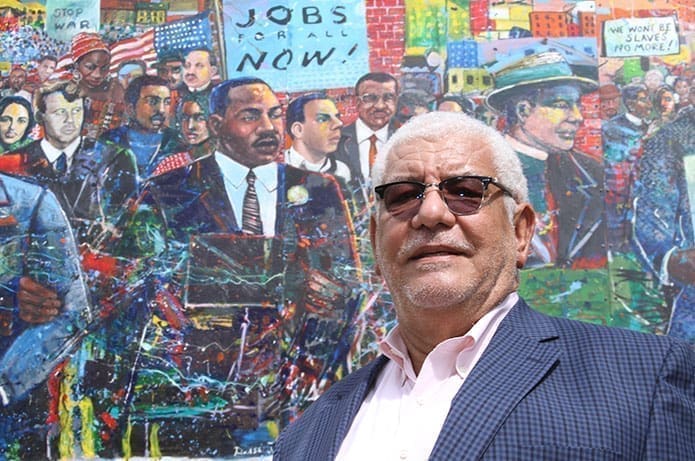

Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

March set direction for his life’s work

By GRETCHEN KEISER, Staff Writer | Published August 29, 2013

Attending the March on Washington 50 years ago solidified the commitment of 22-year-old Charles Prejean to make “human betterment” his life’s work. Prejean, 72, the director of the Office for Black Catholic Ministry, looks back on hearing Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and the unfinished goals of the march.

How did you get to go to the March?

In 1963, I was 22 years old. I had just finished my summer session in college (at the University of Southwestern Louisiana). I was a senior. … A former assistant pastor at my church, Father Albert McKnight, CSSP, and I remained very good friends. … We worked in adult education programs and in starting a credit union as a source of loans for poor people who had trouble obtaining loans from local banks, especially black folks. … We decided to go to Washington for the march. Father McKnight had a nice little station wagon. My younger brother, Fredrick, made a fuss about going and our parents let him go. We brought him and two other young parishioners in their late teens. We got there the day before. The priest had made arrangements for us to stay in a gym at a Catholic school, I believe. We slept on a mat on the floor.

What was it like that day?

We were all excited. The activism in the community was just beginning. The NAACP was being more vocal about voting rights. … High school students were becoming more vocal about having demonstrations (against segregated facilities). We had had a demonstration at a local five and dime store. There was a groundswell of hope. (The Supreme Court decision) Brown v. the Board of Education had passed in 1954. Desegregation was beginning. The local college I was attending had just a few years before opened its doors to blacks. … We still didn’t play varsity football or even intramural sports. It was only partially desegregated.

… We never dreamed we could have an opportunity to go to Washington for this event. We had heard about Dr. King and his work. … We got up very early so we could get over there to get a decent place. … We were still about 50 to 100 feet away from the podium. We were along the reflecting pool as it starts just off the Lincoln Memorial. There were microphones so we could hear all the speeches: John Lewis; the singing; of course, Dr. King’s “Dream Speech.” It was a very electric, very exciting moment for people. There were people everywhere. Folks were happy, joyous, kind to each other. There was no ruckus going on. Folks were excusing themselves if they bumped into you. There was a friendly atmosphere there.

I felt we were part of something historic that was happening. This was sort of like a culmination, the gathering together for jobs and freedom. We felt it was part of what was happening around the nation. … We all came from poor communities. We knew things had to change. We were hopeful that things would change. I was hopeful when we got back the college would be completely integrated. We spent the night at the same place and then went on. … What was on our minds constantly was what had gone on at the march and what would happen in the country as a result. Even the younger ones felt there was a better future for them.

To a certain extent, some of that came true. We think there was a correlation with the passage the following year of the Civil Rights Act. The Voting Rights Act was certainly impacted by the “I have a dream” speech.

Dr. King was certainly the motivational person, the right person at the right time to lead the movement itself.

… As Catholics, we didn’t hear that type of rousing homily at that time. We just began to get snippets of it on television. We were very impressed with that type of rhetoric and very moved by it. He was saying some terrific things. We weren’t asking for anything exceptional. We were asking for what was normal as part of the human estate. What we wanted was what God intended for us. To hear a man of God, a preacher, say those things just confirmed what we all thought—God was on our side.

It was a different time. There was an electricity in the air. What was happening was in a sense a culmination of what happened over the years. It was a culmination of efforts over time, over centuries. All of those efforts began to result in some changes.

Dr. King was the right person at the right time to take the struggle to the next level.

How did it impact your life?

I had never seen that many people before. I was somewhat in shock. Our city, Lafayette, La., had 30,000 to 40,000 people at that time. … My father was from a farming sharecroppers’ background. We had relatives in the country and visited them about every week.

I was impressed with the event and I think it confirmed in me a goal that I had, which was to work for human betterment. I had gone to the seminary first with that in mind. When I left the seminary, after determining God was calling me to be a layperson, I made some steps in that direction. … That experience encouraged me and motivated me even more in that direction. I finished my undergraduate work and taught in a Catholic school for two and a half years. I was also volunteering in the evenings for a cooperative development. I was able to come in as a full-time person in a Lafayette community cooperative, the Southern Consumers Cooperative, a “holding cooperative” that had controlling interest in several subsidiary cooperative businesses. One of the subsidiaries was a statewide credit union, which served as a central lending organization to provide money to other cooperatives in the state. Another subsidiary was a bakery cooperative and others included agricultural cooperatives in rural Lafayette and St. Landry civil parishes. The cooperative business model gave ownership to its members and other benefits, that is, farmers benefited from economies of scale in purchasing and also marketing. In Louisiana we started cooperative enterprises in, I think, four separate communities. That’s how I started. I worked there until about 1967.

