Conyers

Trappist priest remembered for forming deep connections with others

By GRETCHEN KEISER, Special to the Bulletin | Published September 5, 2019

CONYERS—Abbot Augustine Myslinski, speaking at the Mass of Christian Burial for Father James Behrens, OCSO, looked out Aug. 21 at the over 500 people who had come when 200 were expected.

Exactly where he was standing, the abbot said, Father James had given over the years “many beautiful homilies” about people both living and deceased. He had a remarkable gift for observing people around him deeply and understanding the kindness and the pain in the person before him, the abbot said.

“Now it is time for James to hear a homily about him. In faith we believe that he is present to us here. He is listening.”

Father James died on the feast of the Assumption, Aug. 15, in a hospital after experiencing complications following a lung biopsy. He was 71 and a monk for 25 years and priest for 45 years.

He entered the Cistercian order at the Monastery of Our Lady of the Holy Spirit in Conyers in 1994. Before that he served as a parish priest for 20 years, ordained in 1974 for the Newark Archdiocese in New Jersey.

While the abbot said he probably couldn’t give a definition of what makes up a typical monk, “One thing I can assure you of, Father James Stephen Behrens was not a typical monk.” Affectionate laughter rippled through the congregation in the abbey church.

Father James, born Jeff Behrens, grew up in New Jersey, one of seven children in a tight-knit Catholic family. By his senior year in high school he had decided on the priesthood and entered the seminary. He didn’t begin writing in public until he was in his 40s. As he detailed in one of his columns, he experienced a life-altering “grace” when Walker Percy invited the priest to his home after he bought over $150 worth of Percy’s books in the author’s hometown Louisiana bookstore.

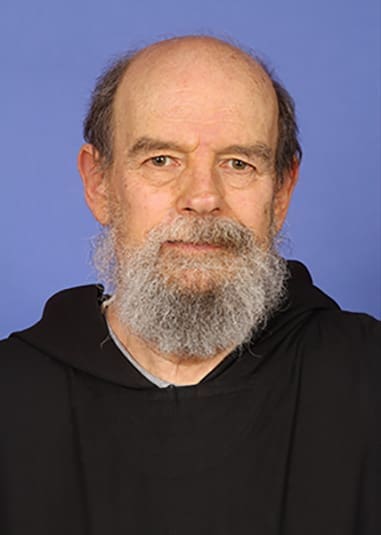

Father James Stephen Behrens, OCSO

Photo By Michael Alexander

Father James said Percy encouraged him to “write with hope about what I feel, and that is what I have always tried to do.” Grace was always in his book titles. He had completed all the work for a Ph.D. in literature, except the dissertation.

From 1989 until his death, Father James wrote prodigiously in spiritual reflections and columns, as well as personal letters, and made photographs to accompany his reflections or those of other authors. His computer holds tens of thousands of his photographs, the abbot said. Like his first column, “Andy’s Diner,” much of his writing drew on his experiences in everyday life with family and other real people in down-to-earth settings, while pointing to the presence of God’s grace in ordinary life.

His columns appeared in the Rockdale Citizen and The Georgia Bulletin, where he was regularly published for at least 12 years, to the National Catholic Reporter and Living Faith.

Sketching a memory of Father James walking through the cloister “slow and easy, his ragged blue jeans showing from underneath (the monastic habit), a bit disheveled,” the abbot said in jest that “he was to me the original slacker.” But he also seemed to carry a burden of sorrow.

He took James as his religious name in memory of his twin brother, Jimmy, who was killed in a car accident in high school.

“He seemed to always have to carry the weight of the tragic loss of his twin brother. … He bore that pain I think all his life, but that’s OK because sometimes serious creativity can be borne out of such pain and challenge,” the abbot said.

His contemplative spirit “was a little unconventional but a contemplative spirit nonetheless. James was drawn to this life here … the quiet, the space to be alone, to be more in touch with God and himself, giving expression to the many God-given talents he had, the gifts.”

