A tattered Irish flag in the Hibernian Benevolent Society section of Oakland Cemetery, Atlanta, is placed beside the grave of Thomas Michael Fessenden. The young man, born July 14, 1956 and died Dec. 13, 1975, was laid to rest before his 20th birthday. Photo By Michael Alexander

Atlanta

Irish Roots In Atlanta Are Deep, Historic

By ANDREW NELSON, Staff Writer | Published March 13, 2008

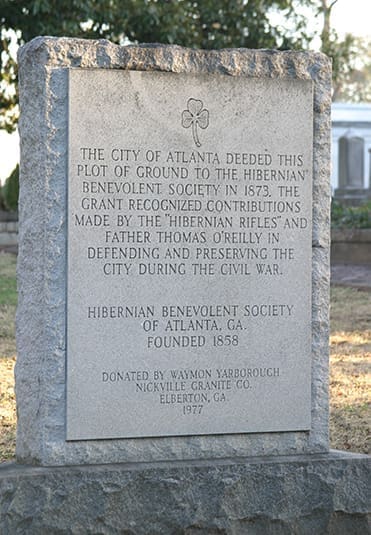

Back in 1893, James Murphy was laid to rest. His granite tombstone leans toward the west; the etching at the foot of the stone is difficult to make out. His is one of a dozen markers in this grassy plot in Oakland Cemetery. It is a special place, reserved for the Irish in gratitude for service by the community and its leaders during the Civil War, from defending the city on the battlefield to deterring Union troops from burning downtown civic and church buildings.

The downtown landmark cemetery is rich with the graves of daughters and sons of the Emerald Isle.

The St. Patrick’s Day focus is on parades, green beer and good times. But just a couple of miles away from the parade floats are the silent reminders of the native Irish in Atlanta who shaped the city in its earliest days.

Dorothy Mears, an Atlantan of Irish descent, was a member of the initial first grade class at St. Thomas More School, Decatur, and she was also a member of the first ninth-grade class at St. Pius X High School, Atlanta. Photo By Michael Alexander

“Since (the Irish) were the first immigrant group to the city and since they were assimilated so quickly into Atlanta society, they have a string of firsts,” said Dorothy Mears, a retired high school guidance counselor and historian for the Hibernian Benevolent Society.

Among the notable Irish in Oakland Cemetery are Dr. Daniel O’Keefe, a former priest and an early advocate for public education in Atlanta, who died a year before his vision was realized and Patrick Lynch, part of the well-to-do Lynch clan who traveled to Union lines to convince Union troops to preserve Atlanta civic and church buildings.

Other stories about the Irish and Atlanta are plenty. For instance, Samuel Mitchell, of Pike County, received a land deed for the sale of a horse. Instead of selling the valuable downtown land, Mitchell donated it to the state. The land is where the Georgia State Capitol and Atlanta City Hall are now.

And the history of the Irish wouldn’t be complete without someone throwing a party. The first recorded social gathering held in the city is credited to an Irish woman as she celebrated a wood floor in her shanty.

Frontier Town Attracts Irish From Urban Slums

Those early immigrants in the mid-1800s banded together to help their less fortunate countrymen with the Hibernian Benevolent Society. Part charity, party social club, it aided Irish folks struggling to land a job and find a home. The society also served as a cultural resource, keeping alive Irish heritage as many of the men married local girls and assimilated.

What was started by shopkeeper Bernard T. Lamb, this year marks 150 years since its founding. Members believe it is the oldest civic organization in the city of Atlanta. It continues to meet monthly at The Harp Irish Pub in Roswell and organizes social events like its annual ball and marches faithfully in the St. Patrick’s Day parade down Peachtree Street. It recently started a $1,500 scholarship for college students. It also supports other charities, contributing to the Visiting Nurses Association, American Cancer Society and Muscular Dystrophy Association.

The Atlanta City Council named March 17 in the city as The Hibernian Benevolent Society of Atlanta Day.

“We represent an ethnic group that has very good qualities. They laid the foundation of the city. We did some very special things,” said Mears.

Atlanta in the middle of the 19th century was frontier and a railroad hub. Irish men looking to get away from the urban slums fled New York and Boston to the frontiers of Appalachia and the Southeast. Irish men found jobs first on building the railroad and then opened grocery stores and in time white-collar businesses.

Unlike in the Northeast, where signs read “Irish Need Not Apply,” discrimination was not an obstacle in the beginning here.

“They overcame discrimination pretty easy because Atlanta was a frontier and there was so much need for labor,” said Mears.

