Portaits of the Black American candidates for sainthood are presented at the altar of Sts. Peter and Paul church before the Sojourning On the Road to Sainthood event. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

Atlanta

Advocates urge canonization for the ‘Saintly Six’ Black Catholic pioneers

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published October 19, 2023

ATLANTA—A group of pioneering Black Catholics, who served with love and devotion in the face of racism and injustice, are at the center of an effort by advocates to urge Pope Francis to expedite canonization. The six African American candidates for sainthood are known collectively as the “Saintly Six.”

Though some have earned venerable or servant of God titles, supporters believe they deserve to be honored as saints for their courageous work educating and caring for marginalized communities.

These trailblazers of the Black Catholic community “left us a legacy of love, of resistance and of true Catholicism,” said historian Shannen Dee Williams

There are some 3 million Black Catholics in the United States, according to Pew Research, but there has never been a recognized saint from the community.

Now, supporters are ramping up efforts to raise the candidates’ profiles to spur Catholic leaders into action.

The candidates on the path to sainthood are Venerable Pierre Toussaint, Servant of God Mother Mary Lange, Venerable Henriette DeLille, Venerable Augustus Tolton, Servant of God Julia Greeley and Sister Thea Bowman.

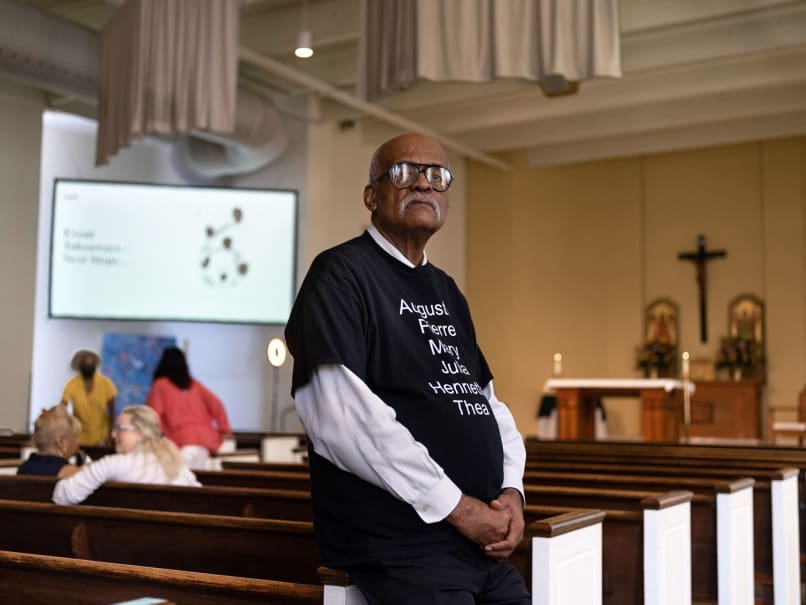

“They kept their faith; they kept their eyes on God. They were people for others, not people for themselves,” said Ralph E. Moore Jr., one of the movement leaders hoping to advocate for their cause to the highest levels of the church.

Each dedicated his or her life to service, embraced the faith with courage, and through witness, encouraged fellow believers to see every person made in God’s image. With all that, Moore said they encountered resistance from fellow Catholics.

Father Bryan Small said the faith history of the six women and men is essential to all believers.

“These six men and women don’t tell a Black story. They tell an American story through Black eyes,” said the pastor of Sts. Peter and Paul Church, Decatur, one of the predominately Black parishes in the Archdiocese of Atlanta. The parish recently hosted Moore for an event to promote the six by telling their stories to galvanize community support.

Ashley Morris, the director of Black Catholic Affairs at the Atlanta Archdiocese, said the six “did simple things that had an extraordinary impact on the lives of the people they served and walked with.”

Prayers, petitions offered for expedited canonization

Joi Parks of KPCLA Court #313 of the Ladies Auxiliary of the Knights of Peter Claver sits in the sanctuary of Sts. Peter and Paul Church before the Sojourning On the Road to Sainthood event. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

At Decatur’s Sts. Peter & Paul Church, a crowd filled the pews on a recent Saturday morning. Parish members have been immersed in the lives of these faithful six for years. During the 2020 pandemic, the parish formed six small faith communities and adopted the women and men as patrons to unite the community when activities were locked down.

“African Americans have been Catholic since they were brought over to this country. And, we know they have led exemplary lives and made contributions to the church and their community,” said Joi Parks, who has been a parish member for nearly 30 years.

“We want them to learn African Americans do want representation and recognition from the church. And so, we should advocate for these candidates.”

Brenda Goode found inspiration in the life of Servant of God Julia Greeley, who emerged from a life of slavery. With her freedom, Greeley relocated to Denver, where she supported poor families in her community. To support them, she personally begged for food, fuel and clothing. Much of her charitable work occurred during the night, saving families from potential embarrassment.

“She just went out there, and she was just a strong woman and always just helped,” said Goode. She is the grand lady of the Knights of Peter Claver Ladies Auxiliary, Court 313.

