Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

Archbishop Reminisces, Illuminates Bishop’s Role

Published December 4, 2008

ATLANTA—Atlanta’s Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory was first made a bishop 25 years ago this Dec. 13 in Chicago, serving as an auxiliary bishop under Cardinal Joseph L. Bernardin. To mark the anniversary, the dynamic leader of the 750,000 Catholics in North Georgia sat down recently for an interview with The Georgia Bulletin, to remember the past and reflect on what it means to be a bishop.

Recall when you first learned you were going to be a bishop.

At the time of my appointment I was director of liturgy and a professor at the seminary at Mundelein. And (that) evening … I got the telephone call from the apostolic delegate (to the United States) who was then Archbishop Pio Laghi. …

It was after supper on a Monday, and I was in my room with a young student. It was the beginning of the school year, and he was interviewing me to see if I would be his spiritual director because that was one of the things that I did on the seminary faculty as well. …

So I asked the young man if he’d excuse me for a moment … if I could go and take this phone call. …

Well the switchboard said you have a call from the apostolic delegation. And it was a priest on the line who said, “Is this Father Gregory?” I said, “Yes, it is.” He said, “The apostolic delegate would like to speak with you.” So Archbishop Pio Laghi came on the line. And he said, “Father Gregory, you’ve heard about the need for auxiliary bishops in Chicago” because Chicago at that time only had two and we knew that Cardinal Bernardin had requested additional. We didn’t know when, how many. And I said yes—it was not a deep dark secret. And he said, “Well that’s good because Pope John Paul II wants you to be one.” He said, “You don’t have to accept, but I think you will accept because you are a loyal son of the church.” …

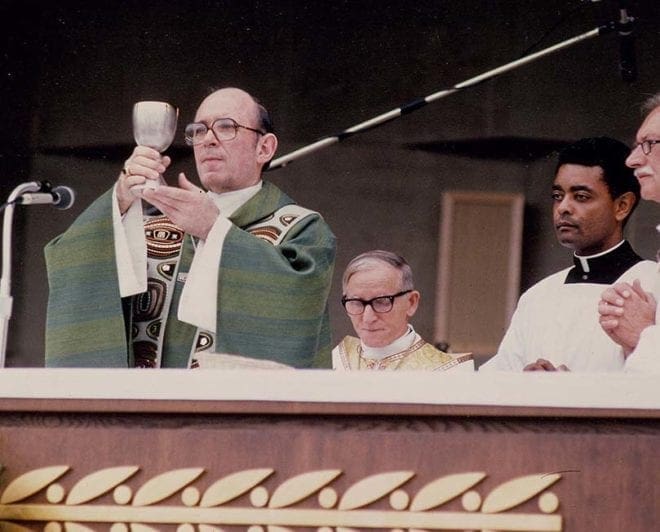

Then Father Wilton D. Gregory, on right, celebrates Mass in Chicago with Cardinal Joseph L. Bernardin in an undated photo. Photo provided by the Catholic New World, Archdiocese of Chicago

So I said that I would accept. And he said to confirm it, I had to write a letter to the Holy Father expressing my acceptance and pledging my fidelity and loyalty to Peter’s successor, and then you send that letter to the delegation to the embassy in Washington.

He told me that it would be announced publicly a week from that following Tuesday. But Cardinal Bernardin was in Rome at the time for the bishops’ synod on penance in 1983. And so what the delegate was doing was securing the acceptance of the candidates that had been chosen, and then he would talk to Cardinal Bernardin to say everything was set.

Well, he said, you can’t tell anyone until it’s public. It’s officially announced by the Vatican. And that was fine. I knew that was the procedure. … So I then didn’t hear anything for a week.

And you had this great secret.

Yes … but I’m good at keeping secrets.

…That following Saturday I get a phone call from the nuncio saying that Cardinal Bernardin wanted to delay the announcement until he had returned from Rome from the synod. … It would be announced on the 31st of October.

So I actually knew for about three weeks, and I couldn’t tell anybody. …

I got a call that next day on a Sunday from Cardinal Bernardin in Rome, thanking me for accepting the appointment. And then telling me, of course you know this means you’ll have to leave the seminary. You can’t do the work of being auxiliary and still be on the seminary faculty full time. And I agreed to that.

He said that he was grateful, and he looked forward to working with me.

