Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderLaGrange

LaGrange’s police chief honored by St. Thomas More Society

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published October 17, 2019

LAGRANGE—Louis Dekmar wants to “interrupt the past” to reconcile and repair relations between law enforcement and the African American community.

Dekmar, the longtime police chief of the City of LaGrange and parishioner of St. Peter Church, set in motion something almost unheard of. He stood in front of a black church congregation in this city some 70 miles southwest of Atlanta and apologized for a 1940 lynching that implicated his department.

“The police department had been involved in a lynching, either through omission or commission,” he said speaking in a conference room at the police department. Dekmar, who is 64, wears his police chief uniform with his black and grey hair cropped short.

Dekmar’s apology earned him many accolades. But he credited the event at the Warren Temple United Methodist Church to a community effort. He said the local NAACP and a biracial group, Troup Together, drew people together for city leaders to acknowledge the decades old injustice.

An apology to right a wrong

The St. Thomas More Society, an organization of Catholics working in the legal profession and judiciary, honored Dekmar with its St. Francis of Assisi Award Oct. 10.

Others recognized by the organization at its annual Red Mass were Georgia Supreme Court Justice Robert Benham with the St. Thomas More Award for promoting and raising the level of professionalism among Georgia’s lawyers and attorney Susan Jamieson, the founder and former director of what is now the Disability Integration Project for protecting the rights of disabled persons in institutions.

LaGrange’s Chief Louis Dekmar has been a police chief for 28 years. Under his leadership his officers have always emphasized community policing, but he said the department’s Trust Initiative is more deliberate. Dekmar, a member of St. Peter Church, LaGrange, is the 2019 recipient of the St. Thomas More Society’s St. Francis of Assisi Award. Photo By Michael Alexander

Dekmar addressed the LaGrange community at a 2017 reconciliation service. He spoke about his department’s lack of protection that led to the lynching of Austin Callaway. The historic Warren Temple United Methodist Church held Callaway’s funeral and it was the site of the Dekmar’s full-throated apology.

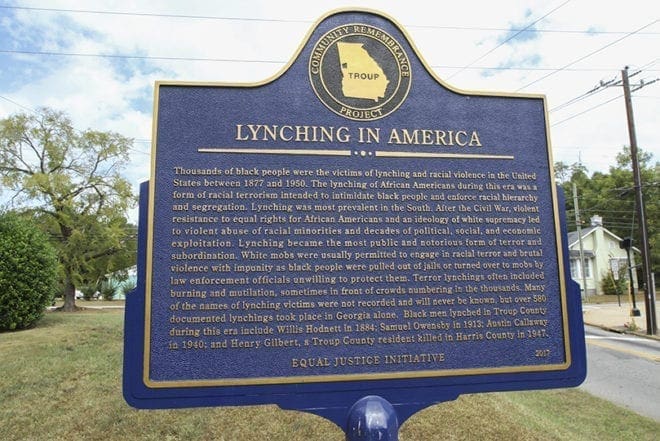

A marker sits on the church grounds, memorializing Callaway and three other men who were killed in the area: Willis Hodnett, Samuel Owensby and Henry Gilbert. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, more than 4,000 racial lynchings took place in the United States between the Civil War and World War II.

LaGrange is 49 percent African American, the largest single racial group, in the city of some 30,000 people, according to the census.

Callaway, a young African American, was arrested on charges of “attacking a white woman” and was awaiting trial in jail, said Dekmar, who is white. However, the veteran cop said the allegations were vague, considering the Jim Crow era.

“This young man was arrested for assault on a white woman, which in 1940, could be anything from a physical attack to failing to avert your eyes when he passed by,” he said.

“What should have been the safest place in the world, they were able to kidnap this young man,” Dekmar said. “There was no indication or record that showed there was any search for him, that there was any investigation.”

