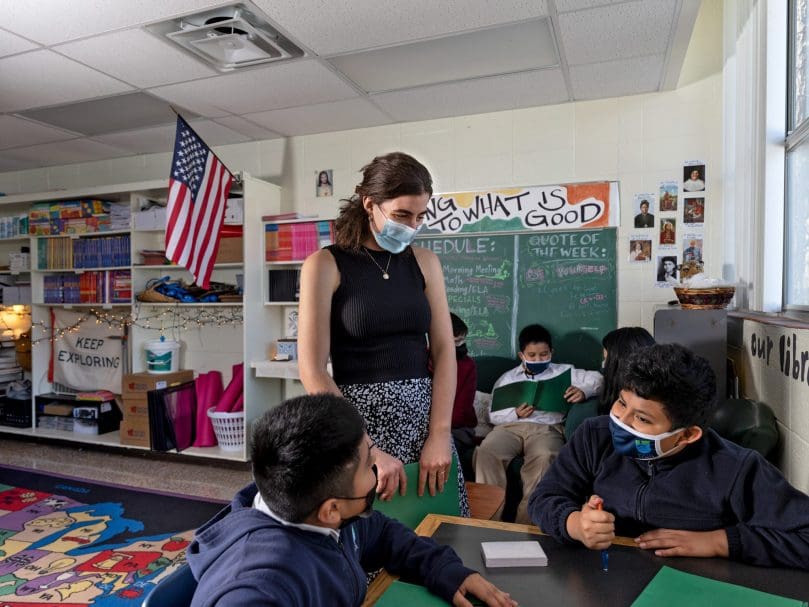

Alliance for Catholic Education Fellow Olivia Anderson helps her students at St. Peter Claver Regional School in Decatur. The program, coordinated through the University of Notre Dame, places teachers in underserved Catholic schools. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

Decatur

ACE fellows ‘on fire’ for teaching and the faith

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published January 20, 2022

DECATUR—Wearing an oatmeal cable knit sweater with elbow patches, Chris Lembo wrote on the blackboard leading the room of eighth graders at St. Peter Claver Regional School through algebraic equations.

“Let’s try something a little more fun, not that this isn’t already fun,” he said to the 13 masked students, as some came to the board to solve equations. Wandering among the desks, he gets into a conversation about the latest Spiderman movie.

Lembo is one of six young adult community members teaching in area schools. Each lives off a modest stipend while earning a master’s degree from the University of Notre Dame with the Alliance for Catholic Education (ACE).

At a time when more young adults are not attending Mass regularly, these Catholics are part of a small group of peers serving the church outside parish life. A recent survey by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate based at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., reported about 9 percent of Catholics between 18 and 35 participate in what it termed a religious institute volunteer group.

Growing by facing curveballs

Olivia Anderson’s fifth-grade class takes a brain break with a game of Pictionary. Students draw an assigned word on the smartboard as their classmates guess the word and recite its spelling. Anderson calls her class “my friends” as she moves the students from math assignments to sitting on the rug reading about naturalist Henry David Thoreau.

Between planning for the rest of the day and making photocopies, the Pennsylvania native eats lunch at her desk.

Her favorite part six months into the program has been “creating a classroom that my kids can feel like they’re heard and loved, and they can learn,” said Anderson, 22, who studied visual communications and design as a Notre Dame undergraduate.

“Hundreds of things could go wrong every day, but it’s been kind of great. I feel with every curveball that gets thrown, I’m more ready for the next curveball,” she said.

ACE Fellow Christopher Lembo interacts with one of his students during class at St. Peter Claver Regional School. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

Lembo studied neuroscience at the campus in South Bend, Indiana, and saw medical school on the horizon. A summer experience in Bangladesh teaching English and boxing prompted him to apply for the ACE program. The 24-year-old Lembo, who grew up in southern California, will finish the program and earn his master’s degree in education this summer. He hopes in the fall to teach internationally in Chile or return to Bangladesh.

“I have a love for education. I love teaching. I love being around kids. I just find so much energy from them. I find it to be a whole lot of fun, more fun than I even expected,” he said.

Faith inspired the young adults to seek out this opportunity, as it combines spirituality and professional development. Anderson said her belief encouraged her to take on the challenge.

“Faith is what invites me to do hard things,” she said.

ACE teachers have gravitated to Atlanta’s Immaculate Heart of Mary Church for worship.

