Passing the Dragon: Revisiting Flannery O’Connor’s True Country after 100 years

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published March 26, 2025

Maybe it’s Thomas Merton’s fault.

Maybe when the great Trappist monk and spiritual writer wrote his hyperbolic elegy for Flannery O’Connor—dead at age 39—in 1964, he perhaps cast this young Georgia Catholic genius in an impossible guise: “Now Flannery is dead, and I will write her name with honor … When I read Flannery, I think of someone like Sophocles. What more can be said of a writer? I write her name with honor, for all the truth and all the craft with which she shows man’s fall and his dishonor.”

Merton writes that O’Connor chronicled the decline of genuine respect, that in her cast of bizarre and blinded characters facing epiphany, she displayed the modern world’s disease of contempt: “Contempt for the child, for the stranger, for the woman, for the [Black person], for the animal, for the white man, for the farmer, for the country, for the preacher, for the city, for the world, for reality itself. Contempt, contempt, so that in the end the gestures of respect they kept making to themselves and to each other and to God became desperately obscene. But respect had to be maintained.”

O’Connor herself understood this paradox as one that could only be comprehended within the contours of what she called the artist’s “True Country”—that region that united the geographical, the linguistic and the spiritual in a universal understanding of self among others. This revelation could only be understood when both writer and audience agreed that “Mystery cannot be separated from manners in order to produce something a little more palatable to the modern temper.”

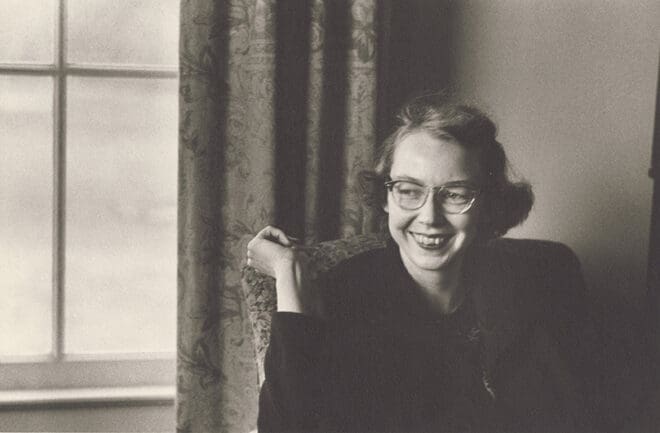

Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor is seen in an undated photo. OSV News photo/courtesy 11th Street Lot

Merton’s appraisal of O’Connor’s legacy—and Flannery’s own understanding of her purpose as an artist—are both under scrutiny as the literary world celebrates her centennial this month. I too have been deeply contemplating my own relationship with her work, a marvelous small canon of literature, correspondence, and meditation that I have read and studied and taught for more than 30 years.

To me, Flannery O’Connor is above all an outsider. She is not a primitive artist, as so many great Southern artists in multiple genres have been, for she was highly educated and well read. Yet she is an outsider, nonetheless.

Her entire life is marked by exclusion.

She grew up Irish American and Catholic in a state that openly legislated against both her ancestry and religion. She was raised in an Irish-Catholic enclave in a segregated Savannah that today, ironically, hosts the second largest St. Patrick’s Day celebration in the United States.

O’Connor’s Catholicism was a rarity in mid-20th century Georgia. The state was only about two percent Roman Catholic. Atlanta was essentially mission territory; what we know now as the Archdiocese of Atlanta did not even become a diocese until it was split from Savannah in 1956. Atlantans of my parents’ generation can recall going to the schoolyard at what is now Sacred Heart downtown to “look at the Catholics.”

As a Southerner, she was ridiculed and lampooned as backward and deficient. Before he came to recognize her genius, her own mentor at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, Professor Paul Engle, described believing she was “retarded.” Upon their first meeting, Engle asked her to write on paper everything she said, for he could not understand her middle-Georgia dialect. Even in class, he read her stories aloud for her, so that the other students could understand.