… He started the phone call from Rome on my personal phone number. He said, “Hello Wilton. This is Joe.” My response was, “Joe who?” Because I had never been accustomed to calling the Cardinal Archbishop by his first name.

That was one of his ways of saying that our relationship had changed, that I would be his auxiliary. He then said that on the night before, that Sunday evening, the 28th of October, he invited me and the other candidates to come to dinner at his house and then the next morning it would be announced.

I didn’t know who the other candidates were. … He told me then it was Bishop Timothy Lyne, who was the rector of the cathedral, Bishop John Vlazny, who was the rector at the college seminary, and Bishop Placido Rodriguez, who was a Claretian, who had grown up in Chicago but was then the pastor of Perth Amboy, the Claretian parish in the Diocese of Metuchen (New Jersey).

I knew Bishop Lyne and I knew Bishop Vlazny, but I didn’t know Bishop Placido Rodriguez. And so I met him … that evening at the cardinal’s residence on that Sunday before it was announced.

Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory stands outside Sacred Heart Church, Atlanta, Sept. 25 as the 2008 Red Mass prepares to get underway. Photo By Michael Alexander

Were you aware of any special qualities that you had (to become bishop)?

I didn’t know. The process had obviously been in the works for eight or nine months, and it had obviously been initiated by Cardinal Bernardin, who was asking for auxiliaries.

I know that I worked with the cardinal as an emcee for about a year.

So I had spent time with him at ceremonies, driving him around for confirmations and anniversaries and special Masses, so he had gotten to know me … and I guess saw what he thought would be some qualities that with some training, would be helpful.

How did you learn to be a bishop? Because you went from being a priest to being a bishop within 10 years.

Right. I was the minimum age. I learned it from Cardinal Bernardin. Basically… watching him with people. Watching him … encounter people. Watching him approach issues. Watching his gentleness, watching his fidelity, his approachability, his … just insight, his ability to listen and problem solve. Learning how he went about … administering a very large archdiocese. …

He was a delegator. … If I was to be his auxiliary, I had responsibilities, and I just had to step up and … get them done.

… It was a new structure in the archdiocese of Chicago that he had six auxiliary bishops, that he divided the territory and each one had a territory, a certain number of parishes and schools and hospitals. And we were to be his delegate in that territory—working with the parishes, problem solving and conflict management and representing him at public functions. It was just a wonderful 10 years of learning from him—and making mistakes and trying to figure things out. But he was always available.

I established a custom that about once every 6 or 8 weeks I would make an appointment with him, and I would draw up the agenda based on things that were going on in my vicariate that I wanted him to know about. Not to solve but to have him have the opportunity to weigh in before I did something that he didn’t want done or to give me the insight how he would solve it. And so I would come together and I’d have the agenda and maybe there would be 20 or 25 things. Just bullet points, you know. … And then I would just simply say, you know, this is going on. This is what I know. And then he’d get a chance to say well, how bad is it or what do you suggest we do? So he could just stay ahead, or he’d say, “Oh I wouldn’t do it that way. Because if you do it that way, this might happen.” And that way, he kept informed through me. He could see my vicariate through my eyes. And then he could guide me and help me, … evaluate issues. And it turned out fine.

You had to close some parishes and schools, including your own.

The first parish I had to close, as a bishop, was the parish … St. Carthage, where I had been received into the church … and I think he asked me to do that to toughen me up.

… You know, if you can do this here, and live with the pain and know the pain and know the people. … And they were calling my mother and saying, “You know, Ethel, I hear Butch (which you know is my nickname) is going to close the parish. Now he wouldn’t be doing that. And my mother said, oh don’t worry, I’ll talk to him. I had to go, Mother, you’re making things worse.

… It was clear that parishes had lost basically most of their community. They couldn’t pay their bills. The parishes, the buildings, the physical plant needed hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars of repair work. So over the 10 years that I was there, I presided at the closure, the merger, the consolidation of 33 parishes in my vicariate. My area.

But Chicago is like many of those northern dioceses that had been established by immigrant communities, you know, and the city had grown into the suburban community. So in one area—actually the area I grew up in—Inglewood, which was largely a working class community, from my childhood, had been a densely Catholic community in the 40s, in the 1940s and 50s, there were 10 parishes in a square mile.

Eight blocks by 8 blocks by 8 blocks by 8 blocks, 10 Catholic (churches)… and some of them were huge… like Visitation was a parish of almost 6,200 households. It had a high school, a grammar school, two communities of sisters, 75 nuns serving the girls school and the grammar school, and it was down to a handful of people.

