Harriet Monroe, Joyce Kilmer and Poetry Magazine

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published April 29, 2022

This April—National Poetry Month, as I remind you almost every year—I am lobbying hard for the return of my Poetry Magazine 75th anniversary poster to its rightful place in our home. I have a long and complicated history with my poster, and I want it back where I can see it every day.

In 1990, when I began graduate studies in the Department of English at Georgia State University, I first saw the Poetry poster in the lobby of the department office. It was a beautiful poster, illustrated by the famous New Yorker artist Edward Koren, and I was immediately struck by it. I wanted one of my own. I contacted Poetry Magazine. “Sorry,” they said, “we don’t have any available for sale.”

I confess that in a fit of madness (graduate English studies can indeed drive one insane) I contemplated simply taking the poster off the wall under cover of darkness and keeping it for myself. Of course, I didn’t resort to theft, but I must say I was tempted.

Years went by. I was a resident in the GSU English Department for 11 years. In 2001, shortly after my marriage and right before my doctoral commencement ceremony, I decided that I was at last worthy of some of the trappings of middle-class success, such as magazine subscriptions, and I became a subscriber of The New Yorker, America and Poetry Magazines.

The New Yorker and America arrived first, and they never stopped coming. They came every week. They lay around the apartment in great piles, a testament to my good taste and education, if not to my sense of time management.

The arrival of Poetry took a while longer, which is fitting for a magazine of verse. When at last it came, I was delighted, though not as thrilled as I was by what arrived a few days later. I came home from teaching one afternoon to discover a cardboard tube leaning against our apartment door. The tube was addressed to me and postmarked from Poetry Magazine in Chicago. Inside the tube was the Edward Koren poster I had so long coveted. A simple postcard stated something to the effect of “In gratitude for your recent subscription to Poetry, please accept this 75th anniversary poster as our gift.”

I had the poster framed, and it hung in our apartment and then in our first son’s nursery. My son shall be great indeed, I thought. The poster hung in his nursery and bedroom in two different residences. When he was about four years old, he declared that the creatures on the poster terrified him, and always had, so the poster went to my campus office, where it hangs crookedly by the door, a reminder of innocent days when I was a lowly graduate student.

Consecrated to art

Poetry Magazine is 110 years old this year, which makes my poster 35. It is one of the most successful periodicals in history and is certainly a small miracle in the world of literary magazines.

The magazine was founded in Chicago, in 1912, by Harriet Monroe. Monroe was a Chicago native, and while she was not a Catholic, she was educated at Visitation Academy of Georgetown in Washington, D.C. Today the school is known as the Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School, and it is the oldest Catholic school for girls in the original 13 American Colonies.

I believe that Monroe’s Catholic education helped shape her worldview not only of people, but also of art; indeed, she said that she had “consecrated” herself to art. Monroe started Poetry by convincing a consortium of Chicago businessmen to fund the venture with relatively expensive long-term subscriptions. She edited the magazine for nearly a quarter of a century, until her death in 1926 at age 75.

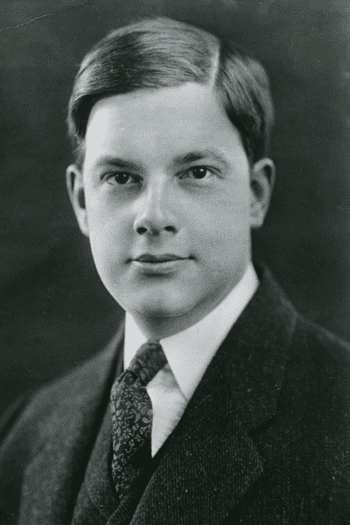

Catholic poet Joyce Kilmer was killed in 1918 in World War I during the Second Battle of the Marne. Photo

Courtesy Columbia University, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Monroe’s outlook toward art was inclusive and ecumenical. The official policy of the magazine, she stated, was thus: “The Open Door will be the policy of this magazine—may the great poet we are looking for never find it shut.” Again, I believe her Catholic education convinced her that like the church, art evolves through time; it is changing even as it remains changeless. And among all the arts, Monroe believed poetry best exemplified the virtues of beauty, truth and goodness.

Though Monroe embraced the tenets of high Modernism, particularly Ezra Pound’s motto to “Make it New,” she also remained open to convention and tradition, as long as the work exemplified quality. At Pound’s insistence, she published T.S. Eliot’s landmark “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” in 1915, and she made audiences aware of poets who became fixtures in modern literature, including Carl Sandburg, Wallace Stevens, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) and William Carlos Williams. Giving new, unknown voices a chance to be heard has always been a hallmark of the magazine, even though it has published some of the finest and most famous writers in the world. It is not an exaggeration to say that publication in Poetry is a prerequisite for a great poet’s reputation.

A beloved Catholic poet

Of all the outstanding work that the magazine has published for over a century, many people are surprised—perhaps even shocked—that the most popular poem in the magazine’s history is Joyce Kilmer’s often parodied “Trees.” You know it, even if you think you don’t: it begins, “I think that I shall never see/A poem lovely as a tree,” and concludes a few lines later “Poems are made by fools like me,/But only God can make a tree.”

Kilmer’s “Trees” was the first poem he published in Poetry, in the August 1913 issue. He was paid $6 for it, and Monroe resisted the urge to edit it, even though Kilmer gave her permission to cut some lines. Pound thought the poem was the best piece in the magazine.

“Trees” appeared shortly after Kilmer and his wife converted to Catholicism. His conversion occurred when his daughter was diagnosed with polio. Kilmer was already a Christian, but in addition to the comfort he found in Catholic liturgy and prayer, he also deeply admired the church’s position on ethics and aesthetics. Kilmer’s appreciation of the connection between art and morality, between beauty and tradition, are hallmarks of the great Anglo-American Catholic Literary Revival of the 20th century.

Kilmer became one of the most recognized and celebrated poets in America; he was certainly the country’s most successful and beloved Catholic poet. Monroe had a deep respect for Kilmer’s art and life. She admired his poetry, and she respected his religion; at a time when anti-Catholic sentiment was still strong in America, Monroe’s own experience with Catholicism allowed her to empathize with Kilmer’s devout faith. Through her publication of Kilmer, she enriched an intellectual and even avant garde audience’s understanding of the church.

Consider, for example, this short Kilmer verse “Easter” that Monroe was so fond of: “The air is like a butterfly/With frail blue wings./The happy earth looks at the sky/And sings.”

Poetry published several more poems and essays by Kilmer until he volunteered for military service in World War I. Sadly, Kilmer was killed in the First World War, in July during the Second Battle of the Marne in 1918. He had volunteered to lead a dangerous expedition and was most likely killed by sniper fire.

Today, Kilmer’s achievement is remembered more in popular culture than in the academy. Anthologies of American literature as well as the Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry do not include him. Kilmer is, however, memorialized in several public spaces, many of them military sites, and I suspect “Trees” will be read—and parodied—for the rest of time. My favorite reference to Kilmer is in the Catholic novelist Jon Hassler’s novel Staggerford, in which a hilarious episode affirms Kilmer’s relevance while mocking passing fads.

Monroe paid tribute to Kilmer’s art and courage in an eloquent elegy published in the October 1918 issue. You can read her tribute, as well as several of Kilmer’s other poems, at the marvelous Poetry Foundation website, which archives and preserves the legacy of this most important cultural treasure.

But they still don’t sell posters.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.