As a woman, she was forced to drop her given name Mary, fearing that no one would want to read the stories of an “Irish washerwoman.” Reviewing her first novel, “Wise Blood,” in Britain, the great Catholic novelist Evelyn Waugh wrote that “If this really is the unaided work of a young lady, it is a remarkable product.”

As a person who suffered with a debilitating and ultimately fatal disease, Lupus, she endured the indignity of crutches, public humiliation and limited access to the glamour of a mid-century renaissance in American literature that was centered in New York. O’Connor signed her first book not in a Broadway bookstore or Madison Avenue apartment, but in the library of Georgia College. Rather than mingling with Truman Capote and Harper Lee, she raised exotic birds on her family’s farm outside of Milledgeville. She wrote and watched her peacocks every day without fail, and she usually did so in pain.

Miscast at two extremes

One hundred years after her birth, she has been miscast at two extremes, either as a racist or as a saint. She was neither.

Merton was correct. O’Connor wrote about a society in which ignorance, mistrust and contempt were engrained. The segregated, post-Reconstruction South may be gone now, but to understand O’Connor’s work, the reader must reckon with that past, however unpleasant it may be.

There are O’Connor stories that I simply could not teach in a public university now. Reading back over all her work this year, I have been shocked anew at stories such as “The Displaced Person” and “Judgment Day,” in which the racist mindset of the characters is frankly sickening. The critics such as Merton who understand that O’Connor was confronting the reality of her true country might be at peace with these texts. The less informed reader is going to come away repulsed, unless they have a teacher who can show them the struggle in which O’Connor herself wrestled.

O’Connor’s work cannot be viewed outside the context of the Civil Rights Movement that developed and blossomed while she observed with caution, interest and deep empathy. Speaking as an outsider, she took an apologetic approach in explaining that “The Southerner’s social situation demands more of him than that elsewhere in the country. It requires considerable grace … and it can’t be done without a code of manners based on mutual charity. The old manners are obsolete,” and to reach a new kind of communion, “both races have to work it out the hard way.”

That “hard way” for O’Connor, as well as the great figures of the Civil Rights Movement who came before and after her death, was one in which the spiritual could not be denied. That O’Connor’s fiction was deeply situated within Catholic spirituality and orthodoxy, and the Civil Rights Movement was entrenched in a scriptural and oratorical tradition, is a crucial bond between two separate societies who had always been dependent upon the other, but who would have to incorporate love in their new relationship.

We don’t often think of love when we discuss O’Connor’s fiction, for as she knew, that language wouldn’t work for the skeptical modern reader. “When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal ways of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.” That approach makes her work difficult, but it also makes it irresistible. O’Connor’s fiction might make us uncomfortable in the 21st century, but it must be read.

O’Connor often described the parable St. Cyril taught his catechumens: “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. Beware lest he devour you. We go to the Father of Souls, but it is necessary to pass by the dragon.” She used the story to make her point that “No matter what form the dragon may take, it is of this mysterious passage past him, or into his jaws, that stories of any depth will always be concerned to tell, and this being the case, it requires considerable courage at any time, in any time, not to turn away from the storyteller.”

Merton placed O’Connor upon a pedestal. We live now in an age when pedestals are for knocking down. O’Connor knew this and essentially prophesied about it. She bemoaned both the collapse of conviction and the glorification of the sentimental.

Her work endures, however, despite society’s whims, because it is endowed with unflinching honesty and courage. By revealing flaws, faults and even evil inherent in the human condition and human experience, she opens us to the possibility for understanding and redemption. That she can also make us laugh, that she dazzles us with her powers of observation and her ear for language, is astonishing.

O’Connor once attended a literary cocktail party at which the conversation turned to religion and religious practices. One guest recalled her own departure from the church but remarked rather wistfully that she still thought of communion as a beautiful symbol. O’Connor’s immediate colloquial yet eloquent defense of the Eucharist, that “If it’s only a symbol, to hell with it,” speaks all we really need to know about the foundations that underpin her life, her work, her legacy and our own entry into the world of her true country.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of OCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.