Honoring the enduring examples of a president’s legacy

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published January 26, 2017

Myth is more important than truth.

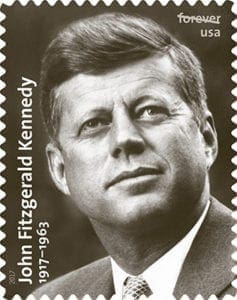

A stamp marking the 100th anniversary of the birth of John F. Kennedy, the country’s only Catholic president, was issued Feb. 20, 2016, at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. The stamp features a 1960 photograph by Ted Spiegel of Kennedy campaigning for president. CNS photo/courtesy U.S. Postal Service

The late William A. Sessions, professor emeritus of English at Georgia State University and a mentor who served as one of my confirmation sponsors, taught me that important lesson many years ago in a graduate Shakespeare class.

“The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones. So let it be with Caesar,” says Marc Antony in “Julius Caesar.”

Professor Sessions led us to see that famous passage in a different way and urged us not to devalue the importance of legacy, legend and myth.

“Myth is always more important than truth,” said Professor Sessions. “Just think of Kennedy.”

A centennial moment

This year marks the 100th anniversary of President John F. Kennedy’s birth, and it is a centennial moment that deserves to be commemorated with respect, gratitude and honor.

More than 50 years after his tragic assassination, Kennedy’s example reminds us of the better aspect of our collective American society.

I was born in the aftermath of Kennedy’s presidency, after Camelot, and in the middle of an era of violence and social upheaval. Kennedy’s example was repeatedly held up to my generation as the epitome of what American idealism and leadership could represent and accomplish.

In the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, Kennedy’s legacy transformed into the realm of mythical: killed as a young man, he endured as a timeless sage; cut down at the peak of American prosperity and optimism, he symbolized the essential vigor of the American spirit. In death, he became an ideal, an icon almost impossible to emulate. Writing about him, even today, means to flirt with both sentiment and hyperbole.

In recent decades—as deconstructive cynicism, skepticism and self-centered pragmatism have served to mar and malign so many aspects of American history—it has become commonplace to debunk the Kennedy myth.

Those who seek to overturn the Kennedy mystique point to his extramarital affairs; our contemporary cult of personality forgets, for example, Kennedy’s brilliant maneuvering in the Cold War and focuses instead on a rumored love affair with Marilyn Monroe.

Conspiracy theories abound, not just about Kennedy’s assassination, but also suspected contacts with organized crime.

Some skeptics continue to doubt the story of Kennedy’s heroics aboard PT-109 in the Pacific Theater of World War II, and “Profiles in Courage”—required reading when I was in school—is still dismissed with a wink as having been ghost-written.

There is some truth to probably all of these accusations and conjectures about Kennedy; there is also probably a good deal of exaggeration.

I don’t really care.

Holding fast to an ideal

Believing in what Kennedy could have been is as important as acknowledging what he really was. If myth is indeed more important than truth, then those who hold fast to the Kennedy ideal actually affirm the possibility that we can indeed be better than we are.

The same man who blundered at the Bay of Pigs in Cuba and who supported the psychotic Diem as president of South Vietnam might very well have preserved the human race. The same man who often hesitated on Civil Rights profoundly influenced his tragic successor, the fascinating Lyndon Johnson, who had the potential—along with Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—to do more for the cause of equality and justice than any other modern politician. The same man who may have led a secretive love life also remains a witness to the grace within physical pain and suffering and the dignity of proudly affirming one’s faith.

To twist Marc Antony’s other words, however, I intend to praise Kennedy, not bury him.

When Berlin was divided, Kennedy stood with his fellow man to denounce tyranny.

When the world literally went to the brink of nuclear war, Kennedy bravely and brilliantly coordinated a masterwork of diplomacy, resorting not to temper but to temperance.

When no one believed in the endless range of the American frontier, Kennedy promised we would reach the moon.

When Kennedy called on young people to serve their country and their world, he supported his rhetoric by creating the Peace Corps.

When the American people needed to be reminded of their deep contributions to the arts and culture, Kennedy publicly promoted the work of the country’s finest writers, artists and musicians.

When people all over the world needed to be calmed, reassured and restored, Kennedy—and his gifted staff—spoke and wrote with a command of English language and rhetoric perhaps never bettered in American political life. Whether or not Kennedy himself really wrote the words “when power corrupts, poetry cleanses,” it is certain that he believed in the transcendent power of language.

And if Americans needed a boost for their self-esteem, they had only look to Kennedy’s elegant wife and his beautiful children, an American royalty fully at the service of the people.

I could go on, of course, and well I know the rebuttals that could be made to all these accolades. Still, I prefer to do as William Faulkner suggested, and “love not because of the virtues, but in spite of the faults.”

He was a Catholic

Most importantly for me, and for my fellow Catholics who read The Georgia Bulletin, is that Kennedy is our first and only Roman Catholic president. The fact remains that Kennedy was a Catholic, he ran the campaign as a Catholic, and he asserted himself as a Catholic even in the face of rampant bigotry and ignorance. He did so with neither piety nor self-righteousness, with neither haranguing nor preaching. He simply, and eloquently, proclaimed himself as both an American and a Catholic.

Our children need to be told the obstacle that Kennedy’s Catholicism presented to his political aspirations. The bigotry that fueled the anti-Catholic resentment of Kennedy’s run for the presidency was ugly and public. Today, much of that hatred simmers underground, hidden away, but that does not mean it does not still exist. Kennedy’s enemies were in full view, and with his unique charisma and strength, he faced them directly. He defended his faith with conviction, with reason, and with courage. At the same time, he affirmed the importance of an American separation of church and state, while he also acknowledged the importance of inclusion and ecumenism. Catholics who were alive at the time of Kennedy’s campaign still remember being proud of him, and he did indeed capture approximately 80 percent of the Catholic vote in the election.

Our country today is a very different place than it was during John F. Kennedy’s presidency. It is not my role to speculate upon what is better or worse, or to assign praise or blame to those persons or cultural trends that have enacted the changes. I am an arts-and-culture columnist, and by no means a political commentator.

As one who believes in the necessity of the imagination, however, I intend to honor Kennedy’s centennial as a testament not to power or politics but rather to the more enduring principles the Kennedy myth embodies and affirms.

When thinking of Kennedy, I can’t help but also think of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and not because Fitzgerald was Kennedy’s middle name.

If any American writer understood the persistence of myth and the endurance of the past, particularly as they relate to the tragedy of an individual life, it was Fitzgerald.

Writing of the doomed yet unforgettable Jay Gatsby in his novel, “The Great Gatsby,” Fitzgerald might as easily have been describing Kennedy: “I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it.”

And like Gatsby, when we confront the Kennedy myth, we too are compelled to “believe in the green light.” We, too, are called to “beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

As Chief Justice Earl Warren concluded his eulogy for Kennedy, “now that he is relieved of the almost superhuman burden we imposed upon him, may he rest in peace,” even as our memory of him must always endure.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.