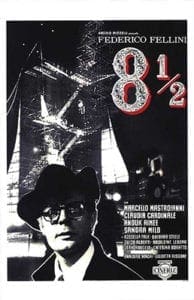

A film painted with a uniquely Catholic imagination: Fellini’s masterpiece ‘8½’

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published June 23, 2017

The challenges we face in life are often made more difficult by difficult people.

The nagging, meddling boss; the manipulator, the gossip and the tedious bureaucrat; the manager who values process over substance: you’ve encountered all of these people.

The nagging, meddling boss; the manipulator, the gossip and the tedious bureaucrat; the manager who values process over substance: you’ve encountered all of these people.

In thwarting our imagination and our ambition, they not only frustrate us; they threaten our sense of vocation and stifle our creative energy. They can jeopardize our potential as human beings, if we let them.

All of these detractors and naysayers are on full parade in Federico Fellini’s 1963 autobiographical masterpiece, “8½.” Yet the film is a triumph not because of its exposure of the bad people, but rather because of its affirmation that we have the ability, with the aid of an intercessor and a little mystery, to overcome pettiness and pride with faith, hope and love.

When he began shooting the film that would later become “8½,” Fellini was much like Dante: “In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to my senses in a dark wood, for I had lost the way.”

Some of his greatest successes were behind him. “La Strada”—Pope Francis’ favorite film, by the way—had been an international sensation, lauded even by the Vatican as a testament to the transcendent power of the cinema. Yet “La Dolce Vita” had created scandal; the same Church which had praised Fellini’s earlier work now condemned his latest film.

Middle-aged and bewildered, Fellini began to make his new film only to find that he had in fact nothing to say.

As Fellini himself recalled, “In the case of ‘8½,’ something happened to me which I had feared could happen, but when it did, it was more terrible than I could ever have imagined. I suffered director’s block, like writer’s block. I was at Cinecitta, and everybody was ready and waiting for me to make a film. What they didn’t know was that the film I was going to make had fled from me. I couldn’t find my feelings.”

Hounded by producers, besieged by critics, and mistrusted by his cast and crew, Fellini was about to strike the set and call off the production. Then, in a moment of serendipity, he realized that the difficulties he was facing could in fact become the subject of the film; the film could indeed be about the very making of the film itself.

Thus “8½” came to be the cinematic equivalent of Shakespeare’s reminder that “Our remedies oft within ourselves do lie.”

Titled “8½” as a reference to Fellini’s own previous body of work—seven feature films and a short—the film would become not only his masterpiece but one of the most enduring works of the international film renaissance. Even today, “8½” remains a rite of passage for the serious student of film; it is one of those movies that must be seen, and it is one of the few films that endures in the imagination. There are moments in “8½” so vivid, so memorable, that I can summon the images up from my memory almost verbatim: the traffic jam that opens the movie, the Asa Nisi Masa childhood scene, the marvelous Saraghina sequence, the Marian muse, the carnivalesque procession that closes the film.

I still remember, after Fellini’s death, when the old Screening Room in Lindbergh Plaza ran a continuous double bill of “La Strada” and “8½” as memoriam to Fellini; I watched each film twice, especially pleased that at last I was understanding “8½.”

The film has a reputation as being almost impossible to understand, which is untrue. If you have lived, if you have endured the torment of difficult people, if in spite of everything you still retain your faith, then you can understand “8½.” It is a film about memory, hope, dreams. It is a film about the persistence of the past in the present. It is a film about the eternal, as expressed in art. It is at once a puzzle and a joy. Like Fellini’s own life, which it represents, the film becomes a universal depiction of all life, life that triumphs over adversity.

The narrative thread is simple. Filmmaker Guido Anselmi, brilliantly played by Marcello Mastroianni, has come to a spa to seek relaxation therapy for the creative block that is threatening to shut down the production of his latest film. While at the spa, Guido experiences a series of flashbacks and fantasies that finally reveal to him that the film he wants to make is really unfolding in front of him. All of the difficult people who nag and prod and pester are actually serving to bring forth his movie; paradoxically, his detractors become his inspiration.

As in almost all of Fellini’s work, there is a spiritual essence at the center of “8½.” This is most apparent in the character of Claudia, who becomes symbolic of both the classical feminine Muse and the Virgin Mary. Indeed, this motif of Muse and Mary runs throughout the film, particularly in the brilliant Saraghina memory from Guido’s Catholic childhood. In blending the mythical with the spiritual, Fellini is able to show us our spiritual center as well as our flawed human nature. He is able to depict both our need for redemption as well as the sins from which we need to be redeemed.

Guido is far from perfect, but the fact that he is capable of redemption from his imperfection is what makes us love him. In watching Guido, we are watching Fellini, and in turn we are looking at ourselves. As Fellini said, “The point of departure for the journey I must begin for each film is generally something that happened to me, but which I believe also is part of the experience of others. The audience should be able to identify, sympathize, empathize.”

“8½” is a formalist and expressionist film, yet it is also one of the most playful movies ever made, and it is a delight to watch, particularly when you understand that most of the film takes place in Guido’s memory and imagination. A hint: as you watch the film, pay attention to Guido’s glasses; when he adjusts them, or moves them down his nose, the film is about to retreat into either a flashback or a fantasy.

Along with the Saraghina sequence, the Asa Nisi Masa scene is one of the most memorable in the film. It is a memory from childhood, a flashback to Guido’s bedtime rituals as a little boy. The room he shares with his siblings is decorated with a mysterious portrait. “Say the magic words,” says his sister before they succumb to sleep. “Say Asa Nisi Masa and the picture will move its eyes and we’ll be rich!”

As many critics have pointed out, the phrase Asa Nisi Masa is a nonsensical wordplay, a code in which the root of the phrase is really Anima, or soul.

Guido finally comes to see that pragmatism and process are not the answer to his problems, or to our problems. Unless he can embrace the soul, the essence of who we are, he will be lost. Yet getting past the trivialities, and seeing the genuine depth of human experience, offers a glimpse into the eternal and the redemptive.

“Understanding what makes a thing difficult doesn’t make it less difficult, and understanding how difficult it is can make it more difficult to attempt,” said Fellini of filmmaking. “With each one, I learn more of what can go wrong, and I am thus more threatened. But it is always satisfying when you can turn something that goes wrong into something that is even better. When I cannot correct the problem, I incorporate it.”

Fellini’s films are often compared to the circus, and his movies, including “8½,” are filled with circus imagery. When life itself seems like a circus, we can learn much from Fellini’s art. His love of magic, of wonder, of mystery—all filtered through a unique Catholic imagination—can sustain us even as his simple wisdom offers instruction for our own difficult journeys.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.