Mystery, mistakes and miracles: practicing golf and Catholicism

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published July 25, 2024

All my life, I’ve been fascinated by golf. I don’t claim to be good at it, mind you, but enamored I remain.

I grew up with people who both adored golf and loathed it. My father claimed it wasted an entire weekend. My grandfather played nearly every day, most often at Bobby Jones Golf Course in Atlanta, where his nephew Ronald caddied and did other odd jobs. My grandfather once said of Ronald, “The boy may be stupid, but he can flat out hit a golf ball.” I’m still working out how my grandfather valued a golf swing over intelligence, but like so much in golf, it remains a mystery.

I started playing golf in the yard with a baseball bat and a range ball. I moved up to my grandfather’s 9-iron and plastic practice balls. When I was old enough—that’s about 8 for a Gen X-er like me—I spent entire summer days at a nearby golf course, hiding in the woods until a hole cleared so that my friends and I could quickly play. When we weren’t illegally hacking in the fairway, we were dashing out of the trees to swipe golfers’ errant shots. I see now that so much of my early golfing days were linked to a deepening awareness of sin.

I cobbled together a pitiful set of clubs from yard sales and thrift stores. By age 16, I had still never been able to play a proper round of golf. The summer that I could first drive a car, I went with three other neighborhood boys to the old Par 56 golf center on Cobb Parkway, what was then known as “the four-lane,” and sauntered into the pro shop. Clubs fell out of a hole in the side of my canvas bag and clattered to the floor. “Oh, no—no, no, no,” said the man at the counter. “This ain’t no Mickey Mouse club. Y’all get out of here.” I think Par 56 is an industrial center now.

One of my favorite golfers of all time, Lee Trevino, once gave a clinic at Par 56. Trevino, a Mexican American Catholic, has always been a hero to certain kinds of golfers like me, people not born into country club families, but those of us who learned on near-dirt fairways and rickety driving ranges, and even hiding in forests in the deep rough. He learned to play golf as a caddie, and he served in the Marines. He became famous for his fade shot that distinguished himself as an original and daring player.

Trevino, who cultivated a public personality and answered to nicknames such as “Super-Mex” and “Merry-Mex” won the U.S. Open and PGA Championship two times each and completed back-to-back wins at the British Open in 1971 and 1972. A fan-favorite, he once joked “If you are caught on a golf course during a storm and are afraid of lightning, hold up a 1-iron. Not even God can hit a 1-iron.” Not long after, Trevino was struck by lightning on the golf course. Though he described the experience as strangely peaceful, he struggled mightily to remain awake so that he would live. “I deserved it,” he said. “God can hit a 1-iron.”

Though Trevino has often said that “I keep most of my thoughts to myself,” he does acknowledge that he practices his religious faith. A few statements he has made reveal a simple wisdom, much like his approach to golf. “When you really deep down look at it,” he has said, “we go to bed every night, get up every morning, stay here for 70 or 80 years, and then we die.” It reminds me of what the great baseball announcer Vin Scully, also a Catholic, once said about players who are on the day-to-day list: “Aren’t we all.”

Trevino has frequently worked with the St. Jude organization. He has recalled how difficult it was for him to see and work with innocent sick children. He finally made peace with childhood suffering by realizing that “The Lord doesn’t just want old people. You know, he wants some young people, too, and good people. He takes care of them. He takes care of them.”

Trevino has spent most of his senior years teaching, which has been an absolute passion for him, and he continues to model a folksy approach to life that belies his deep insights.

An Act of Love

There aren’t many Catholics who have achieved the success that Trevino did, though a look at the current game reveals three stellar golfers who are also practicing Catholics. Jordan Spieth has won the Masters and both the U.S. and British Opens. Scottie Scheffler is a two-time Masters winner. Rory McIlroy has won the U.S. and British Opens as well as the PGA Championship.