And so my home parish was one of those, … St. Carthage, St. Brendan’s, Visitation, you know all of these parishes that the people had moved out. It had gone through racial change, and so the Catholic community that was so densely Catholic in this working class community had moved away, moved into the suburbs, and so the community no longer needed 10 parishes in a square mile. It was just not feasible. So that was my baptism by fire.

The other thing we found in looking at Chicago was that the number of black Catholics increased greatly in Chicago in the 1980s.

Actually, the number of black Catholics increased tremendously in the 1950s and 60s when Catholic schools received black kids who were not from Catholic families and the parents went through instruction or inquiry classes. So during the 50s, basically post-war, Chicago, and this is true in many of the Northern (cities), there were tremendous numbers of converts that came into the Catholic Church via the Catholic schools.

And it happened in Chicago, it happened in Detroit, it happened in Philadelphia, it happened in Boston, New York, … all of these cities that had Catholic schools that began to accept non-Catholics, largely, a good number of African-Americans and the evangelization that went forward through the Catholic schools.

Turning now to the role of the bishop, how would you say that it’s changed in the past 25 years?

Well, different facets of the episcopacy during the course of the history of the church have received greater or lesser emphasis. The skill set has shifted. Bishops are first of all pastors, always have been, always will be. But what dimension of the pastoral work has increased and what dimension has changed has shifted—not disappeared—shifted. I wrote my column several weeks ago on the three munus, the munus docendi, munus regendi, the munus sanctificandi. Those are the three responsibilities that every bishop in every age, in every environment, deals with. Different moments in history and in times and in circumstances may highlight one over the other. Certainly as a diocesan bishop now for 15 years, the munus regendi has changed for me because I’m now the responsible pastor. When I was in Chicago, that was Cardinal Bernardin. I was still a bishop, but he was the bishop in charge. I was helping him, assisting him, in the munus regendi. Now that falls to me and did in Belleville.

Archbishop Gregory addresses the teen track during the 2007 Eucharistic Congress at the Georgia International Convention Center. Photo by Thomas Spink/Archdiocese of Atlanta

Bishops, in the 25 years that I’ve been in this ministry, bishops have experienced some tremendous challenges—our credibility has been tremendously challenged. What I’ve experienced is a closeness to the people that I don’t think bishops had in a prior age. You know I have a pastoral council. In the image of an older generation of Catholics, the bishops were removed, they were aloof, you wouldn’t talk to them. They sometimes … lost the common touch— which is one of the great gifts and one of the attributes that I believe Cardinal Bernardin (had) …he never lost the common touch, he never lost the ability to be close to his people and to make them feel close to him.

People say, well don’t you have a driver? No. I mean, yes, I have an emcee, and a lot of times he does drive me to ceremonies, but most of the time I drive myself and like it.

And pump your own gas.

And pump my own gas! Because that’s a part of being a human being. … It is a good image to see the bishop in the store, buying tomatoes, pumping his own gas, dropping off things at the cleaners. Now I have people that help me. You know I don’t do all of those things every time. … But every once in a while it’s good to see the bishop in Target.

It’s good! Because it lets people know, you know, he lives in the same world we do. He lives, he sees the same events in life.

The happiest time that I spend as a bishop is with our kids. You know it is the happiest … because I enjoy being with young people. I enjoy their laughter and their antics … I’d be the first to say I only see them in the best of light because they’re excited about me being there, it’s a ceremony or visiting a school or something like that. So I don’t see them when they’re stinkers.

You see the complete honesty, too, don’t you?

Oh yeah, because the kids … they are guileless. … In confirmation, a lot of the questions that the kids ask me, when I give them that opportunity, are the questions that the adults would want to ask, but they’re too sophisticated. … But the kids say, “Where’d you get your hats? How old are you?” You know, and I enjoy that. It’s life giving for me.

How you think technology has influenced the role of the bishop?

You know I am not as technologically sophisticated as I’d like to be, but I am light years ahead for most of my colleagues. … I still need some of my younger priests to do things that they probably say, oh if he were so technologically sophisticated, he could do this himself. So I’m not there! I also know that with each generation, if you really need something done on your computer, you should probably ask a 15-year-old, who could do it, you know, in a New York minute.

