the kids a sense of urgency for working and preparing for the season,” he said.