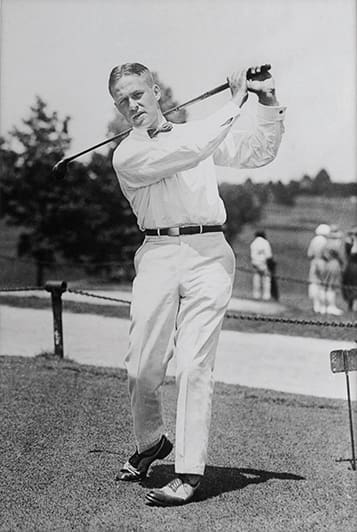

Golfer Bobby Jones is photographed in 1921. He reported converted to Catholicism three days before his death as an act of love for his wife, Mary. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Many readers may not know that one of the greatest golfers of all time became a Catholic. Bobby Jones—the colossus from Atlanta who won the Grand Slam, created the Masters, and achieved so many triumphs in sport, life, and letters—converted to Catholicism three days before his death in December of 1971. He converted as an “Act of Love” for his devout Catholic wife of 47 years, Mary Malone. I told my son Nick, who is learning to play golf, what Jones did. He deadpanned, much like Trevino might, “Or maybe he was scared.”

Jones was Baptized and received the sacraments on his deathbed by Msgr. John D. Stapleton, who was rector of the Cathedral of Christ the King in Atlanta.

I don’t think Jones was scared. I think Jones, who was a Christian, had learned so much about the mystery of suffering through his terrible illness and paralysis that he must have been called into the fullness of the Catholic faith.

Consider this remarkable story about Jones, taken from the memoirs of Bishop John O. Barres, who had served as a caddie in the early 1970s at Winged Foot, New York where Bobby Jones won the 1929 U.S. Open. Bishop Barres supports his account with reporting by Dick Schapp.

Jones made a long putt to force the tournament into a playoff. USGA officials determined that the 36-hole playoff round would begin the following morning, Sunday, at 9 a.m. Jones requested that the playoff not begin until at least 10 a.m. so that his opponent, Al Espinosa, could attend Mass. The request was granted. Bobby Jones attended the Mass at St. Vito’s Church along with Espinosa.

Jones then went on to beat Espinosa in the playoff by an astounding 23 strokes. The next year, he won the U.S. Open again; completed his Pro-Am Grand Slam, and retired from competition.

Bishop Barres puts the story in proper context: “What an extraordinary story of what it means to be a Christian gentleman. … I like to think that Bobby Jones’ generous, magnanimous and ecumenically thoughtful and considerate Eucharistic gesture at the 1929 U.S. Open at Winged Foot helped prepare and open his soul to embrace our beautiful Catholic faith and the grace of receiving Our Lord in the Eucharist three days before he died.”

The heart of the game

The great writer and editor George Plimpton once proposed a “Small Ball” theory of sports literature. Plimpton argued that the smaller the ball, the better the literature. Granted, baseball literature is fantastic. And fishing, which doesn’t even have a ball, has produced some of the finest sport writing in English. The canon of golf writing is almost absurd. If golf writing isn’t our best sports literature, it certainly is its most Zen.

The other day I took Nick to the driving range. He wanted to hit 50 balls. That became 100, then 150. I sat behind him on a bench, where on either side of him I watched two men about my age also hit golf balls. One hooked badly to the left, the other sliced to the right, each towering drive reaching an apex before being snatched away as if by invisible fingers. Between them, Nick hit long and straight and high. It was beautiful and sad at once, this ebb and flow of life on artificial tees.

I hope my son continues to practice his game, and that golf becomes a source of joy and mystery—and even instructive suffering—that it has been for me. But I also hope that like Trevino and Jones, he finds at the heart of the game love, not just love of the sport, but love of what it can teach us about fundamental values. Trevino found more joy in golf by teaching others. Jones had the insight to know when it was time to stop. And each man had an epiphany, whether by light or lightning, that he never expected. As golfers often say after one great shot in a bad round: and that’s why we keep coming back.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of OCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.