Archbishop Gregory sits in front of his office computer at the Catholic Center in Midtown Atlanta as he awaits his next meeting of the day. Photo By Michael Alexander

I wanted to ask, briefly, about 2002, when Catholics were so shocked by … the sex abuse scandal, and it comes up, over and over again.

My entire episcopacy, if God gives me the ability to live long enough to retire and then whatever years beyond that, I will be identified as the bishop who was the chairman during this crisis moment in the church. And people say, well when will we be over (this)? … The day that they bury me, someone will write he was the one because … it was such an earth-changing moment for the church.

Do you have any pastoral letters in the works? The last one you did was on immigration.

I may be working on another letter but I have not focused it yet. As I said in my column a couple of weeks ago, I much prefer using my weekly column as the vehicle for teaching for a couple of reasons. One, it’s accessible to people, people tell me—now maybe they’re trying to flatter me. I hope not. But they read it. Why? Because it’s two pages and it’s focused on a particular issue, and … they can read it while they’re having a cup of coffee. There are certain things that need a pastoral letter—the sobriety, the solemnity, the length of a full pastoral statement. But most of the things that people encounter, they encounter in a brief moment. To be perfectly honest, in the age that we live, communication is within 90 seconds. If you can’t say it in 90 seconds, you lose your audience.

Now, there are things of significance and weight and importance that cannot be settled in a 90-second time frame. … As a bishop, there are times when I have to write a longer, more thoroughly documented, more carefully nuanced, more sophisticated vehicle for communication. But for day in and day out, my column. … I wrote about 360, 370 in Belleville, and I’m now up to about 200 here in Atlanta. So that’s about 550, 560 columns I’ve written on just about everything. Not everything, but many a thing—prayer and spirituality and justice issues and immigration and sanctity of human life, and the death penalty, and the virtues and Catholic religiosity, and all those things, so I’ve written … between 2,000 and 2,500 pages in the years.

Why did you choose to study liturgy?

I didn’t choose it—the seminary—I got a phone call from then the rector of the seminary at Mundelein, Thomas Murphy, who eventually became the bishop of Great Falls, Billings and eventually the archbishop of Seattle—Tom said that the faculty at the seminary had kind of identified me as someone they wanted to join the faculty to teach liturgy. So it wasn’t my choice, it was the seminary’s choice, my former teachers, and it was Cardinal Cody’s choice to send me.

Now when you picked your scripture for your motto, do you recall what caused you to pick that scripture?

I do. When I was a new priest in the parish in Glenview, it was one of the readings that was frequently chosen for funerals, and that passage always stuck out, so whether we live or whether we die, “we are the Lord’s.”

And that “we are the Lord’s” became something I thought about and prayed about a lot, you know, both in anticipation of funerals, because that was where it was often used, but kind of that abiding relationship that we have with the Lord. We are the Lord’s. Good times, bad times, happy moments, sad moments. It is a bond that is not broken. And as a bishop, it reminds me that my relationship with the Lord is united with the relationship that all of those people out there have. We are the Lord’s. Not just me. But all of us.

Is there anything you’d care to comment on regarding the difference between being a bishop up North say, and then being a bishop in the Bible belt?

It’s clear. We are in a growth and an expansion mode. … I’m opening parishes. … But the Catholic Church is a minority church here, whereas in most of those major Northern dioceses, the Catholic Church is the majority religion, and that means that we have to be aware that we have to live in an ecumenical context—they do, too—the majority religious community looks at ecumenism from a different vantage point than the minority participants. And so that makes me very much aware and makes all of us aware that we share the religious responsibility for this community with many other religious faiths.

Is that how you then became interested in (ecumenism)?

The new job? The new job that I got from the Catholic bishops? Again, they identified me. I didn’t seek it. There’s a nominating committee of the bishops, who come together once a year to look at the chairmanships that will be open, and they then recommend bishops to run for those open, those positions. So last year, once again, the nominating committee said we think that maybe Wilton would be a good person to head up this committee. He’s now in Atlanta, where ecumenism is a first, primary important concern. We think that his knowledge of the conference, having served as president, would be helpful. So the bishops identified me as a candidate. I didn’t go to them and say, I want to do this.

Are there any saints or holy people of the church that are a particular inspiration to you?