One was writing an “astounding” number of letters. “I would venture to say he wrote the majority of the people in this space right here, and he did it consistently,” the abbot said, adding that he wrote the abbot’s mother every year on her birthday, which the abbot said he never did. “He connected with people. He did it so effectively in a very peaceful and quiet way.”

Men don’t enter the monastery because they are holy but because they desire to become holy, the abbot said. “Even though James, I don’t think, ever used the word holy, I think he desired it very much and lived it even in an unconventional type way. His faith was not always explicit, but it was always there in a very implicit, powerful way.”

Father James died on the feast that celebrates the reality of heaven, the feast of the Assumption. The abbot read from one of his past columns that said, “I hope there is a welcome area in Paradise. I like to think that Mom and Dad will be waiting for me when I arrive, for that flight will surely be on time. And I will cry with joy and hug them and kiss them, and ride across the waters of eternal life, into a year that lasts forever. I believe that will happen. It is the truth I knew here, the truth they gave me, in the best of times.”

New Jersey memories

His older sister, Mary Behrens McCarthy, said she believes that as the passage said, her brother really celebrated going home.

Growing up in a “nice compact little house” in Montclair, New Jersey, with their parents and grandmother, she and her six siblings felt “very privileged.” Coming up through Catholic grammar school and high school was part of it, putting down strong roots in a faith community and friendships that would be there for them in sorrow, even bringing several childhood friends from across the country to Conyers for Father James’ Mass and burial.

“For all of us we really appreciated our parents’ faith life and their love for each other and their love for us,” she said.

Their father was very grateful that Jeff had already decided to become a priest and was accepted to the seminary before his twin brother was killed, she said. “He knew what he wanted.”

“He went on to his life, his priesthood, acknowledging the loss, and I think it helped him to reach out and touch others too. My husband and I had five children. Our son was killed on a Boy Scout trip when he was 14. He understood our pain of loss at a deeper level.”

To his nieces and nephews he was “Monk-le Jeff” and very much a part of the extended large family of his siblings, while celebrating baptisms, marriages and funeral Masses.

“In the tapestry of everybody’s life, he was always there. To be honest I feel like he still is,” she said.

While he devoted several decades to ministry in the diocesan priesthood, she said her brother told her he did not have the business sense or inclination to become a pastor. And, she said, “I think he really missed community.”

He began to make retreats at the Conyers monastery after she and her husband moved to Atlanta. He visited several Trappist monasteries before entering in Conyers. He continued to write letters to families in his former New Jersey parishes where he had celebrated the sacraments and had been a youth minister. Hundreds of messages and old photos were posted on social media since his death.

“The Leaf on a Thread” is a photograph taken by Father James S. Behrens, who led photography retreats at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers.

Reading his columns, the sharp memories of his childhood, family, neighborhood and era in which he grew up were described in simple language but struck a deeper chord of God’s presence.

“I really felt that his creativity—whether it was through the lens of a camera or whether it was with music or writing a homily or writing a letter—and the way he kept in touch with hundreds of people, I honestly think all those things were the deepest expression of his faith and his journey to God,” his sister said. “All along the way he reached out to people.”

“A great friend”

Trappist Brother Mark Dohle remembers reading “Andy’s Diner” when it was published and thinking whoever wrote that “would really make a great friend.” Several years later Father James entered the monastery. When Brother Mark eventually realized this new entrant was the writer he admired and told him, Father James just looked at him and blinked a couple of times as if he couldn’t believe someone was saying that.

“We were good friends. He was like a brother to me,” Brother Mark said.

“He was a good monk and a good member of the community. When we had a community discussion about him (following his death), everybody spoke. Everybody appreciated him, his homilies,” he said.

His example inspired Brother Mark to write and share his writing online.

“He was extremely accepting of other people. He was a kind person. … Anybody could talk to him about any struggles and he understood. He never judged. He wasn’t a gossip. You felt safe with him.”