At the September gathering, Moore and others discussed returning to the church’s ancient custom of elevating people to sainthood by popular affirmation. The group circled the sanctuary to pray a living rosary.

Part of the advocacy has been prayers and petitions to the Vatican to expedite the causes of these candidates. Moore encouraged people to participate in a letter-writing campaign to challenge the church, which has erected roadblocks instead of acknowledging the faith of its Black members in the United States, he said.

“Those are pro-Gospel letters,” said Moore.

He attends St. Anne Church, Baltimore, where its social justice committee launched the initiative. Three of its members are traveling to Rome on Oct. 31 to meet church leaders with the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints. The plan is to hand 1,000 letters to the Vatican leaders. The group already mailed 3,000 letters to Pope Francis, Moore said.

“We’ve always had to keep our eyes on God and not on the institutional church,” said Moore. “The institutional church has been a consistent no to us.”

These six people persisted in the face of resistance, he said. “We think that God wants us to stay with the Catholic Church as a witness to what God is all about.”

Oblate Sisters: educators amid slavery, exclusion

Historian Shannen Dee Williams authored the book, “Subversive Habit: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle,” about the history of Black Catholic religious communities.

She had another book in mind. But when she saw a photo of four Black nuns wearing habits, she changed her focus. She had never known of black Catholic religious communities, although she had been a Catholic all her life growing up in Savannah.

“I’d never seen Black nuns before, and I felt deeply ashamed. How was it possible that I was a Black Catholic woman and didn’t know this history? And although I was ashamed, I soon realized that I was not alone,” said Williams. She published the 424-page history book in 2022.

Through her research, the University of Dayton professor traced the sweeping impact of Mother Mary Lange. Three decades before the Civil War, she began a religious community in Baltimore that stands as one of the oldest in the United States. She was born Elizabeth Lange and raised in Cuba. By the early 1800s, she had settled in Baltimore, at the time, the unofficial capital of the Catholic United States as the first diocese in the young country. Catholic leaders took more than 10 years to accept their religious institute. Still, in July 1829, Elizabeth and three other women professed their vows and became the Oblate Sisters of Providence.

Dr. Gwendolyn Dean listens to speaker Ralph Moore Jr. at Sts. Peter and Paul Church during Sojourning On the Road to Sainthood. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

Elizabeth, the first superior general, took the religious name of Mary. Lange died on Feb. 3, 1882, at the age of 92 or 93. Today, there are approximately 80 sisters serving in Baltimore and Costa Rica.

There was no free public education for Black children in Maryland until 1868, so Mother Mary responded by opening a school. In another first, the community accepted women born into slavery into the school and religious community when others did not.

“They make possible generations of African American women and girls who are called to religious life. They preserve the vocations of thousands of Black women and girls called to religious life not simply from across the United States, but also from Canada, Latin America and the Caribbean.”

Williams said this community is a counter witness to the idea of excusing the slave-holding Society of Jesus and other Catholic institutions that profited from enslaving women, men and children as people of their time.

“Telling the story of Mother Mary Lange and her Oblate Sisters of Providence reminds us they are also people of those times,” Williams said.

Three communities of religious sisters in the United States originated from the Oblate Sisters. The Sister Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary opened three colleges and universities. However, the community chose to overlook its African American heritage by neglecting the role of the founder, Mother Theresa Maxis Duchemin, one of the original four charter members of the Oblate Sisters, said Williams.

The history of the Oblate Sisters reveals the “painful history of slavery, segregation and exclusion” endured by Black women who only desired to live their religious call, she said. For Williams, the Black sisters’ role shaped Catholicism. They were leaders in desegregation efforts, educators of Black history, protectors of children after racist violence and integrated Catholic universities, she said.

The legacy of six believers

Despite the racist oppression, Moore said the Black community has kept its “eyes on God,” while the church leaders put up roadblocks.

And one scholar said while the history is not well known yet, learning from it offers a lesson for the entire Catholic community. Greg Hillis, the executive director of the Aquinas Center for Theology at Emory University, said, “This vital facet of American Catholic history needs to be studied and understood by all.”

Portaits of the Black American candidates for sainthood are presented within the sanctuary of Sts. Peter and Paul Church. From left are the portraits of Mother Mary Lange, Sister Thea Bowman and Venerable Pierre Toussaint.Photo by Johnathon Kelso

“The American Catholic Church has never sufficiently grappled with its history of racial discrimination. The work of reconciliation can only begin when light is shed on that history,” he added.

For Father Small, these six believers, and their perseverance to hold to the faith in the face of adversity, serve as an inspiring example for the church to live up to its Gospel call.

“They serve as a witness to a church that succeeds and fails, often simultaneously. It’s a prophetic reminder, through their witness, of what the church is capable of when we trust our better instincts,” he said.

Morris, the director of Black Catholic Affairs at the Atlanta Archdiocese, said many people are excited to promote the women and men, spreading the word about their examples of Christian witness.

“I think the work ahead of us really involved venturing out beyond our comfort zones to speak courageously about these individuals and their causes,” he said.