CNS photo/The Trinity Forum

CNS photo/The Trinity ForumWashington, DC

Author: Christians need ‘some distance’ between them, ‘chaotic mainstream’

By JULIE ASHER, Catholic News Service | Published April 6, 2017

WASHINGTON (CNS)—Author Rod Dreher’s critics call him an “alarmist” for proposing that Christians today “put some distance” between themselves and “the chaotic mainstream,” or Christianity will not survive.

Those critics are right, he said.

“I am alarmist about the state of our culture and of our civilization and the condition of the church within it,” Dreher told a Washington audience. “If you’re a faithful Christian and you’re not alarmed, I think you’re failing to pay attention, you’re failing to read the signs of the times.”

“I do not claim ‘the’ world is coming to an end. … What I am claiming, though, is that ‘a’ world is coming to an end,” he explained. “And if believing Christians don’t take radical action right now, the faith that made Western civilization will not survive for long into Western civilization’s post-Christian phase.”

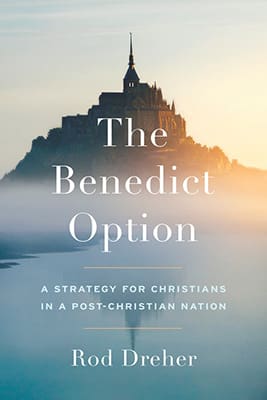

Dreher, currently senior editor at The American Conservative and author of several books, has written “The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation.” He spoke about his book at the National Press Club at an evening event sponsored by the Trinity Forum March 15.

Dreher, currently senior editor at The American Conservative and author of several books, has written “The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation.” He spoke about his book at the National Press Club at an evening event sponsored by the Trinity Forum March 15.

He said the term “Benedict Option” comes from “the famous final paragraph” in philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre’s 1981 book “After Virtue.”

In that book, MacIntyre explains “how Enlightenment modernity overthrew the old traditional source of moral order rooted in Christianity and classical philosophy,” Dreher said. “But it could not produce an authoritative binding replacement for it. The West, in MacIntyre’s view, has been unraveling for some time now and it’s finally reaching a point of reckoning.”

Dreher also quoted a “noted public intellectual” who once said, “It is obligatory to compare today’s situation with the decline of the Roman Empire,” and who lamented “the collapse of the spiritual forces that sustain our civilization.” It was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI.

Dreher strongly believes the “reckoning” MacIntyre described is a clarion call that Christians need to “put some distance” between themselves and “the chaotic mainstream,” and what has been a “steady erosion of authentic Christianity by the relentlessness of individualism, hedonism and consumerism” in the culture.

“The West is living through a time of unprecedented peace and prosperity, (but) there is a mounting sense of political crisis throughout our civilization,” Dreher said. “The signs also of our spiritual depletion are impossible to deny, and if we are spiritually depleted and morally exhausted, our peace and prosperity will not long last.”

“The Christian faith is flat on its back in secular Europe,” he continued. “The United States has long been thought of as a counter-example to the secularization thesis, but that’s no longer tenable” as “the U.S. is on the same downward path to disbelief pioneered by our European cousins.”

Back to where St. Benedict began monasticism

Dreher pointed to statistics including a Pew Research Center study showing that one in three 18- to 29-year-olds in the U.S. has put religion aside, “if they ever picked it up in the first place.” Another study showed, he said, that among 18- to 23-year-old Christians surveyed, “only 40 percent said that their personal moral beliefs are grounded in the Bible or some other religious sensibility.”

For his book—and some lessons in how Christians today can “start the rebuilding, the reseeding and the renewal” of church and society—Dreher interviewed the Benedictine monks in Norcia, Italy. Their founder, St. Benedict of Nursia, patron saint of Europe, was the fifth-century father of Western monasticism. He founded monasteries at a time when Europe was experiencing a crisis of values and turmoil caused by the fall of the Roman Empire, decadence and the death of traditional customs.

“Monks moved all over barbarian-ruled Europe,” Dreher said. “They brought the faith to unchurched people. They taught them how to pray, but they also taught the peasants how to make things, how to build things, how to grow things, skills that had been lost in Rome’s collapse, and in their rituals and in their libraries, the monks kept alive the cultural memory of Christian Rome.”

He interviewed Father Cassian Folsom, Norcia’s prior at the time, who told him “the forces of dissolution from popular culture are too great for individuals or families to resist on their own. We need to embed ourselves in stable communities of faith.”

Not total withdrawal, but strategic separation

So “does the Benedict Option call for all Christians to head for the hills,” as St. Benedict did when he fled Rome, or to “build high walls to keep the impurity of the world far away? Not at all,” Dreher said. “Let me underscore this: not at all.”

“We have to evangelize. We have to serve the world, or we are failing the great commission,” he explained. “We have to serve our neighbors or we fail to serve our Lord. Put all thoughts of total withdrawal out of your mind.”

The Benedict Option calls for “a strategic separation from the everyday world,” he said. “We have to erect some walls, so to speak, between ourselves and our communities and the world for the sake of our own spiritual formation and discipleship.”

He said Christians must strengthen their churches, start schools, build up the local community, and, “to stay true to our faith,” must listen to “ … authoritative voices from the Christian past, especially the pre-modern era, including most of all the early church.”

“If the church is going to be a blessing for the world that God means for it to be,” Dreher continued, “then the church is going to have to spend more time away from the world deepening our commitment to God, deepening our knowledge of Scripture, deepening our relationship to the tradition and our knowledge of the historic Christian church, and thickening our relationship to each other. We Christians cannot give the world what we do not have.”

“We should engage with the world but not at the expense of our fidelity and our sense of ourselves as a people set apart,” he said.

Christians still have to stay active in conventional politics, he added, “working, as we are able to, for the common good.” One crucial fight is “to protect religious liberty upon which so much depends,” Dreher added.

He closed with some words from Father Folsom, who told him “if Christian families, churches and communities in the West do not do some form of the Benedict Option, then ‘they’re not going to make it.’