I remember once having the privilege of celebrating Mass for Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta. … When I was a doctoral student in Rome, I used to say Mass for Mother Teresa’s sisters. They had three different locations in Rome. … The American priests that were in town would rotate saying Mass for the sisters because the community language was English, so even if the sisters were Italian or Spanish or Portuguese or French, the language of the house was English. And I stayed in Rome during the summer of ’79 because I was … finishing my dissertation. And that meant that I was one of few American priests in town … I celebrated Mass for the sisters like maybe, rather than just once every week, … sometimes three and four times… And one day, one of the young sisters in training said, “Oh Father, tomorrow our mother is going to be here.” Well, it didn’t register with me—I thought maybe the mother of some of the young women was coming to visit. So the next day I’m vested for Mass and I say Mass and in this group of 30 young sisters, in the middle of them kneeling, was Mother Teresa. So I’m celebrating Mass for Mother Teresa. At the end of Mass she came into the sacristy, and she thanked me and she thanked the other U.S. priests for celebrating Mass for the sisters. And she said, “Father have you ever been to India?” And I said, “No Mother, but I’d love to go one day.” She said, “Would you like me to ask Cardinal Cody to release you to come to work for my sisters in India?” And I thought oooohh, you know because had I said yes, she could have called Cardinal Cody and said you have a young priest here who would like to work in India … So I said, “Mother, I think maybe one of these days I’d like to visit.” (laughing). So I remember … my encounter with a real saint. One day who literally will be a saint. … soon I suspect.

Archbishop Gregory is surrounded by his brother priests during the annual Chrism Mass at the Cathedral of Christ the King, April 2007. Photo By Michael Alexander

What newspapers do you read?

Usually each morning I usually scan about 15 different newspapers online. I’ll read, obviously I get the AJC, but I also read The New York Times, I read the Chicago Tribune, Chicago Sun-Times, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, … the Houston Chronicle, the Boston Globe, the Pittburgh Gazette, Miami Herald. I just scan them online. Because I’m a news junkie—I like to find out what’s going on in the world. I think, one of the things as bishop I’m supposed to be on top of things, you know, don’t necessarily have answers but you know I think a bishop ought to be aware of the world around him. The good, the bad, and the ugly.

One of the number one questions people ask me is how is Archbishop Gregory’s health?

Oh, I’m fine. … Actually, I was very fortunate. I knew that because my dad had had prostrate cancer about 12 or 15 years ago, I knew that it was in my genetic makeup. And so I immediately told my doctor in Belleville and here, let’s keep an eye on the PSA. And so actually, a year and a half ago, a year ago last spring, when I went in for my regular physical, my doctor said, you know, Archbishop, the PSA is at the upper range of normal—but it’s still normal—but it’s been kind of creeping up slowly, and he said, given the fact that … it’s in your hereditary makeup with your dad having had it and as an African-American, you’re in another high risk group, he said, let’s play safe. Let’s, just to be on the safe side, let’s do a biopsy. Well, it took me about three months to get an appointment because nobody is rushing to set up an emergency appointment for somebody whose PSA is still in normal range. But when I finally got it, and the results came back … I had the surgery, I had excellent, excellent, excellent … care, they caught it very early, it was in less than 10 percent, it was a less aggressive form, and I went back to work after a month. And within two months, I had already gone to Rome, within three months I was already playing golf, I play racquetball, Physically I’m as good, if not better, than I was.

I do urge men, as I wrote, and especially to our priests, monitor your health. Please, please, please, please monitor your health. It is not unmanly to do the annual physical. It is not unmanly to get enough sleep, to take a good vacation, to watch your weight … you’re not pampering yourself, you’re taking care of God’s … creation.

So, there’s nothing—I had no follow-up. I didn’t have to do anything after the surgery.

Do you have a personal goal that you’d like to share, something that doesn’t include your golf game?

(Laughing) Yeah, my golf game can only be cured by God, and he’s not been listening.

I’m enthused about the planning process and the results that it will provide us, for our future here in the archdiocese. Changes that need to be done based on the planning process here in the organizational component of the diocese, looking at the future needs in the pastoral institutions of the archdiocese. I’m very, very pleased that we’re doing it that way, and I think we’re doing it the right way so that we will lay the foundation for the wise pastoral development of this archdiocese. I’m very enthused about that.

And I’m just very happy with doing what I’m doing.

I like being the Archbishop of Atlanta. I like the community. I feel I’ve settled in well with the community. I love my priests. We have wonderful, wonderful priests. I feel very comfortable with the people that I’ve met in the archdiocese. There are some families in the archdiocese that I feel very, very close to. They are family to me. They are my people.