The 1850 headcount of people in Atlanta found native Irish numbering 45, according to Mears. In 30 years, the numbers reached 422 native born. The census reported that 22 percent were proprietors and 18 percent white-collar workers, according to Mears.

At one time all five of Atlanta’s City Councilmen were Irish, according to the society’s Web page.

The Irish In Oakland

Around the same time the Irish started to show up, city leaders bought six acres on the outskirts of downtown as a public cemetery to bury the dead of the 2,500 people living here. People visiting loved ones at what was called Atlanta Graveyard found themselves in a rural garden cemetery.

When the Civil War exploded around the city, it forced the cemetery’s expansion to take in the war dead. In 1867 the cemetery reached its present 88 acres.

The cemetery mirrors the prejudices of society of the 19th and 20th centuries inside its enclosed brick wall. The dead were segregated by race and religion. The African- American burial section is on the northern end, away from whites. The Jewish section is separate from Christians.

Some 40,000 people rest here; among them are the unmarked graves of potter’s field, Confederate and Union soldiers and 24 former Atlanta mayors. Well-known Atlantans, including “Gone with the Wind” author Margaret Mitchell (Irish by the way), Maynard Jackson, the first black mayor of Atlanta, and golf great Bobby Jones—whose fans leave golf balls—are buried here.

Today, the rumble of the nearby East-West line of the MARTA trains cuts the solitude of the park.

Davant Turner has led tours of the cemetery for many years. He has near encyclopedic knowledge of the place. He once counted 20 Lynches, 99 Murphys, 106 O’ surnames and 1,600 Mc- surnames on cemetery tombstones.

He led a small group around, stopping at some of the Irish markers, including one of the most photographed markers in the whole cemetery, that of the Neal family. It is a grief-stricken mother sitting beside her daughter, who died at 22. Both hold Victorian symbols of grief, with palm leaf and laurel wreath in hand.

He talked about the plot given to the Hibernian Benevolent Society, which measures roughly 60 by 40 feet with a dozen grave markers dotting the grass.

This monument marks the Hibernian Benevolent Society plot in Oakland Cemetery, Atlanta. Photo By Michael Alexander

As the story goes, city fathers wanted to thank the Irish community for their efforts during the war years, especially efforts to stop the burning of the city.

“The Irish were just ready to step forward and protect property,” Turner said. “Many different companies went out from Atlanta (to fight in the Civil War.) But the original group of guards would be the early Hibernian Rifles,” said Turner, a longtime Hibernian.

For their efforts, the society was given this land. It has room for approximately 80 plots—roughly 20 remain. Initially it was for poor Irish, but now membership in the group ranks higher than financial situation. The bylaws don’t allow reserving a plot, so people are dissuaded from burial if they don’t know if their spouse will also be buried beside them, Turner said. The last burial appears to be in 1997 when John Wynne, a Vietnam veteran, was put to rest.

One of the largest family plots in Oakland is the Lynch family, Irish Catholic down to their DNA. The monuments look onto the towers of downtown Atlanta.

At one time the family owned much of the land where Georgia State University sits.

Betty Ann Lynch, a mother of three whose love of history made her become a volunteer guide at the cemetery, married into the Lynch family. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather, Patrick Lynch, was among the movers and do-ers of early Atlanta.

He accompanied Father Thomas O’Reilly to talk with Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to spare five churches and civic buildings from the torches that burned down the city. Their efforts spared St. Philip Episcopal Church, Central Presbyterian Church, Trinity Methodist Church and Second Baptist Church, as well as the Catholic Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. In addition, Atlanta City Hall, the Fulton County Courthouse and a residential area between Mitchell and Peters streets escaped the torches.

Patrick Lynch operated a few different rock quarries in the city, and one still exists on Northside Drive. His home in Buckhead hosted the first Catholic Mass in the city in the 1840s. His family name is preserved in a stained glass window at the Cathedral of Christ the King.

Others of the five Lynch brothers were proprietors of businesses that attracted state and city leaders.

“They came in for their hot toddies, not their coffee break, but hot toddies in the back of Lynch’s,” she said.

Lynch said people celebrating St. Patrick’s Day in Atlanta do so because of the Irish buried in Oakland Cemetery.

“In the end, when you come this many years down, it is so wonderful each little part that every individual has played that has built the foundation of this city. … Whether or not they got recognition from society, they got recognition from God, and they certainly got recognition in what’s left behind. Because if they hadn’t done what they did, it wouldn’t be there today.”