Through his writing he made deep connections with readers, Brother Mark said.

“People entered his experience because they had had it themselves. He gave them the words to express it.”

Karen Leibnitz has worked in the mail order area of the monastery for decades, taking orders and shipping bonsai pottery to customers. Bonsai has long been one of the industries supporting the monastic community. Father James was one of the monks assigned there for work.

“We both arrived around the same time when they were setting up the mail order department,” she said, her eyes filled with tears. “We got to work together.”

Work meant monotony at times, wrapping pots, watering plants, and even having to start all over again when lightning struck the building in 1997 and set it on fire.

“I think he was who his readers expected him to be. He was a regular guy,” she said.

She additionally got to observe his writing. Those working in the area celebrated with a cake when his first book found a publisher. He would often bring drafts of columns, saying, “read this.” When she went on vacation, he wrote letters to her and her husband.

When the draft of one of his columns made her cry in remembrance of an experience in her own life, “he grinned and grinned and said, that is so cool my writing moved you to that,” she said.

She was the subject in one or two of his columns. “It was rather humbling,” Leibnitz said. “I did something quite simple and you found all this grace in something I did.”

People have called from all over the country to find his books and notecards featuring his photography that were sold in the bonsai area, she said.

“He got to know everyone intimately. That was just his way, his need.”

A visual storyteller

Father James was an insatiable writer, but he had an equal passion for photography where he was a visual storyteller, said John Spink, Atlanta Journal-Constitution photojournalist. Spink, who often visited the monastery and shot photos there, one day was surprised when Father James asked him what he thought about having a photography retreat. Spink said, “That sounds great, but how would you do that?”

Shortly thereafter, with little worry from Father James about a strict format, he, Spink and a third photographer held the first “Image, Faith and Photography” retreat at the monastery. It continues to be held annually.

Father James’ gifts made it possible, Spink said. Those who came were typically a diverse group of serious amateur photographers who may have never been in a monastery before. Father James would combine the presenters’ deeply felt examples from their own photos with dialogue about the craft, shared experiences from the group and implicit teaching about prayer, grace and the nearness of God, Spink said.

The late Father James Behrens was also a talented photographer, and took this photograph at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers. He called it “Light Around Every Corner.”

Father James was extraordinarily knowledgeable about photography, he said, and liked to devote a retreat session to a little-known book of photographs he would uncover or a DVD about the life work of a gifted photographer from outside the mainstream.

“He had a knack for knowing good photography and finding hidden gems of not so well known photographers. … In his own simplicity, he would say, I picked up a couple of DVDs. These things would be fantastic and be just gems, the kind of things scholars would find,” Spink said.

“He had a great appeal. He could have walked into any art college and sat down and talked about photography and the class would have been totally comfortable with it. He was a creative guy. He liked people’s craft. He liked sharing about it.”

He believes the approachable demeanor of Father James effectively taught prayer and God’s presence.

“He really kind of showed us that while we were being just out and attentive and receptive and observing the human experience and God’s creation, we were really coming in tune with his grace,” Spink said.

People come in droves to Trappist monasteries to learn how to pray contemplatively, he said. Through his writing and photography in a faith context, Father James did that too.

“Everybody would hear his observations and hear his conclusions and they were universal. It struck a chord with everyone in the room. Here is somebody just like me, and who sees the ordinary stuff in the world just like me. And yet he sees something beyond the ordinary stuff I see and he helps me see God in it.”

“Father James could just lay it out so simply. He would sit back like your best friend sitting on the couch, make you feel at home. Through your conversation he is basically teaching you how to pray.”

One of the great gifts of life in the monastery, Abbot Augustine said, is living in peace and harmony with others who have widely different perspectives and truly seeing the person in front of you.

“James taught me much more than I ever taught him,” the abbot said. “He was a beautiful person.”

Following Mass, the procession of monks, followed by the congregation, went to the cemetery for the monks just outside the abbey church door and Father James was placed in the earth.