Atlanta

High school integration meant an Atlanta black Catholic could ‘come home’

By GRETCHEN KEISER, Staff Writer | Published January 9, 2014

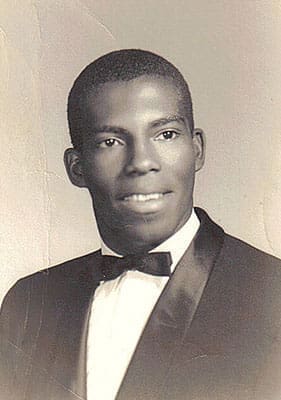

Charles Moore

ATLANTA—Charles Reginald Moore was the first African-American to graduate from St. Joseph’s High School in Atlanta. Entering in the fall of 1962, when the first black students desegregated Catholic schools in the Atlanta Archdiocese, Moore came in as a junior. He graduated in 1964 from the archdiocesan high school, which was then located on Courtland Street.

In a telephone interview with The Georgia Bulletin, Moore, who is now retired and living in Florida, said he was the only black in the class of 1964 at St. Joseph’s. Growing up on Camilla Street in Atlanta’s West End, his family sent him to live in Detroit with an uncle when it was time for high school, he said, because there was no Catholic high school in Atlanta that accepted black students. In Detroit he was able to attend St. Leo’s, an integrated Catholic high school. Then his mother, Louise Moore, let him know that the archdiocese intended to integrate St. Joseph’s High School.

“I told her I would rather come home and go to school,” Moore said.

In September 1962, a total of 17 black students integrated various Catholic elementary and high schools across the archdiocese. At St. Joseph’s High School, Moore said he and the other black students, who were younger than he, were accompanied to school at first by an armed detective.

“We rode in his car initially,” Moore said, and then, as the integration took place without incident, “I would just catch a bus.”

Documents in the Atlanta Archdiocese Archives show that Atlanta Police Chief Herbert Jenkins offered Archbishop Paul J. Hallinan to provide police protection, as needed, for students who broke the color barrier at the Catholic schools.

Moore played basketball his junior and senior years at St. Joseph’s and said his involvement in sports, and that of other black players, drew racial demonstrations at times. The Catholic team didn’t play the Atlanta public high schools, he said, but would play small town teams.

“There would be some people demonstrating because I was playing at the games. I might have a threat not to come to the basketball game,” he said, but “nothing really happened to me.”

“There might be some people milling around, yelling, but no fights or anything like that,” he said.

He had played football at St. Leo’s, as a linebacker and fullback, but Moore said he was not permitted to play football in Atlanta.

“At St. Joseph’s they didn’t want me to play. They thought someone might intentionally hurt me,” he said.

His memory is that he “was treated OK” at the high school. “I had some school friends. I never really went to their houses. We might study together.”

“The school was on Courtland. Peachtree was right there also. I’d go down Peachtree to get a hamburger before I went home. I remember this one place they didn’t want to serve me. But at the school it was OK,” he said.

After graduating in the class of 1964, he went to Michigan State University to study business administration. He’d gone to some Michigan State football games and other activities while living with his uncle in Detroit, which made a big impression on him. It was a legendary time for Michigan State football teams, Moore said, as, coached by Duffy Daugherty, the Spartans won national championships and sent top players to the NFL. The undefeated 1966 team played in “one of the historic games of football” with Notre Dame.

“Bubba Smith was playing. He was ahead of me. There were about five or six players that went to the pros after Michigan State. They had a real awesome team,” Moore said.

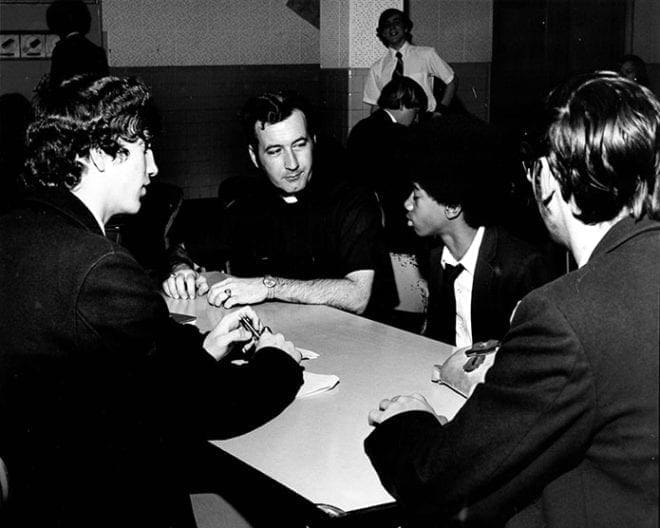

Father Jim Greer is shown with St. Joseph High School students, left to right, Frank Blades, Norman Fletcher and Ken Green in this undated photo in the Archives of the Atlanta Archdiocese.

Going there, “I was thinking of playing football,” he said, but after he got there, “I figured I better just hit the books.”

After graduating from college, he worked at the Cummins company in Indiana, diesel engine manufacturers, and then in Lakeland, Fla., for an engineering and construction company. Eventually he returned to Atlanta in the insurance business, working at different times for Mutual of Omaha, Metropolitan and Delta Life Insurance, where he became a district manager.

In the 1960s, in his close-knit family, people went north “searching for better jobs and better opportunities,” Moore said. “… You might go to school here, but go north. There will be better opportunities for you there. That was kind of the spirit then.”

His prospects seemed limited in Atlanta when he was young, Moore said.

“For the most part when I was growing up, you had to be basically teaching or preaching, a lawyer, doctor, nurse. Things were pretty limited jobwise unless you were in those categories. You might get on at Lockheed or Ford, but you wouldn’t get on downtown at one of the firms or even little stores.”

But as he graduated from college up north, the change was evident, he said.

“When I was coming out of Michigan State, minority folks were getting jobs in big companies. You could see things were changing.”

His memory of Catholic high school at that time of desegregation is positive, he said.

“I was glad to be at a Catholic school. Also mostly I wanted a good education. I thought St. Joseph was a good school. I got a good education,” he said.

Looking back on his experience of 50 years ago, Moore said, “I thought those times were going to change things, which they have. It was like you were part of a revolution—that feeling.”

“I feel like it was part of history.”