Recruiting teachers for Catholic schools

Schools in the Archdiocese of Atlanta have hosted teaching fellows from Notre Dame University’s Alliance for Catholic Education for more than a generation.

The six fellows are in classrooms at St. John Neumann Regional School, Cristo Rey Atlanta Jesuit High School, St. Peter Claver Regional School, St. John the Evangelist School and Our Lady of Mercy High School.

Mr. Lembo’s desk at St. Peter Claver Regional School, where he is a teacher in the Alliance for Catholic Education program. Photo by Johnathon Kelso

The ACE at Notre Dame began in the early 1990s. John Schoenig, the senior director of teacher formation and education policy (and former ACE teacher), said the program taps into young people’s passions. The program wants young people “on fire for learning, on fire for their faith,” he said.

It assigns teachers to schools in 31 dioceses. Some 2,000 women and men have gone through the program, with less than 100 chosen a year from several hundred applications.

“We’re serving children and families by providing a community of educators,” he said.

The young adults work as teachers for two years and earn a cost-free master’s degree in education from the university.

“It is an opportunity to serve a grave need in our society, that is the need for great teachers, but to do so, surrounded by support, multiple layers of support,” he said. Surveys have shown some 70 percent of participants within five years of the program are still teaching in Catholic settings, he said, with ACE graduates taking on educational leadership roles as superintendents.

Leading by example

At Lilburn’s St. John Neumann Regional School, middle school social studies teacher Alison O’Neil, who has a passion for international foreign policy, started a program called “Cursive & Cookies.” When the school planned to emphasize cursive in student assignments, O’Neil organized the afternoon club for students with public school backgrounds who weren’t as familiar with cursive. Students complete a worksheet of cursive writing and get a sweet reward.

Other ACE students also lead extracurricular clubs. Lembo started the girls’ volleyball team, assisted by Anderson, in addition to leading the school’s Kilometer Kids running club.

On a recent Friday, O’Neil took Polaroids of students to add to the growing collection posted on the wall. Students can earn a snapshot by finishing a current event presentation to the class.

O’Neil is wrapping up her time in the classroom. She studied political science at Notre Dame and is applying for graduate school to study international relations. The only daughter of two lawyers, O’Neil, 23, said she pursued the teaching program in part to give back for the excellent teachers she had growing up.

Alison O’Neil is serving as a middle school social studies teacher at Lilburn’s St. John Neumann Regional School through ACE.

“I always really liked school, and I always really liked academics,” she said. “This has been a chance to take that knowledge and apply it to something that helps people. That’s been really meaningful.”

The fellowship places teachers in the classroom for two years and the school communities go through a “grieving period” when they depart, said St. Peter Claver Regional School Principal Susanne Greenwood. She called it a leading teacher preparation program, and the teachers both educate and inspire their students as role models.

Dr. Julie Broom, the principal at St. John Neumann School, said she’s seen ACE teachers’ enthusiasm as they implement new strategies in education and bring passion for its purpose.

“You learn something different from each new teacher,” Broom said.

Community life brings camaraderie

Outside the classroom, the teachers can be found together in their shared Atlanta house, a modest four-bedroom ranch, off of Shallowford Road. The living room with wood-paneled walls and large worn sofas is the hub of the community. They gather to grade papers and watch TV. Movie posters and other bric-a-brac from past residents decorate the house. Books line a shelf including “Persuasive Pro-Life,” a memoir by death penalty opponent Siser Helen Prejean, and “Chicken Soup for the Teacher’s Soul.” A colorful cross hangs on the wall.

Each week, the six fellows gather for dinner, in addition to nights reserved for a community activity and one for prayer. The responsibility to lead each activity rotates among the housemates. One prayer night Lembo read a Gospel passage slowly and reflectively, inviting people to share a word which struck their hearts. Anderson once bought the house Indian food on her evening to prepare dinner.

The shared living opens each to “camaraderie and solidarity,” Anderson said. The teachers face hardships and bright spots, so the community celebrates and suffers together, she said.

O’Neil said she’s been grateful for the communal emphasis of the program, making her appreciate people’s different needs.

“If everybody thought the same way the world would be really boring,” she said.

Lembo said sharing the classroom experiences of “being thrown into the deep end” brings them together at home.

“I’ve grown incredibly close with each of these people. That’s another thing that I will absolutely take away,” he said. “I plan for all these people to be at my wedding.”