Faith inspires to look for the greater good

Dekmar, whose father worked in a munitions manufacturing plant in New Jersey, moved to Oregon when his parents divorced. His path to police work began as a scout affiliated with the local sheriff’s office. He remembers doing search and rescue operations to retrieve hikers lost in the Cascade Mountains.

He partly attributes the rescue experience for his career in law enforcement. He learned more about police work with the Air Force, serving in the United Kingdom. He’s been a police officer for more than 40 years. He recently served as president of The International Association of Chiefs of Police. He and his wife, Carmen, who works in a local hospital, have two grown children.

Dekmar said he leaned on his Catholic faith to guide him along the path toward the African American church.

“We all have a social obligation. When we see something that needs to be worked on, should be addressed or to be improved, you have an obligation to, for the greater good, to address those things you know you can influence, or you can engage,” he said. Plus there is always “Catholic guilt” to do more, he said.

He credits his maternal grandmother for her influence of faith. Left a widow after a mining accident killed her husband, she persevered as an immigrant from Hungary who learned the language to clean houses and waitress while caring for a daughter with polio.

“As a child, you have any kind of challenge, you know, she would just remind you that your faith in God will get you through,” he said.

Taken at gunpoint

The origins of Dekmar’s apology was a conversation overheard between two elderly African American women in the police department looking at black and white photos of police officers.

“They killed our people,” one of the women was heard to say.

A colleague of Dekmar’s told him. He had been there at the time for 22 years and had never heard of the murder.

That sent him on a chase to learn about the murder with few records. No police arrest log to review. No custody records to examine. No jail report to backtrack. He found snippets in newspapers with national coverage, like the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune, the New York Times.

In the presence of community, faith-based and government leaders, this historic marker was unveiled on March 18, 2017 by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) to commemorate the lynchings of African Americans in Georgia’s Troup County. The marker can be found on the side of LaGrange’s Warren Temple United Methodist Church. According to the EJI, over 4,000 lynchings of African Americans took place across 20 states between 1877 and 1950. Nearly 600 occurred in Georgia. Photo By Michael Alexander

Here’s what Dekmar learned. Callaway was arrested Saturday, Sept. 7, 1940. His age is unknown but believed to be from mid-teens to early 20s. He was held in the basement jail cells of downtown City Hall. The old cells are now storage rooms.

Five or six hooded men showed up and took him away at gunpoint. Callaway was found hours later outside of the city at a place called Liberty Hill Road. He had been shot five or six times. Callaway died at a local hospital a short time after he arrived.

Trust Initiative takes root

Seventy-seven years later, community leaders apologized at the African American church.

Dekmar said he faced push back, from the white community with accusations of stirring up the past and from the black community skeptical of his words as window dressing.

The chief hoped the effort improves relations because cooperation leads to safer communities and better policing.

The community formed what’s called the Trust Initiative.

“We’re still able to do our job and hold people accountable in terms of them appearing in court, but not further exacerbate their life,” he said about changes fostered by the effort.

It has focused on reviewing policies that Dekmar said caused needless complications for the poor. For instance, a person would no longer be held over a weekend for a minor offense. Instead, police would arrest, make a record, then release the offender. People’s jobs aren’t now at risk because they could not afford a bond, he said. It revised employer background checks. The department hired a caseworker to help people released from prison.

Dekmar knows blacks and whites have different experiences of policing. Whites tend to be more trusting, seeing a problem police officer as an individual within a fair system, he said.

But not in communities where police are looked at as heavy-handed, he said.

“It’s not something that they look at in a silo. It’s a bad outcome on a page of bad outcomes in a book of bad outcomes in a library of bad outcomes. And so there’s an accumulation of wrongs,” he said.

Dekmar’s words cannot rewrite history. But words and actions from the heart can shape future outcomes, he said.

“We can’t change history. But by addressing it, we interrupt history. And we put a stop in that history to show that, okay, that was then; this is now.”

Learn more about the other Red Mass honorees, Justice Robert Benham and Susan C. Jamieson.