Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

Shrine parishioners inspired by pastor’s courage, ministry to war-wounded

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published November 21, 2013

ATLANTA—The Atlanta Zero Mile Marker is hard to find. It’s tucked below a parking deck at Underground Atlanta, usually behind locked doors. But on Sunday, Nov. 17, Irish and American flags and lit candles flanked the yard-high stone marker.

Scores of people from the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception and the Hibernian Benevolent Society of Atlanta crowded this dark, low-ceiling state office building, as trains roared past, to remember an Irish priest credited to have saved downtown Atlanta’s churches and civic buildings during the Civil War.

Some 150 years later, people said the spirit of Father Thomas O’Reilly lives on in the women, men and children attending the historic parish, with its service to the poor.

“We continue to work together for the greater service to the community,” said Shane Murphy, 30, who attended with his wife, Kristin, and toddler son.

With this special ceremony, the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception started a year of observances to commemorate Father O’Reilly, its pastor during the war, and the persevering spirit of the churches. It’ll include a trip to Ireland next fall for a choral performance, along with ecumenical programs bringing together the downtown churches.

This marker is ground zero for Atlanta. It was planted here in 1842 as the southeastern terminus of the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and the settlement grew from here. Father O’Reilly was one of many Irish natives here. The sons and daughters of Ireland moved from Savannah and the coastal region to what was then a frontier town. Starting in the 1840s, large numbers came to this place to work in the booming railroad trade.

At Sunday’s ceremony at the marker, the crowd heard stories from the Civil War detailing life in the war’s fiery aftermath, diary entries of a 10-year-old girl, of Father O’Reilly visiting a dying soldier, and a message from the Georgia Militia commander to Gov. Joseph E. Brown who reported of the safe buildings “all attributable to Father O’Reilly.”

One of those saved churches was Second Ponce de Leon Baptist Church, which moved to Buckhead in the 1930s. Dr. Charles Qualls, an associate pastor for pastoral care at the Baptist church, read Scripture from Malachi during Mass celebrated at the Shrine that morning.

He later said leaders at the Baptist Church would be intentionally talking about Father O’Reilly and his saving actions during the months ahead. More than just saving buildings, Father O’Reilly gave the war survivors “a gathering space, a sacred space,” said Qualls. His church continues to have a steeple bell Union soldier tried unsuccessfully to blow up during the war.

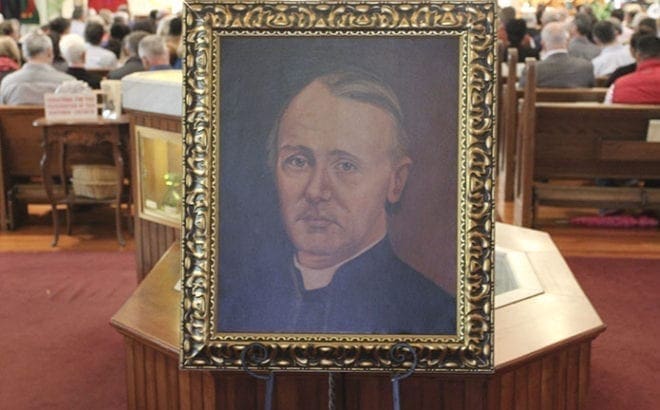

A painting of Father Thomas O’Reilly is displayed in the back of the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Atlanta, during the Nov. 17 Masses. Photo By Michael Alexander

Historians are reconsidering the burning of Atlanta, whether it was deliberate by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. What is undisputed is Union artillery for months bombed Atlanta, which later burned after Sherman captured it and continued his march toward Savannah.

For Msgr. Henry Gracz, the Shrine pastor, the key issue is that Father O’Reilly, who would have been in his early 30s at that time, lived and ministered during the Civil War no matter the color of the uniform.

Myths may have sprung up, but there is little doubt Father O’Reilly was a key figure in Atlanta’s history, he said. A marker to his efforts is at Atlanta’s City Hall.

The sanctuary of the Shrine church, which was rebuilt in 10 years after the war, sheltered the wounded as a hospital during the conflict. The church stood in the heart of the then small city, so the pastor could have crossed paths with military leaders quartered nearby.

David Furukawa and his four-year-old son William were two of the five people who appeared in period uniforms as representatives of the 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Standing in the pew with them is Furukawa’s wife Kathleen, left. Photo By Michael Alexander

Today, Father O’Reilly’s remains are interred in a crypt in the church. He died in 1872 at 41.

Jackie Stephenson, 58, said her parish and its service thrives now because of the legacy set by the priest. “It’s part of our history. The church has a tradition and history of giving,” said the Grant Park resident.

Instead of tending to battlefield wounds, the parishioners today team with Central Presbyterian Church members to help men who live on the streets with their winter homeless shelter. St. Francis Table at the Shrine serves meals to the hungry year-round.

Civil War re-enactor Marvin-Alonzo Greer dressed as a black Union soldier. The 26-year-old Morehouse College student heard about Father O’Reilly during his American history class at Our Lady of Mercy High School, in Fayetteville. For him, Father O’Reilly’s story is about “struggle and resistance.”

Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory, elevating the host during the consecration, was the main celebrant for the Mass commemorating the “bold faith” of Irish priest and Immaculate Conception Church pastor, Father Thomas O’Reilly. Joining the Archbishop Gregory at the altar are Deacon Bill Payne, left, and current pastor Msgr. Henry Gracz. Photo By Michael Alexander

During his time, the Irish were considered a lesser race, not just a nationality, so Greer sees some parallels to the life of black soldiers of those days. It took courage for Father O’Reilly to stand out from the crowd to do what he did, he said.

Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory, at the Mass in the red brick church, said the community is “still indebted to the courage of this immigrant Irish priest who dared to speak up for the people of Atlanta and who cared for the battle-wounded men who would have probably then regarded each other as enemies.”

In his homily, the archbishop reminded the believers about today’s immigrants, who “also provide heroic service to this community and our nation.”

Atlanta is a place “where immigrants still continue to flock, seeking to find the blessings of jobs, a brighter future and the warmth and hospitality that belong uniquely to the South,” he said.

The story of Father O’Reilly’s actions isn’t about the past only, he said. He set a path for the future too, one where “we celebrate all that Atlanta has now become as well as the future challenges that lie ahead for all of us who are proud citizens of this wonderful community.”

Dressed in the blue uniform of the 21st Ohio Volunteer Infantry, David Furukawa said he believes Father O’Reilly’s story holds a message for today.

“It’s about courage and standing up for the things you believe in, even if it’s unpopular. It’s standing up for injustice. I’m sure it wasn’t popular to have soldiers in here. His vocation was to treat everybody,” Furukawa said.