The March on Washington was for “jobs and freedom.” We, in our group, were more influenced by the emphasis on jobs and economic development. … There were other folks doing similar things in the South and trying to raise funds. Interestingly, a number of us were soliciting support from some of the same foundations. These thought we could benefit from collaborating with each other so they asked the Southern Regional Council, a progressive Southern organization, to convene a meeting for us. As a result of this, we, community groups working to develop cooperative enterprises in a number of Southern states, created a regional organization that we called the Federation of Southern Cooperatives (FSC). Its mission was to provide training and technical and marketing assistance and some financial assistance to those who were just starting cooperatives. Many were poor people just coming together.

I served on the board of this organization and as its first chairperson. We didn’t have any money to pay an executive director so the other members of the board of FSC asked me to get things started. I moved to Atlanta in January 1968. A few months later we received some grant money, sufficient enough to pay me a salary and bring my family here. The organization had representatives from the major civil rights organizations. We were all doing the same thing. In 1967 we had a meeting with Dr. King who was beginning to talk more and more about economic development. He was planning the Poor People’s Campaign. At this meeting he was impressed with our efforts to develop community cooperatives.

As the executive director of FSC, I managed an operation that at one time had 110 cooperative members spread out over 11 Southern states with a budget of several million dollars. Essentially, FSC provided technical training, marketing, and financial support to its member cooperatives.

The cooperative member businesses consisted of agricultural production and marketing cooperatives; quilting cooperatives; credit unions; housing cooperatives; handicraft cooperatives; fishing cooperatives; a bakery cooperative, etc. We tried to use skills and resources people had to develop businesses and engaged them in these. FSC was chartered to serve in11 Southern states and the District of Columbia. The organization still exists. The credit unions and the agricultural and housing enterprises are still the strongest businesses.

My wife Carmen came from the same hometown. She was an activist. She was out there marching. We have three children and five grandchildren. All of my life I have worked in that area, either teaching or community development or with the Church. The work of evangelization is not so dissimilar to what I have always done.

Were you ever in danger?

The threats were steady, the phone calls, the letters we received. We established a rural Training and Research Center in Sumter County, Ala. It abuts the Mississippi state line. We were there with our very young family. My two kids had to be escorted to their schools because of the threats. There were near misses of violence, as in the case when I and my family had to leave a march to attend a meeting in Jackson, Miss. When we left, the remaining marchers were arrested, put in jail, and beaten.

We lived on the grounds of the research and training center in Alabama, where we lived in trailers in a pasture. We raised money to build the training facilities, which included an administration office, a dormitory, cafeteria, classrooms, and demonstration agricultural projects. We had to haul our drinking water from the county seat, about 10 miles away. One of the values that we came to appreciate from working in this way was the true meaning and importance of trust. Each person needed each other to survive in a hostile environment. We were living out our Christian faith in the service of others, with a minimum of creature comforts, but with the common belief that we were practicing our faith. Nobody ever just worked 40 hours a week. It was around the clock.

The marches we held had to do with desegregating facilities or objecting to exploitive business practices between farmers and canneries and sweet potato factories and objecting to the prices farmers were getting for their produce. In the 1970s exploitive practices were still going on.

Who were your mentors?

Father McKnight was certainly an important role model for me and for others in southwest Louisiana. He ran the Southern Consumers Cooperative and later the Southern Cooperative Development Fund. Father McKnight came to my parish in the early 1950s, as the Holy Ghost Fathers were working in black communities in southern Louisiana. My parish, St. Paul, was at one time one of the two largest church parishes in the country. Father McKnight was like that lightning rod for a great deal of activism in this part of the country. He was the first black priest we had. We also had a group of black priests who were missionaries from the Society of the Divine Word, from St. Augustine Seminary, a seminary founded for the formation of black priests. These also served as role models. Southwestern Louisiana was a very Catholic community, especially among African-Americans. When I was growing up, over 90 percent of the African-American community was Catholic. Other role models were the representatives from some of the major civil rights organizations, from CORE, NAACP, and from other organizations like the Southern Regional Council, the National Sharecroppers Fund, the American Friends Service Committee, etc.

What is your perspective now?

Looking back from the perspective of 50 years, I’ve seen some changes. We can now boast of a more egalitarian society. More blacks are taking advantage of educational opportunities, as well as making advances in the business and professional community. At the same time, there are negative things still out there hindering blacks from improving their conditions. For example, the recent voter suppression laws that some state governments are passing, and the recent Supreme Court nullification of a part of the Voting Rights Act, all seem to be efforts to restrict voting participation, particularly for blacks and other minorities. … We made some gains and now these gains are being taken away. …

There is a need for a similar kind of movement today for jobs and freedom.

Police profiling of blacks and the disproportionate number of blacks, especially blacks in prison, suggest that there is something wrong with our justice system.

Our democratic principles are goals and we are moving in the direction of realizing those principles. These are the ideals that we strive for. Human beings are good and bad. Sometimes the sinfulness in us affects the realization of those principles. Even in the absence of racism, I think you would have these struggles.

… I was drawn to the nonviolent principles. I thought love was a stronger force than hate and eventually it would prevail. It’s important to look on the March on Washington in those ways: Dr. King’s adherence to Gandhian nonviolent principles. Those are the principles that will change conditions. Those are the principles Christ taught us: Love of God and love of neighbor are our two greatest commandments. They are nonviolent principles. They are certainly Christian principles. There is still something to be learned by reflecting on that 50 years later.