Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael Alexander

Atlanta

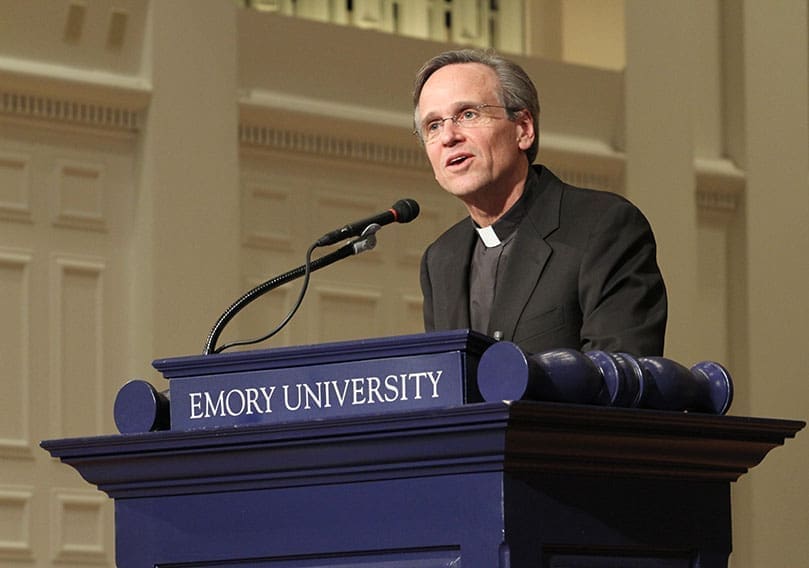

ND President Speaks On Faith Beliefs In Public Square

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published April 28, 2011

The University of Notre Dame president urged Catholics to live their Christian values as the best antidote to bitter partisan political debate.

Holy Cross Father John I. Jenkins, speaking at Emory University, said people of faith must be engaged in politics, but not in a way that gives ammunition to people who do not hold religious beliefs.

The witness a person of faith gives through their personal conduct trumps any cause they champion, he said.

“No political end should overshadow this call to witness, because no work is ever more effective than witness to truly achieving religious ends. Indeed, if love is the greatest commandment, then the way we engage one another in public debate is not a means to an end, but the means are the end,” he said.

A person of faith should approach politics with humility, respecting people with differing political views and steer clear of marrying partisan politics with religious institutions, he said.

Father Jenkins spoke to a friendly audience of 450 on Thursday, April 14, at Emory University’s Glenn Memorial Auditorium, where he received two standing ovations. It was hosted by the university’s Aquinas Center and the Candler School of Theology. He spoke as the second annual major Catholic speaker invited to the university in an ongoing lecture series. The talk was titled “Passionate Convictions and Respectful Conversations: Faith in a Pluralistic Democracy.”

Father Jenkins was elected the president of Notre Dame in 2004, after serving as a member of the philosophy faculty since 1990 and as university vice president. He is a member of the Congregation of Holy Cross and was ordained in 1983.

In 2009, he faced severe criticism, including from many bishops, for inviting President Barack Obama to be the university’s commencement speaker. Opponents complained the president’s position on abortion rights made him unsuitable to speak at the university and receive an honorary degree.

In an interview before his Emory lecture, Father Jenkins said he was interested in the intersection of politics and faith because issues being debated—from embryonic stem cell research and same-sex marriage to abortion—have an important moral component.

Obviously, faith does play a part in those discussions, he said.

“We have to find a way to make our contribution constructive and helpful. Our communication of the faith can play a role without being divisive,” he said.

Catholics are both citizens and members of the faith community, he said.

“We have to play both those roles. We cannot hold them apart. Our faith forms our political life. And we need to do that in an intelligent way and respecting the integrity of faith and, at the same time, being good citizens in a society that has people of many different faiths, or no faith. There are serious ethical issues we have to grapple with together,” he said.

Responding to a question about the president’s speech, Father Jenkins said to refuse to talk to someone in a democracy because of differing views is not part of the church’s tradition.

“The Catholic Church has never been a sect that has cut itself off,” he said.

“We have to persuade. You persuade by trying to understand,” he said.

The document “Faithful Citizenship,” issued by the U.S. bishops before the 2008 elections, is a worthwhile tool for Catholics, he said.

“That’s a good document because it tries to identify key issues without dictating this (political) party or that (political) party. When bishops are thoughtful about this, they tend to recognize these issues are complex, as we all do. There is a moral dimension to our political life and you have to take that seriously,” he said.

During the lecture, he cited the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Philadelphia’s “Project Home,” founded by a nun and laywoman, which has reportedly reduced homelessness in the city by half, as examples of how Christians’ lived values have contributed to the world.

“Our enduring goal should be the impact that comes when people see Christians, or others of other faiths, living the truth of their faith in ways that even non-believers can admire,” he said.

Father Jenkins said passionate Catholics involved in politics should come to issues with humility and with respect for political opponents.

“Charity demands that the person be treated with respect,” he said.

People of faith may feel a great certainty about a political point of view because it is grounded in belief. However, even when one’s political position is grounded in a religious understanding, a person should make the arguments with “a certain humility,” Father Jenkins said.

For one thing, he said, in the history of the Catholic Church, some beliefs that once were strongly held evolved over time: for example, the view at one time that the Earth was the center of the universe and that charging interest on loans was an injustice.

“If such a development occurred in the past,” he said, “we can expect it to occur in the future.”

Also, humility allows a person to hold a belief that is both grounded in divine revelation, but also leaves open the possibility that it can grow. It allows a position to be flexible, open to criticism and to public discussion, he said.

Father Jenkins said Christian witness is most needed during heated disagreements. “(That’s) when we make a genuine effort to treat the other person with respect, to appeal to common values, and to conscience, to win them over.”

“Ultimately, truly Christian attempts to engage one another in public debate must take the form of an effort to persuade,” he said. “People are not persuaded by attacks on their character. But if I don’t try to persuade you—but only try to prove you wrong—then I am not showing the respect that love demands.”

And engaging in dialogue makes it difficult to vilify opponents, he said, adding, “To stand apart, proclaim my position, and refuse to talk except to judge does not reduce evil or promote love. And if it does neither, how can it be inspired by God?”