Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Pinocchio’ is a gift for Christmas

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published December 26, 2022

The young and critical Flannery O’Connor once derided Carlo Collodi’s “Pinocchio” as “one of the worst books” she had ever read. If O’Connor were able to see the newly released Guillermo del Toro adaptation of the archetypal story, she might change her mind. The stop-motion animated feature is a masterwork and along with Walt Disney’s 1940 film is perhaps the greatest cinematic adaptation of “Pinocchio” ever made.

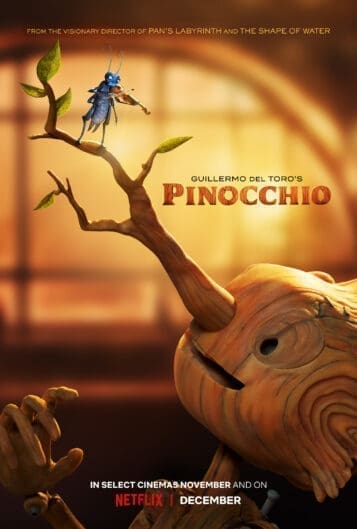

The film was in development in one form or another for about 15 years. Recently completed, it opened in select theaters in November and went into wide release via Netflix on Dec. 9. While the film is definitely del Toro’s unique vision, he shares directing credits with Mark Gustafson.

Image from Netflix

And the 2002 illustrations of Gris Grimley were as much an influence on del Toro as Mussino’s pictures were to Walt Disney. The look of Pinocchio is as important as the narrative, and del Toro and Gustafson have created a striking and original visual representation.

Del Toro has wanted to make the film all his life, ever since he saw the Disney adaptation when he was a boy. “Pinocchio is my passion,” del Toro has said. “No art form has influenced my life and work more than animation, and no single character in history has had as deep of a personal connection to me as Pinocchio.”

The film also clearly reveals del Toro’s complex feelings about his Catholicism and his native Mexico. At the same time, the context of the film allows for sharp criticism of war and tyranny that makes del Toro’s version remarkably relevant to our own times. By taking the story out of a fairy tale setting and placing it in World War I and the rise of fascism in Italy, del Toro lends a new lesson to a tale steeped in moral allegory.

A perfect pinecone

Unlike many versions of the story, the carpenter Geppetto in del Toro’s film already has a son, his beloved Carlo. They live in a small Italian village, where Geppetto is working on a commissioned crucifix for the parish priest; the piece is installed behind the main altar, and Geppetto is putting the finishing touches on it. One fateful day, while at work in the church, war planes drop a bomb in the village. Geppetto is able to escape the church, but Carlo is killed.

Geppetto buries his son along with a pinecone, a perfect pinecone, that Carlo had found. As years pass, Gepetto becomes a drunken inconsolable man. The pinecone, however, blossoms into a tree. Gepetto cuts down the tree, and from it crafts a new son, a boy made of wood, who is christened Pinocchio by a wood sprite.

As in most versions of the story, Pinocchio is rowdy and full of mischief. He burns off his own feet. He gets in trouble at school. He is gullible and foolish. He joins a malevolent circus master named Count Volpe, who is a blend of the story’s familiar fox and cat, in servitude. And, of course, he learns about honesty and what happens to his nose when he lies.

There are other variations from the typical structure that make the film more compelling. Most of the film takes place in Mussolini’s fascist pre-World War II Italy. The film is strongly anti-dictator and anti-war; it is a perfect commentary upon the current madness in Ukraine. Pleasure Island becomes instead a military training camp for boys. Mussolini replaces the Coachman, and the dictator is lampooned as a baby.

Yet the most important departure from the familiar plotline is that Pinocchio does not yearn to be a “real” boy made of flesh and blood, nor does he need to. Del Toro has asserted that realness should come from one’s heart, one’s potential for goodness, and not from superficial appearances. In this Pinocchio, a wooden puppet can have as much heart as a human being. This deeper theme takes the story out of the simple morality fable that O’Connor hated and places it on a far more interesting level.

For one thing, from the beginning the film demonstrates its awareness that the story has always been a product of Catholic Italy. The opening of the film is full of Catholic atmosphere: prayers, the church, the priest, the crucifix—there is a reverential and gentle sense of grace in the presence of the ordinary. Then, too, there is the ominous awareness of evil—the warplanes—lurking in the background. As you will see, though I won’t spoil this subplot for you, there are questions about mortality and immortality, death and resurrection.

The death of Carlo is tragic indeed. Gepetto’s sorrow and anger at the loss of his innocent child becomes our own rage at the futility and stupidity of war waged upon the guiltless and helpless.

At the same time, however, the film suggests the importance of suffering and how we grow from it. One essential component of the story has always been the talking cricket who represents the work’s conscience. For Disney, it was the singing Jiminy, but for del Toro, it becomes the woeful Sebastian J. Cricket—brilliantly voiced by Ewan McGregor—who like his namesake endures all sorts of suffering on his way to enlightenment. The cricket still remains a comic foil, but the fact that he too has a lesson to learn makes him more interesting.

Other familiar characters from the story are also rendered in fresh ways, including the Blue Fairy—almost always implied as the Blessed Virgin Mary—who isn’t the beautiful blonde of the Disney version, but a character linked more to mythology. Lampwick becomes Candlewick, and while he’s still a bully, he becomes an anti-war pacifist. And Pinocchio isn’t cute; in fact, he’s ugly. Yet ugly is not unholy. Watching this more grotesque Pinocchio, I thought again of O’Connor and her wonderful essay “An Introduction to a Memoir of Mary Ann.”

In short, del Toro takes a story that has always peddled easy morality lessons such as honesty and obedience and transforms it into a reflection upon mystery, sacrifice, redemption and profound love.

Becoming whole

For this reason, I can’t imagine the film using any other approach besides stop-motion animation. The movie is a fine example of the aesthetic principle of “form follows function.” Stop-motion animation is tedious and time-consuming; it is hard work. While del Toro uses technology to aid him, a good deal of the puppetry is mechanical and done by hand (the making-of featurette is fascinating). This painstaking method equates with the themes of making and becoming whole that are at the center of the story.

As in all versions of the story, del Toro’s Pinocchio learns many lessons, but perhaps the most important is the mystery of sacrificial love. My favorite part in the film occurs when the wooden Pinocchio rails at the crucifix: “He’s made of wood! Why do they like him?” As Pinocchio will discover, selflessness guided by love is the secret. And the crucifix is after all only a representation that leads us to a deeper awareness of the real.

Del Toro intuitively understands the great paradox of Christ’s passion, that the beaten, humiliated and crucified Christ becomes the object of adoration. The victim becomes the victor. Had del Toro not used Geppetto’s crucifix as a device in the film, the movie would not have achieved the overall effect that it does.

I’ve been careful not to reveal too many of the film’s surprises, but trust me that if you are a fan of del Toro’s work, and you have an affinity for the archetypal Pinocchio story, you are in for a wonderful fresh approach to an old tale.

Yet I must share the most fitting line from the film for Christmas: “He became a real boy to save you.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.